Why do Saint Paul's neighborhoods of color have a disproportionate number of vacant properties?

Story published: July 2,2020

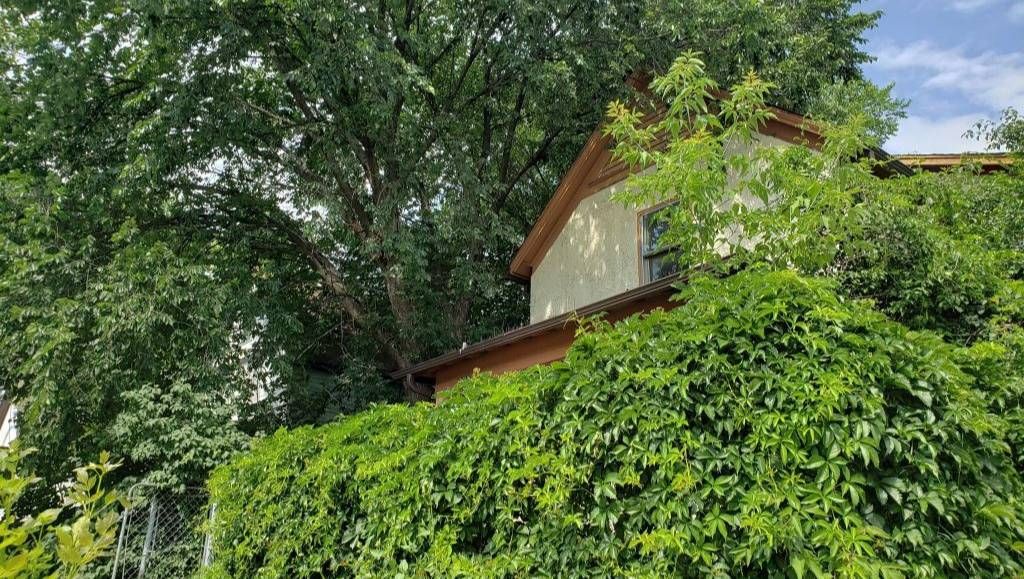

The vacant building next to Patricia Letourneau's home has become an eyesore. People lived in the building when it caught fire 10 years ago - but when another fire struck the house as recently as two years ago, the City of Saint Paul deemed it a vacant property. The landlord has worked to fix the building, but the yard is overgrown - and Letorneau suspects that work to fix the building is being done for cheap.

“They’re not replacing the floors that are warped from the water … They didn’t even replace the wood inside the walls from the fire,” Letourneau said. “We try hard to keep everything nice outside and keep it looking really good, and then you look over there now and their grass is all full of weeds … they had dandelions up to my hips.”

With its canopies of overgrown foliage, the house in the Payne-Phalen neighborhood of Saint Paul represents just one of many vacant properties across the city that officials have worked for years to rehabilitate. But a Twin Cities PBS analysis found that more than half of all vacant buildings are located in neighborhoods where people of color make up the majority of residents - and dilapidated buildings can bring disastrous consequences when it comes to residents’ health, property values and crime.

A Lot Has Changed

Things were different when Letourneau moved into the Payne-Phalen neighborhood 30 years ago. Many residents owned their homes, and she said they took care of the community. Nowadays, most people rent homes instead, and violence is a growing concern.

“Last year there was a guy shot right at the corner there,” Letourneau said, pointing to a street intersection 70 yards from her porch. “By the time [police] got here, he was dead. It was really sad - he had five or seven kids.”

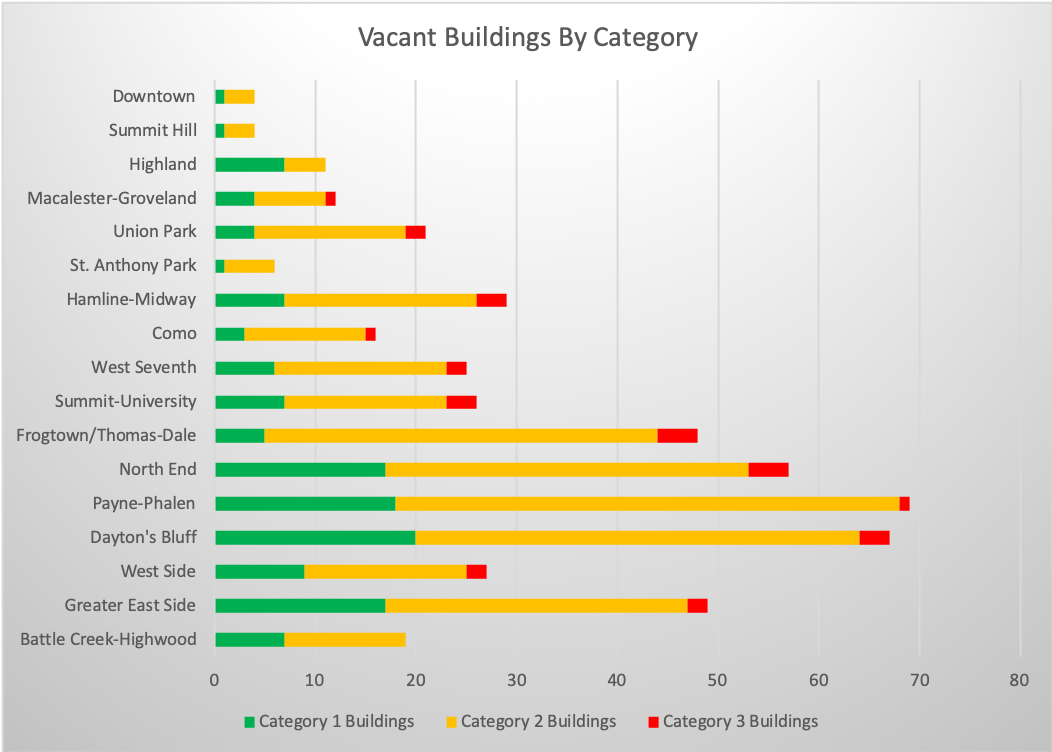

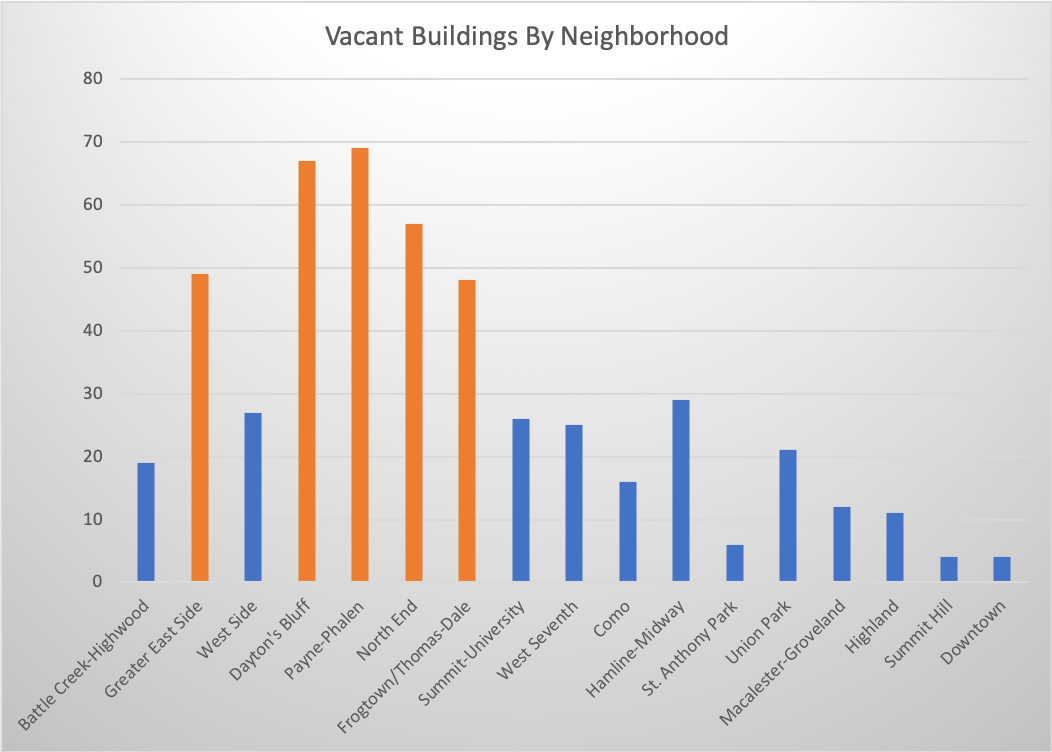

A 2014 study by the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that vacant and abandoned buildings are linked to increased crime rates and public-health risks, and can decrease one's quality of life. Though neighborhoods where people of color are the majority comprise just over a quarter of Saint Paul’s districts, 59% of all vacant and abandoned properties are concentrated in those neighborhoods. Half of the city’s worst vacant properties, which are considered a safety threat to communities and to people who might enter them, are also in those neighborhoods.

*Map of registered vacant and abandoned houses in Saint Paul. Neighborhoods / districts colored orange are those where people of color, according to data by Minnesota Compass, comprise more than half of the area's population.

According to Columbia University Chair of Epidemiology Charles Branas, that is by design. Branas has studied vacant and abandoned properties for years, finding that they are associated with heightened levels of stress, depression and gun violence. He said that the disparate vacant and abandoned housing stock in Saint Paul mirrors national trends, and is explained by the redlining and racist housing policies that restricted people of color.

“Where the redline maps are, and the redlined areas for many cities in the U.S., is where you’re going to find all this vacancy and abandonment,” Branas said. “That needs to be dealt with because it’s unseating people’s quality of life on a daily basis.”

City officials know that this is an issue, but say that funding and awareness present major obstacles to addressing it.

Along with other urban centers across the country, the Twin Cities have a history of racially discriminatory housing covenants that prevented people of color from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. That history ripples in the present-day affordable housing crisis: By limiting opportunities for home ownership, people of color were stripped of one key way to build equity over time. Discover more in “Mapping the Roots of Housing Disparities in Minneapolis.”

“Or else we’re going to fail”

When asked why vacant and abandoned properties are concentrated in neighborhoods of color, Luis Pereira, the Planning Director for Saint Paul’s Department of Planning and Economic Development, cites three factors: the 2010 foreclosure crisis, community disinvestment and institutional racism.

The department has worked for years to prevent people from vacating properties and has succeeded in reporting fewer such properties now than there were a decade ago. But Pereira said resources are tight, and many residents don’t know about city services that could help to prevent vacancies. He said that they need help and input from the community to make a change.

“For us to be successful as city planners and community-based planners, we have to do those things or else we’re going to fail,” Pereira said. “If we could only multiply staffers [in communications] by 10, I would suspect every single district council and every single block would know about these great programs we have.”

Pereira expects that his department’s 2040 Comprehensive Plan, which suggests ways to address poverty and vacant properties, will be finalized by this fall. In the meantime, Saint Paul’s Department for Safety & Inspections is preparing for a potential boom in the number of vacant buildings as a result of and economic fallout from the coronavirus and damage from protests for the police killing of George Floyd.

George Floyd’s police killing has inspired countless artists across the globe to create murals in his honor, works that also call for justice and anti-racism reform. And that’s left a lot of people wondering what will happen to the works of art – many created on temporary surfaces such as plywood panels – when communities start to rebuild. Students and professors at the University of Minnesota have created an online database that aims to catalog these expressions so they can be studied for years to come.

George Floyd’s police killing has brought together communities in a show of resilience – but it’s also revealed deep-seated racial inequities in access to healthy food now that the Lake Street area, where many grocery stores were damaged or destroyed, has become a food desert. Almanac reporter Kyeland Jackson examines how that lack of food access is actually rooted in racism-charged issues related to access to jobs and opportunities to build wealth.

In 2019, Taylor Kueng (who identifies as gender non-binary) witnessed the arrest of two Black men in downtown Minneapolis. Taylor and their friend filmed the incident until they were both also arrested by police. One year later, a different video implicated their brother, former officer Alex Kueng, in the police killing of George Floyd. Discover how one family has been impacted by two different videos that captured police force.