Who made Minnesota the Gopher State?

An amateur artist at the center of EVERYTHING.

What if we told you…

…that one little-known person is at the center of Minnesota's moniker as the Gopher State, the Great Seal of Minnesota, the story about an enslaved Minnesotan-turned-Dakota warrior, and even the Science Museum of Minnesota? And what if you haven't even heard of him? Wonder if he doesn't even have a Wikipedia entry, even though Minnesota's identity has literally been shaped by his hand? Literally. Let's meet him, and some other larger-than-life characters with whom his life and work entwined.

The Gopher State

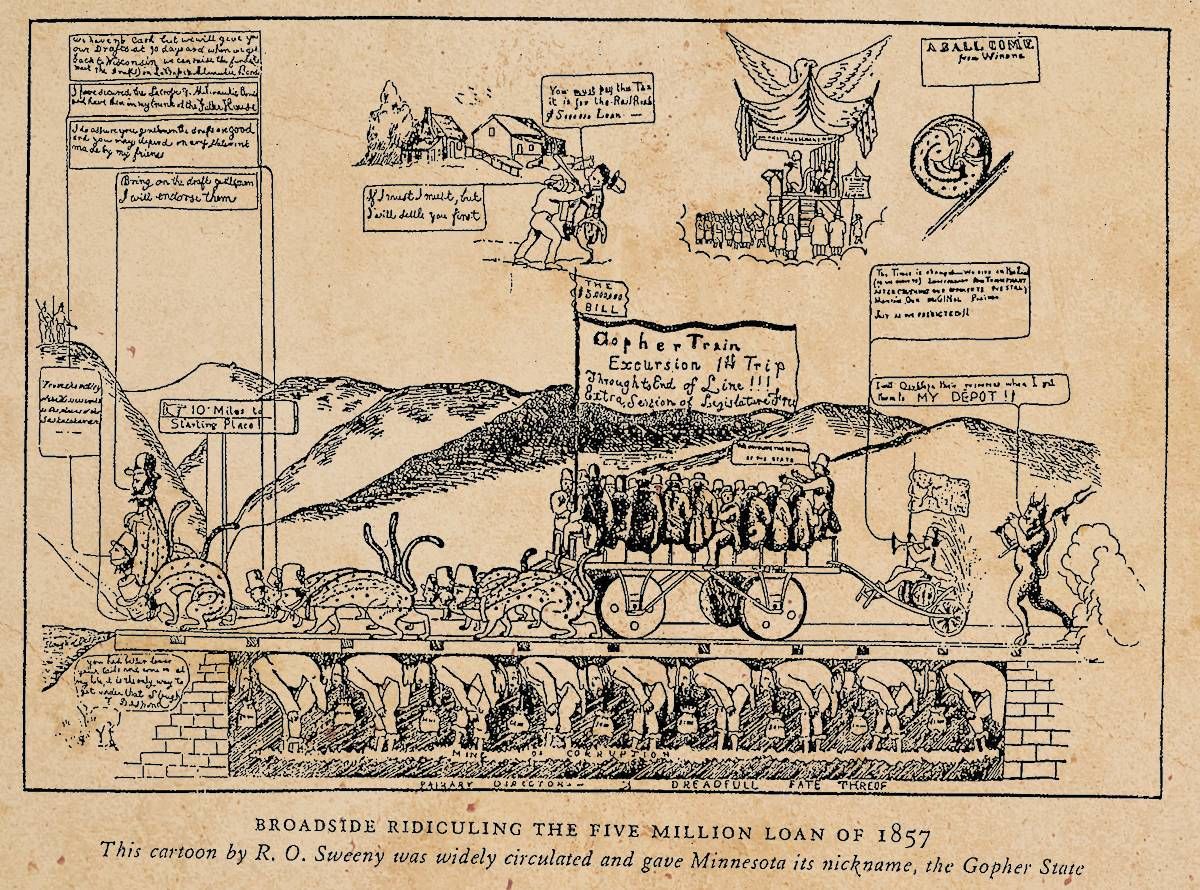

In 1857, on the cusp of statehood, a fledgling Minnesota legislature wrestled with a bill authorizing a $5,000,000 loan to railroad companies to build tracks through the soon-to-be-state. It's the kind of bill Minnesotans still love to hate: using taxpayer dollars to subsidize wealthy industrialists. Opposed to the measure was one Robert Ormsby Sweeny, a Saint Paulite by way of Philadelphia with many and varying interests, drawing among them. Sweeny concocted a complex political cartoon in response, the social impact of which long outlived its political moment.

Sweeny's rather bizarre scene features a horned devil, allegations of corruption, and a train car pulled by a team of thirteen-lined ground squirrels with human heads and top hats. The nine subterranean figures supporting the railroad bridge represent the nine lawmakers who were apparently bribed to vote for the bill; the weights around their necks pulling them down represent the bribe money ($10,000 in gold each). The nine "gophers" pulling the car represent either railroad tycoons themselves, or various proponents of the controversial legislation. It's a strange scene, especially with Sweeny's tiny handwriting and so little context into all the possible symbolism of the day.

Despite wide circulation of Sweeny's cartoon, the bill passed in a landslide. But the cartoon - despite its sudden political irrelevance - would somehow ultimately lead to Minnesota's unofficial moniker as the Gopher State. And with it, your Minnesota Golden Gophers. Ski-U-Mah!

Fun fact: It appears that it was Sweeny, himself, who conflated gophers with thirteen-lined ground squirrels. Real gophers are uglier, so we'll take it.

The Great Seal of Minnesota

But that's not the end of Robert O. Sweeny's influence on Minnesota's identity, once again on the cusp of statehood. According to Minnesota's newly-minted constitution, a Great Seal was a legal requirement for conducting state business, and it was a detail that nearly slipped through the cracks in that frenetic liminal time.

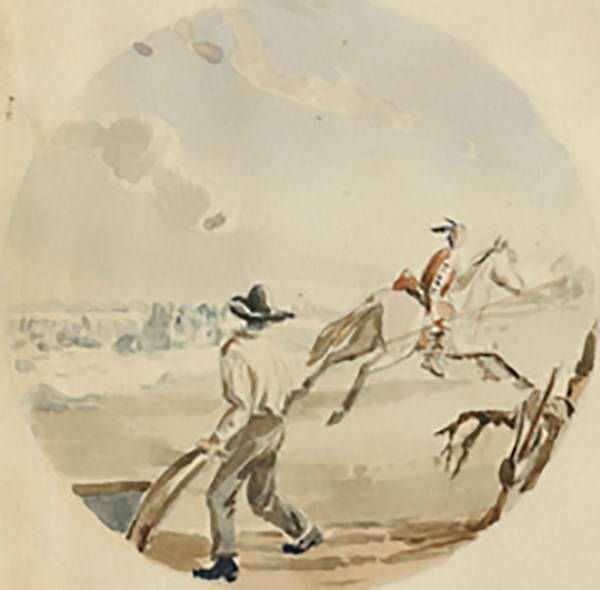

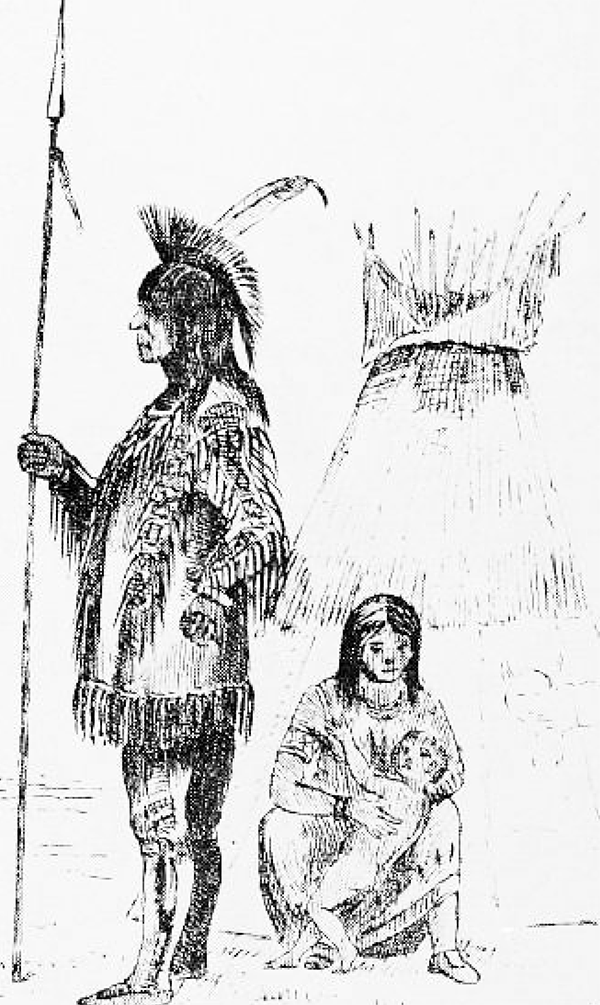

Almost a decade earlier, Seth Eastman - Army captain, gifted artist and abysmal family man - had painted a watercolor of a scene originally sketched by Col. J.J. Albert. Eastman's painting, commissioned by Territorial governors Alexander Ramsey and Henry Sibley, became the basis of Minnesota Territory's Great Seal in 1849.

On its own, Eastman's painting seems quite harmless. But once the intended symbolisms are applied, it's an appalling scene in modern context: In the foreground, a white colonizing settler is breaking virgin Minnesota soil with his plow (symbolizing the white man's right to the land because he would finally make it agriculturally productive), while in the background an Indigenous man is riding his horse into the literal sunset, looking back at the settler (symbolizing the end of Native civilization in Minnesota and the ascendancy of white people and manifest destiny). Behind the settler is a tree stump with the settler's axe embedded in it (symbolizing the white man's mastery over the wilderness and the centrality of the timber industry to Minnesota's economy). Leaning against the stump, the white man's rifle and power horn are at the ready (symbolizing the white man's martial dominance over Indigenous people and animals). The Falls of St. Anthony flow powerfully in the background (perhaps foreshadowing the water-powered milling industry that would soon define the economy).

Yikes.

In case Eastman's white supremacy message wasn't clear enough through art, his white wife, Mary, (not his first Dakota wife, Wakan Inajin-win, whom he abandoned when she was only 17 after the birth of their daughter, Winona) wrote this alarmingly blunt poem to accompany the seal design:

Give way, give way, young warrior,

Thou and thy steed give way;

Rest not, though lingers on the hills

The red sun’s parting ray.

The rock bluff and prairie land

The white man claims them now,

The symbols of his course are here,

The rifle, axe, and plough.

—Mary Henderson Eastman

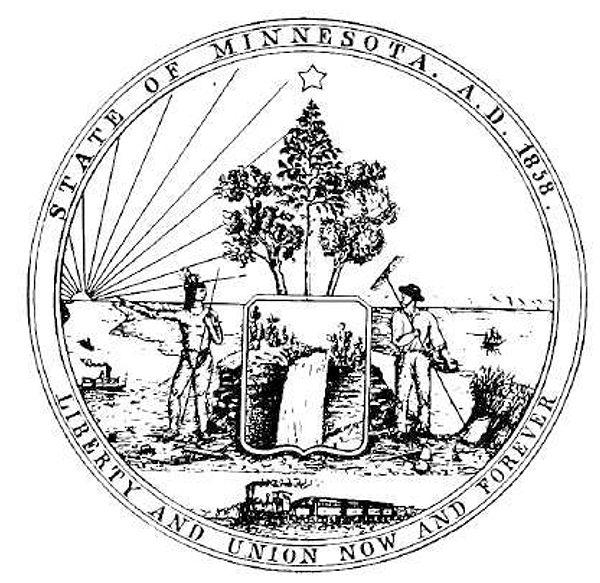

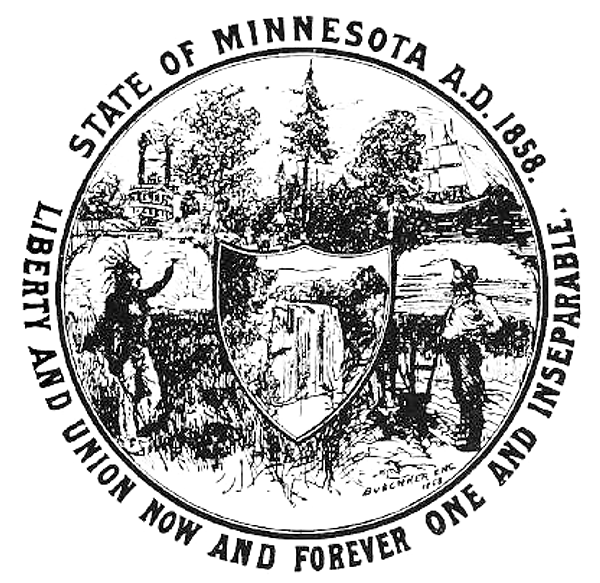

Back to 1857: With Minnesota's statehood nearly a reality and a constitutional requirement for a Great Seal, a hurried effort was put forth to create a new expression worthy of Minnesota's new status. New designs were commissioned (apparently with instructions to incorporate some of Eastman's symbols). Noteworthy contributions were submitted by Saint Paul engraver Louis Buechner - and the one-and-only Robert O. Sweeny.

The Buechner and Sweeny designs have a lot in common: Native and settler stand opposite each other seemingly as equals, with the Indigenous man pointing vaguely (perhaps hinting at his withdrawal, but certainly not in the dramatic mounted retreat of Eastman's design), trees and other natural landscape features, and Minnehaha Falls within a shield at the center of the seal. Either is vastly less problematic than Eastman's through modern eyes.

In January 1858, a Senate committee put forth Sweeny's design for adoption as the new Great Seal, which earned the approval of both the House and Senate in June. However, for reasons lost to history, the bill never became law. Instead, a last-minute joint resolution (Joint Resolution #2, if you're curious) authorized Governor Sibley to have the Great Seal engraved with Sweeny's design.

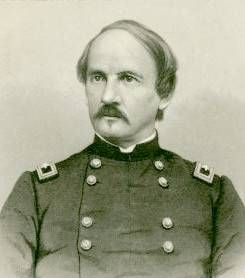

Sibley, in total contravention of all of this policymaking, unilaterally (and secretly) chose to just use Eastman's racially-charged Territorial Great Seal design, with some tweaks. Sibley had, of course, commissioned Eastman's rendition a decade earlier. As the one largely responsible for making it the territorial Great Seal, apparently Sibley wasn't ready to part with it. So the governor secretly hired an engraver to create the official Great Seal with his changes, without notifying or involving other lawmakers.

In fact, news of Sibley's secret seal engraver only broke when the engraver, himself, used the high-profile commission in a newspaper advertisement later that summer. Complaints exploded over the matter from all corners. The legality of Sibley's actions was challenged by lawmakers, to the point that Attorney General Gordon E. Cole stepped in to attest to Sibley's authority in the matter. After protracted public argument about Sibley's act of circumvention, the matter was finally settled through legislation in 1861 and signed by Governor Ramsey.

In 1989, Grant Moos wrote for Minnesota Monthly magazine:

"There is evidence that the state seal, upon which the flag is based, is somewhat illegitimate. The bill written to establish the seal was never signed by the governor in 1858, although it was given official sanction three years later. The legislature had approved a completely different design, one of Indians and whites living in harmony – a concept that then-Governor Henry Sibley felt was untenable. Sibley has been accused by historians of 'mislaying' the design that lawmakers approved and replacing it with the territorial seal he helped design. To this day Sibley's seal remains the basic design."

The Albert/Eastman/Sibley design remains the Great Seal of Minnesota - and our state flag - to this day. Sweeny's design, loudly chosen by Minnesota's elected leaders in both houses of Congress, faded into history. But in recent years, there have been many calls, proposals and efforts to redesign the seal and flag to better represent Minnesota.

Fun fact: In 1881, a fire in the capitol saw important records hauled out with haste. In the chaos, the official seal went missing. It was discovered in England and returned in 1901.

Enter Joseph Godfrey

But again, that's not the end of Sweeny's influence on how Minnesota understands itself. Sweeny's artistic skills may have resulted in the only contemporary depiction of one of Minnesota's most fascinating and reviled…people. The word "citizen" can't be accurately used, as Joseph Godfrey was born into slavery around 1830 right here in Mendota, Minn., son of an enslaved African-American woman named Courtney and a French-Canadian voyageur. Courtney was brought to Fort Snelling by an Army officer as a slave, and then sold to another voyageur, Alexis Bailly. When Joseph was five years old, Bailly sold his mother in the closest slave market, which was St. Louis. While young Joseph remained a slave, his mother successfully won her freedom through a Missouri lawyer, who would eventually represent Dred Scott.

Godfrey's continued enslavement in Minnesota took a noteworthy turn when he was hired out as an aide to Henry Sibley before his career turned to politics.

That's right: Future governor Henry Sibley employed a slave. Let that sink in.

Following years of mistreatment and misery, Godfrey's encounter with an abolitionist missionary prompted him to flee his bondage and find freedom in the late 1840s. He ran to the Dakota people, who welcomed him as one of their own with their shared trauma from white colonization and brutality. After the signing of the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux instigated by perennial malefactor Alexander Ramsey, Godfrey moved with his Dakota community to the Lower Sioux Agency, married a Dakota woman in 1857 and lived as a member of the community for years. However, over those next few years, the U.S. government's failure to pay treaty-required annuity payments on time resulted in widespread starvation and hardship among the Dakota people.

The outbreak of the U.S.–Dakota War right in his backyard at Lower Sioux in August of 1862 presented Godfrey with a choice: Fight with the Dakota and defend his family or seek refuge with the U.S. Army, whose officers had owned him and his mother as property. With regular U.S. Army troops off battling the Confederacy (Minnesota was the first state to tender troops for the Civil War), Governor Alexander Ramsey thrust Godfrey's former boss, Henry Hastings Sibley, into a military role for which he had no training: leading the volunteer infantry (i.e. angry white settlers looking for revenge) against the Dakota. For Godfrey, it was an easy choice.

Godfrey became a symbol for both sides. Sibley later accused Godfrey of active involvement in Dakota attacks on settlers. Indeed, the Dakota named him "Atokte" meaning "Slayer of Many." Yet Godfrey himself denied having ever killed anyone. In truth, there are only conflicting reports on the nature of his involvement.

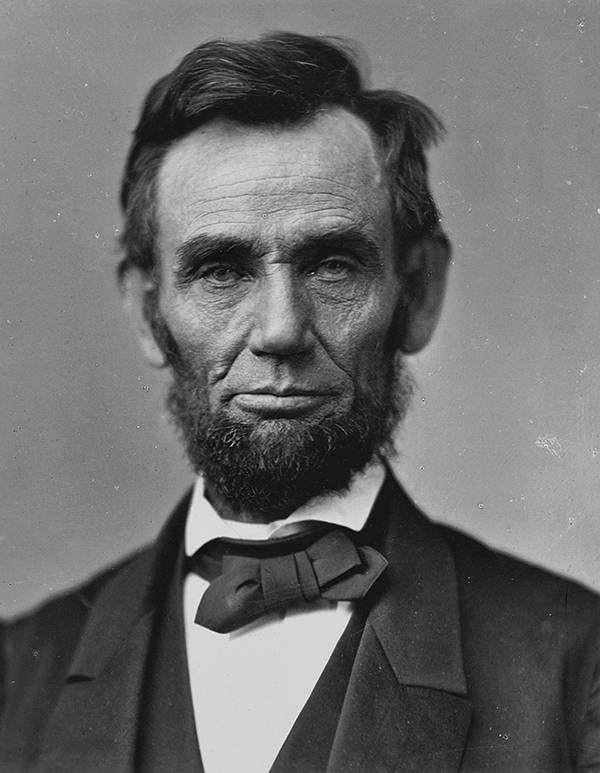

The war was bloody but brief. Six weeks later, Godfrey and a thousand Dakota surrendered to U.S. forces. Days later, he was the first combatant to be tried by a kangaroo military court military commission created by - you guessed it - Sibley. The trials were appallingly deficient, conducted by Sibley's volunteer infantry of angry white settlers. Some trials lasted mere minutes (there were 42 trials conducted in a single day), none involved defense attorneys and nothing was explained to the defendants. The whole process had no court or military oversight, only a direct channel to President Abraham Lincoln. Four hundred Dakota (plus Godfrey) were tried in little over a month. More than 300 were found guilty and sentenced to execution. Pleas to Lincoln for clemency ultimately brought that number down to 39.

In an attempt to save himself from the gallows, Godfrey testified against 11 of the 38 Dakota fighters. Although Godfrey was not convicted of murder, Sibley wanted him dead for his treachery, and he was sentenced to death by hanging anyway. But because of his cooperation, a recommendation on his behalf was sent to Lincoln, who personally commuted Godfrey's sentence to 10 years in prison prior to the date of execution.

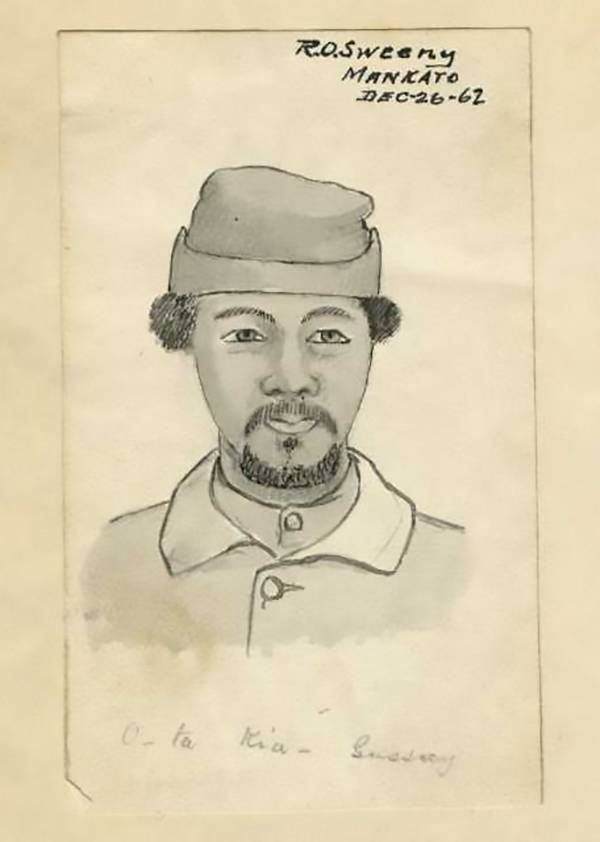

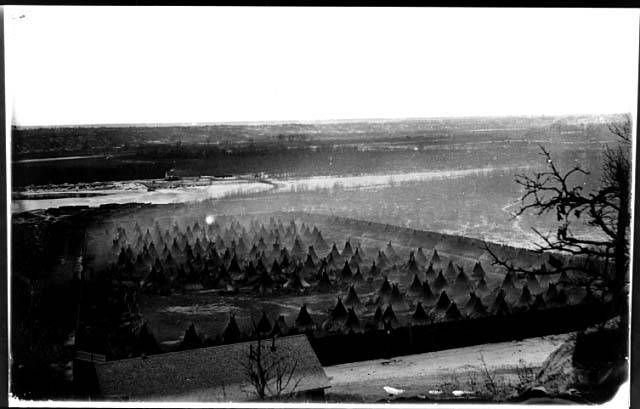

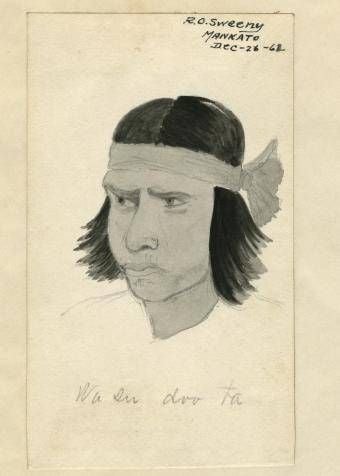

On December 26, 1862, The United States of America publicly executed 38 Dakota warriors in Mankato. That very same day, Robert O. Sweeny sketched a picture of Joseph Godfrey, which may be our only extant contemporary depiction of him. White Minnesotans regarded Godfrey as a rebellious slave, armed enemy and traitor to the United States. The Dakota - suffering the largest legal mass execution in U.S. history and soon to be completely exiled from the boundaries of Minnesota by federal edict - saw Godfrey's testimony as nothing short of betrayal.

Only three years into the sentence, President Lincoln issued a full pardon to Godfrey, who spent the rest of his life on the Santee Reservation in Nebraska, where many of the exiled Dakota from Minnesota had relocated to survive. He lived until 1909.

Godfrey's story is now seen in a very different light. We are horrified by the once-commonplace presence of human enslavement within our borders, including by men who are namesakes of counties, streets, schools. We are enraged by how the federal government and white Minnesotans brutalized the Indigenous people of this land - through violence and deprivation, but also through enacting and perpetuating a Great Seal that continues to write them out of their own homeland.

Sweeny must have been there in person for the mass execution in Mankato. He sketched many of the condemned men and recorded their names. His sketches are all dated "Dec 26 - 62."

Not-so-fun fact: Both Sibley and Eastman married Dakota women, got them pregnant and abandoned them.

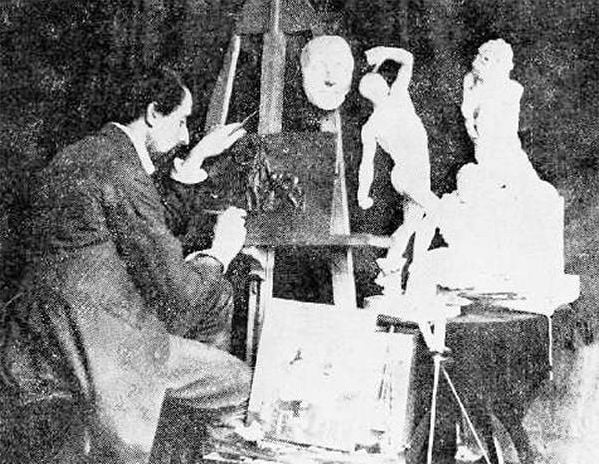

Robert O. Sweeny: Minnesota's Unknown Renaissance Man

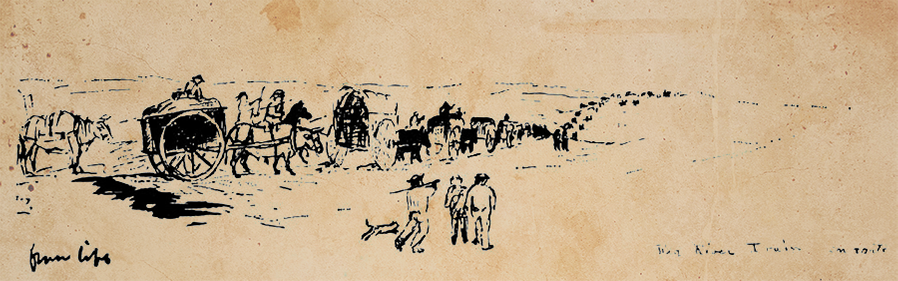

Sweeny purportedly spoke both Dakota and Ojibwe, and created remarkable sketches of Minnesota's Indigenous life at the time. Of course, he sketched settler life as well, scenes of ox carts, town life and other common frontier experiences. A lifelong Quaker, Sweeny abhorred violence, yet he traveled extensively to document the Civil War in sketches and photographs, following troops through Missouri, Arkansas and beyond. Many of his Civil War sketches are in the Missouri Historical Society collections.

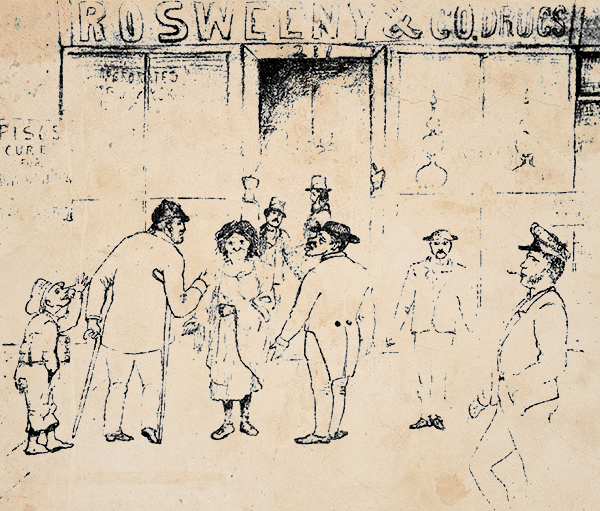

Sweeny, who seems to have always had his pencil in one hand, was really busy with the other hand. He founded the St. Paul Academy of Natural Sciences, the forerunner of our modern Science Museum of Minnesota. He served in senior roles with the Minnesota Historical Society for more than three decades. Sweeny was an active outdoorsman and conservationist, and served as the first Commissioner of Fisheries, and later as president when it was reorganized as the Game and Fish Commission of Minnesota. Oh, and he had a real job on top of all of this: Sweeny was a druggist (we'd probably say pharmacist these days). He helped create the Minnesota Pharmaceutical Association, served as its secretary for years and became known as "the father of the State Pharmacy Law" thanks to his efforts in drafting said legislation. He moved his family to Duluth and lived until 1902.

This author certainly cannot speak to the nature of Sweeny's character beyond what's been recorded. He seems to have been genuinely interested in the human experience, especially those oppressed by unjust forces. He clearly understood the power of images and symbols to make meaning and shape perception in perpetuity. He valued the natural and cultural landscapes of his time, and the wellbeing of people and the natural world of his place. He championed the ability of science to reveal life's mysteries. Those seem like admirable qualities for a man of his tumultuous time and place.

Compare those qualities to some of his contemporaries, say, slave-keeping Henry Sibley or murderous Alexander Ramsey?

Sweeny seems pretty alright.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.