What does food insecurity mean in Minnesota?

Hunger takes many forms in Minnesota: Parents skip meals so their children can eat, they water down milk so there's enough to go around or they make soup out of ketchup packets.

But when it comes to how we talk about the lack of steady access to fresh, healthy foods, buzz words abound - food deserts, food swamps, food access. While language evolves to capture the many factors that can impact a family’s ability to eat well on their own terms, one thing is certain: Language matters.

“Food insecurity deals with a lack of access to nutrition, and I also believe that access is something that we all need,” says Taronda Richardson of Appetite For Change, a social enterprise in North Minneapolis that uses food as a tool to build health, wealth and social change. “It’s not a privilege to have access to food.”

Food insecurity can also mean that families who want to purchase fresh produce and proteins are limited by a lack of grocery stores or healthy restaurants in their communities, which limits both choice and access.

“I would say ‘food access’ rather than ‘food security,’” says Jadea Washington of Appetite For Change. While Washington acknowledges that those two terms can mean very different things, she recognizes the importance of defining what you want your eating habits to be for yourself as a solid starting point. “Food access” also gets closer to encompassing the many ways that systemic racism and divestment from neighborhoods limit families who would purchase different foods if they were available.

Listening to communities, learning about their needs and investment could all help build sustainable change at a systems-level, which Adair Mosley of Pillsbury United Communities sees as the solution.

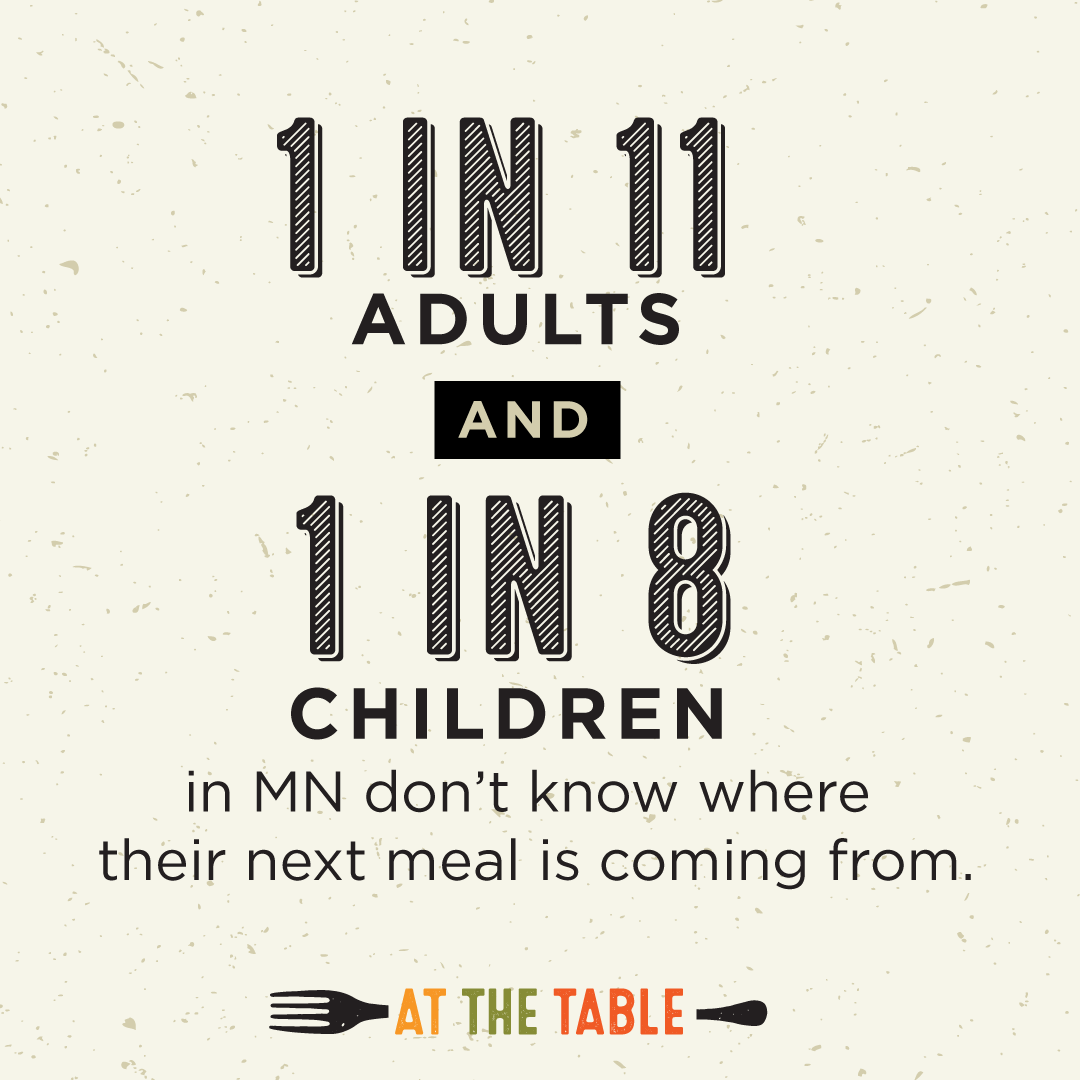

And for the roughly one in 11 adults, and one in eight children experiencing food insecurity in Minnesota, dignity and choice matter even more than language. (During the COVID-19 pandemic, it's worth noting that one in eight adults and one in five children experienced food insecurity due to job losses and ensuing financial hardships.)

DIGNITY AND CHOICE MATTER

Taronda Richardson is the Youth Training and Opportunities Program (YTOP) Manager at Appetite For Change. Every day, she helps youth gain leadership, organizational and advocacy skills using the kitchen, garden and even a music studio as a classroom.

“We think about dignity and food and the way we have to kind of carefully navigate those conversations,” she says. “So just last week, someone presented to me an opportunity to have our youth of our YTOP program receive some deliveries of fresh produce weekly. I actually brought this to our weekly Zoom conversation and I was kind of surprised.”

Instead of the enthusiasm she had expected, almost everyone on the call was silent. Richardson wondered why the group reaction had been so strong and unenthused. But having worked with teens for years, she quickly realized that the response may have been more positive in a one-on-one setting rather than as a group discussion.

“Regarding youth and young people, I think the way we approach food – and again, remembering dignity – always do it in a way that they can receive it is really, really important. That’s what I learned that day.”

RACE AND PLACE

While anyone can experience food insecurity, Black and Brown communities experience it at much greater rates than white communities in Minnesota.

“We can’t talk about food insecurity if we don’t intersect both place and race as part of that conversation, and certainly more Black and Brown communities are food insecure,” says Mosley. “In addition, our rural areas are also experiencing, disproportionally, some kind of impact around food access.”

North Minneapolis, for example, was once referred to as a “food dessert” – a phrase sometimes used to describe communities that lack grocery stores, farmers markets and other businesses that sell fresh produce.

And as Jadea Washington reminds us, the language we use can amplify or minimize the entire food access conversation.

“'Food desert' is another big buzz word, and people are talking about that a lot, but the metaphor kind of minimizes the whole space,” says Washington. “Race and class and our systemic history in the United States impacts how we access and think about and see food in our neighborhoods.”

This story is part of the Twin Cities PBS original series At The Table, which examines social and systemic issues within our food environment. Funding provided by the Cargill Foundation.

Wondering what kind of good work is unfolding to tackle food justice across the country? Check out the efforts led by these three change-makers who seek out ways to promote ancestral connection and spirituality through agricultural projects.

George Floyd’s police killing has brought together communities in a show of resilience – but it’s also revealed deep-seated racial inequities in access to healthy food now that the Lake Street area, where many grocery stores were damaged or destroyed, has become a food desert. Almanac reporter Kyeland Jackson examines how that lack of food access is actually rooted in racism-charged issues related to access to jobs and opportunities to build wealth.