Trial & Tribulation: How do juries work - and work against Black and Brown People?

As jury selection began in the murder trial of former MPD officer Derek Chauvin in early March, Minnesotans - and others around the world - got an inside look at how implicit and explicit forms of bias work against people of color as prospective jury members. Starting with the question, "Who is in the pool and who is left out?", a slew of obstacles stand in front of Black and Brown Minnesotans, and many of those are rooted in longstanding issues like voter suppression. After all, you get in the pool by having voter registration or by your driver's license registration - which is another historical barrier to entry considering the fear many Black and Brown people feel about getting stopped and frisked while behind the wheel. And if you've been in prison? You can all but forget about it.

While the Batson vs. Kentucky Supreme Court decision in 1986 made it illegal to strike prospective jurors based on the color of their skin, the present-day "voir dire" (or "speak the truth") approach to questioning jurors leaves little doubt that racism has found a different way to poison the criminal justice system. In the Chauvin trial, for example, jury members have been asked, "What do you think about Black Lives Matter?", a question that allows the defense an immediate cause to strike jurors.

In this episode of Trial & Tribulation: Racism and Justice in Minnesota, we consider the question: How do juries work - and work against Black people?

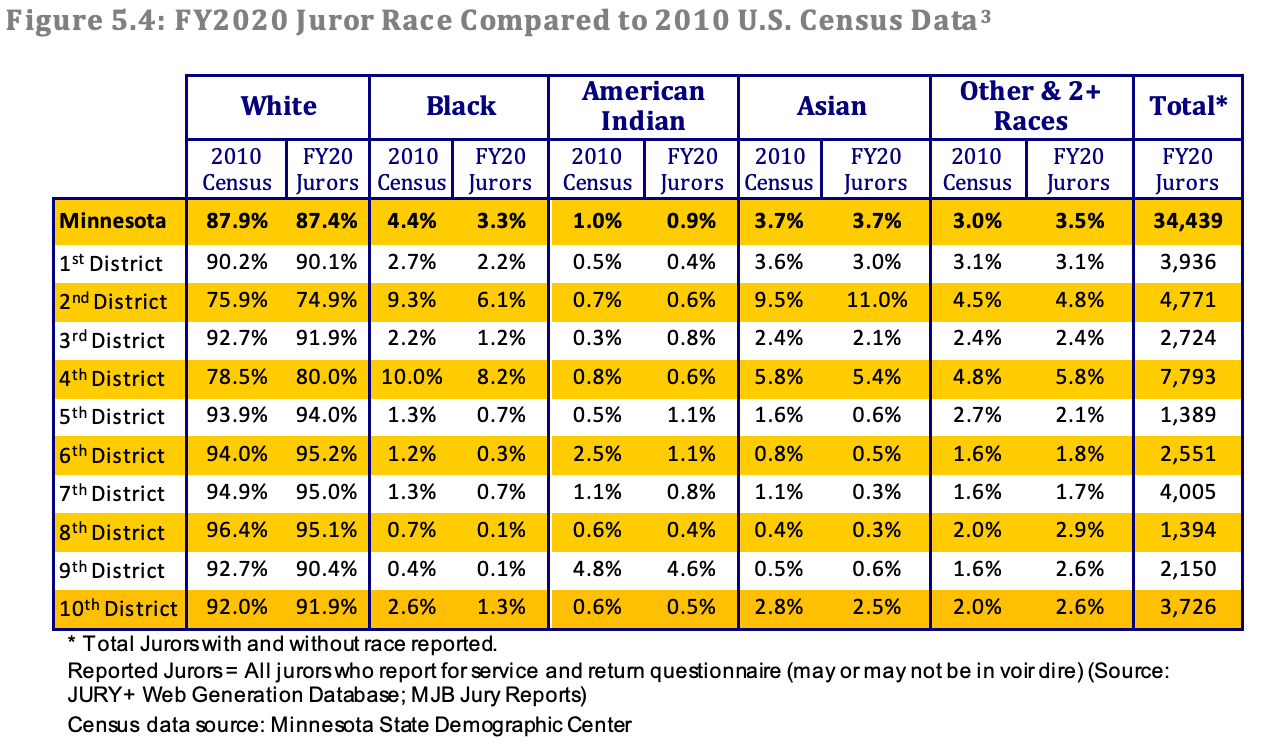

In researching the episode, we also discovered some startling data: According to a 2020 report created by the MN Judicial Branch, 87% of jurors have been white, while only 3% identify as Black.

If you're interested in raising your voice against the implicit and explicit forms of racial bias in the jury system, then consider contacting your local jury office (there's one in every county).

READ THE TRANSCRIPT OF THE VIDEO

Vivian Jenkins Nelsen, Jury Reform Task Force Participant:

The juror system is where the racist stuff goes down.

Jason Sole, Abolitionist & Criminal Justice Educator:

Don't get me started like on that jury stuff.

Otis Zanders, CEO Ujamaa Place:

Most Black people are very wary of jury and the jury selection process.

Resmaa Menakem, Racialized Trauma Therapist:

Law-abiding Black people do not get called to get on a jury.

Dr. Artika Tyner, Attorney & Law Professor:

How can we have racial justice when I'm the only person of color in this room?

Kyeland Jackson, Host & Reporter:

Hey y'all. Newsfeeds are blowing up over jury selection for the trial of Derek Chauvin. The world's watching the Hennepin County courthouse where attorneys from both sides fight for jurors to sell their case to. For a lot of white Minnesotans, juries can be inconvenient, yet fair and impartial. But for Black and Brown people like you and me, a jury is more complex than that, shaped by a long history of racism, exclusion, and bias. So here's the question. How does the jury system work and how does it work against us?

Dr. Artika Tyner:

Well, with the jury and any trial, you have a promise from the sixth amendment to have, you know, a speedy and a public trial by an impartial jury of your peers, is what we oftentimes frame it as. So when we think about juries and what's their function and role, I think they play a significant role based upon our history, the foundational tenants of our constitution, of having the opportunity to have your peers help to, in that fair and balanced principles of impartiality, look at the facts and help to determine the final, the final determination in a particular case. So how does that relate to race and looking at it through a racial justice lens in particular? Oftentimes the challenge is two-fold: the jury pool and the jury selection process. That jury pool, that initial invitation to activate that civic duty, is based upon the records of me either being registered to vote, based upon my driver's license records or my state ID.

Otis Zanders:

And both of those issues are problematic or they're barriers for a lot of Black people. And you look at the historical depth that we've gone through with this country to do voter suppression. And even today, as we are looking at states around the union revisit voter repression, trying to eliminate people's ability. And so right away, when you think about that pool that we are selected from, and that's where they sell driver's license renewal, that's another historical barrier in the communities of color, even to the extreme of people don't want to drive because of the habitual nature of being stopped and frisked.

Resmaa Menakem:

My wife just said to me two days ago she said, "I've been born and raised on the North side of Minneapolis and my ass ain't never been asked to be on a jury. I'm 56 years old and I ain't never been asked to be on a jury." How does that even happen?

Otis Zanders:

I mean, I've been a registered voter since 1972 and I'm yet to be called.

Dr. Artika Tyner:

I mean, I can think of examples in my immediate family, but I also can think about the fact that they're probably uniquely situated in the sense of yours truly.

Vivian Jenkins Nelsen:

I've been called. But wouldn't you know, after all of this, I was sick and couldn't go. So I was just beside myself.

Kyeland Jackson:

And let's not forget the new Jim Crow in America: the mass incarceration of people of color.

Dr. Artika Tyner:

Now, if we get it and take it a step further and take in account mass incarceration, another challenge starts to emerge as well. People of color are not going to be in the voting pool and that registration at the same rate because of not having the ability to have access to the ballot box if you're on any terms of probation or parole in Minnesota, but in other states, it could be a lifetime ban simply for being a felon.

Jason Sole:

I mean, I will probably never serve on a jury. You know what I mean? Like ever in my life. When you convicted or been, you know, taken through the criminal punishment system, you're not eligible to be a juror. And, you know, I think it just shows that even jury selection is rooted in bias.

Dr. Artika Tyner:

If we are saying representation matters, if we're saying equal justice under the law, we have to make sure that that jury pool represents the true landscape of Minnesota.

Kyeland Jackson:

And that's just to get called for jury service. Getting to serve on a jury is a whole other thing. Attorneys use an interrogation process called "voir dire" to expose hidden biases in each juror. And just as reading tests excluded us from voting, voir dire is used to exclude us from serving on juries.

Vivian Jenkins Nelsen:

I had never heard of voir dire. So this was a real enlightenment for me, because it's the key way that Black people were kept off of juries. Lawyers can ask you questions to see whether or not you are gonna be biased toward their client and if you should be struck for cause. And what would happen is Black people would come up, when they did come up, if the defendant was a Black person and you came up you would get struck off just because you were Black.

Dr. Artika Tyner:

Who experiences some of those preemptive challenges? Who's struck early and never gets a chance to participate? And thinking about the Batson case and ensuring that people are not simply being struck because of the color of their skin. And that they're not being limited with access to actually serve once they make it through that small pool up to the next step of jury selection.

Kyeland Jackson:

Batson versus Kentucky was a huge Supreme Court decision that made it illegal to strike jurors because of their race. It's been the law of the land since the 1980s, and it's improved the rate at which people like us can serve as jurors, but the system found other ways to make racism work today. Using questions like, "What do you think about Black Lives Matter?"

Vivian Jenkins Nelsen:

Voir dire is where the racist stuff goes down. I mean, it's there, that's it. I mean, that's the beginning of it. It's whether you even get to participate in the process. the questions that are asked to you can be embarrassing and stuff like, "Do you have any police relatives?" And then they could get struck if they did. Or, "Have you ever had a disagreement with a police officer?" And then you can get struck. You know, so, and that's, most of us, a lot of us.

Otis Zanders:

I have to talked to other people about some of their experiences and most people that do have been weeded out during the interview process.

Resmaa Menakem:

I got interviewed, but I was too, you probably can tell by my voice that they wasn't gonna choose me to be .

"Sir, you are being excused from this jury."

As soon as I started talking, they was like, "Nah, we gonna take Malcolm X off. Give Malcolm X his Quran and let him keep moving."

Kyeland Jackson:

If we didn't laugh, we'd cry, right? And beyond those biased jury pools and jury selection systems, there's our mistrust that Minnesotans of color will be not judged by a jury of our peers.

Otis Zanders:

I mean, the premise behind a jury is have a group of people that, of your peers, and I think it's hard for, talk to any Black American, to feel that, that you really represent them, or that they see themselves.

Jason Sole:

If I want a jury of my peers, you know, it's like I know who my peers are, and if I go in a courtroom and it's a bunch of middle aged white folks, man, a lot of them are not my peers. A peer means you should be able to understand the context in which things happen in my community.

Vivian Jenkins Nelsen:

I couldn't imagine what it would be like to be, as would be likely to happen in Minnesota, to be the only person of color, only Black person, and the defendant is a Black person. And, you know, to hear all of the kind of discussion that might fly about Black people.

Resmaa Menakem:

This is structural. Every institution participates in white body supremacy

Vivian Jenkins Nelsen:

The fact that we're one of the last large countries to use a juror system like we have says something.

Dr. Artika Tyner:

Before we can get to the jury pool, jury selection, I would like to see some early engagement with everyone, but in particular communities of color, on why jury service is a critical part of the pursuit of justice and how we play a key leadership role.

KyelandJackson:

These systems are biased against us, but it doesn't have to stay that way. Call your local jury office or councilperson if you've got something to say. Make your voice be heard. That's a right that's guaranteed to every citizen, no matter what the color of their skin. Until next time, Peace and love.

Resmaa Menakem:

Most of the time Black people are not, don't get called for jury. Law-abiding Black people do not get called to get on jury. That's a problem with the algorithm, right? I want to see the algorithm. I want it, I want somebody, I want some Black people, and some Brown people and some Indigenous people and some Asian people, I want them to look at the algorithm and start to begin to tweak this damn thing.

Special Thanks: Resmaa Menakem, Vivian Jenkins Nelsen, Jason Sole, Dr. Artika Tyner, Otis Zanders

Production Team: Jess Bellville, Kevin Dragseth, Danae Hudson, Kyeland Jackson

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by grants from the Otto Bremer Trust and HealthPartners.

As the trial of Derek Chauvin begins on March 8, 2021, communities of culture are going to experience that burning, suffocating feeling of trauma all over again. In the first episode of the weekly series, Trial & Tribulation: Racism and Justice in Minnesota, we talked to trauma expert, therapist and author of My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, Resmaa Menakem about how people can cope right here, right now, as the trial stirs up old and new wounds.

Data Reporter Kyeland Jackson left Louisville, Ky., Minnesota shortly after George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police. In “Tethered: How Race and Policing Binds Minneapolis to Louisville,” he hones in on the racism-fueled policing disparities that led to both Floyd’s and Breonna Taylor’s deaths.

In some measures, the “Star of the North” is failing communities of color. Rates of inequity in Minnesota fall below national standards and show how historical divides have created ongoing consequences for people with darker skin. When you examine the data, how does Minnesota compare to the rest of the nation when it comes to racial equity?