The answer may have been "Blowin in the Wind." But it wasn't easy to find.

Music helped conjure memories of home during the Vietnam War - but it never erased the hard memories.

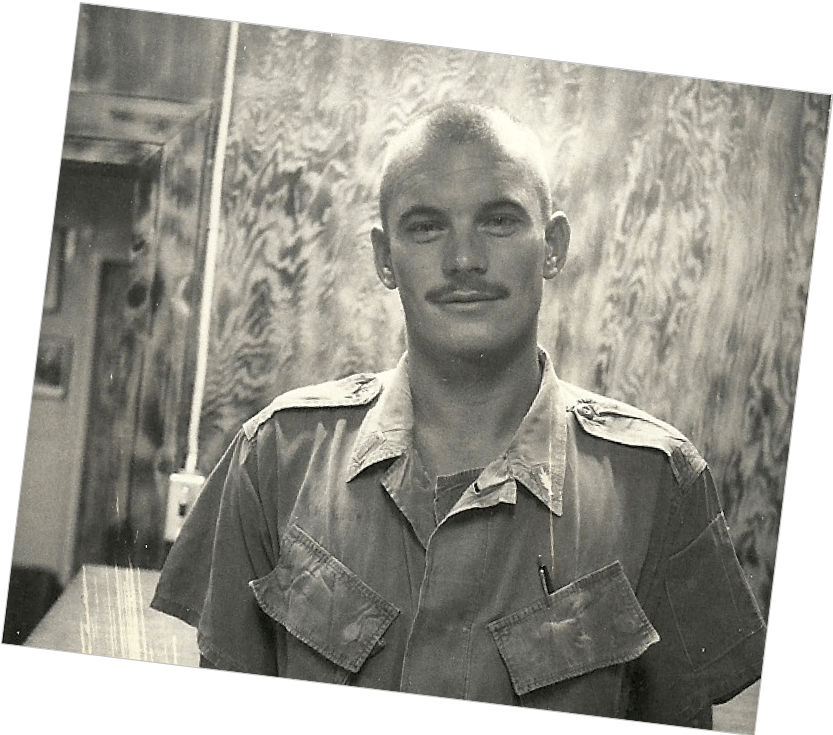

St. Croix Falls, Wis., resident Jim Bodoh describes himself as “just a good ole country boy,” whose background in farming, hunting and fishing could have placed him anywhere in the Midwest. A retired nurse anesthetist with the St. Croix Regional Medical Center, Jim worked regularly with hospitals in Minnesota and Iowa, as well as in Wisconsin. Respect for his patients was at the core of his medical philosophy, a lesson he learned in a war zone of all places.

“My experience in a field hospital in Vietnam taught me self-reliance,” Bodoh admits. “I learned to respect my patients, but not to fear them.”

There was plenty of fear to go around in Vietnam in 1968 and 1969, but Bodoh and his fellow CRNAs (Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists) at the Naval Support Activity Hospital at Da Nang were too busy to comprehend any imminent danger.

“I wore a steel helmet and flak jacket most of the time,” Bodoh recalls. “Usually an anesthetist has 500 cases in a year - I had more than 1,200. One time, after logging 40 straight hours, I fell off the stool and passed out from exhaustion.”

Fatigued, frazzled and stretched to the limit, Bodoh found consolation, and occasional comfort, in music.

“I came from the country, so that was my music,” he recollects. “As a little boy, I used to dance at barn dances and polka parties with my grandma. My favorites growing up were Jim Reeves, Hank Williams, Marty Robbins, Roy Orbison… But my all-time favorite is Buddy Holly. ‘Rave On’ is the best song ever.”

Bodoh was so starved for the music of his childhood - and unhappy with the Armed Forces Radio playlists - that he made his own reel-to-reel tapes with the songs he loved on them. “I still listen to the tapes I played in Vietnam.”

Pretty good guess that when he listens to songs like “Blue Bayou” by Roy Orbison and “Am I Losing You” by Jim Reeves or “Cool Water” by Marty Robbins, Jim Bodoh is back in Vietnam, a place he thought he’d maybe be able to avoid. Especially when he hears “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive” by Hank Williams.

“In 1966, for the first time in U.S. history, the Selective Service System issued a special draft call for 900 male nurses for the Army and Navy Nurse Corps,” says Bodoh. “I knew that, come graduation as an anesthetist, my ass would be in the service.” Still, nothing could have prepared him for what he saw at Da Nang in 1968 and 1969.

“It was right after the Tet Offensive. Casualties were immense. We had 10 operating rooms and we worked around the clock. It was just one long, never-ending triage,” he pauses. “I’m not sure how we kept it together - the instinct to survive is so great… You do whatever it takes. It was what I had to do, and that’s what I concentrated on doing.”

Bodoh did that as well as anyone, and undoubtedly that harrowing experience in Vietnam helped him to be an outstanding anesthetist with the St. Croix Regional Medical Center for more than three decades. He received the Alice Magaw Outstanding Clinical Practitioner Award from the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists in 2004.

But it was his year in Vietnam that taught him the fragility of life - and the significance of music.

“In October 1968, several Navy officers arrived at our base to observe the treatment of a triple-amputee Marine,” Bodoh’s voice lowers. “We were wondering why all the fuss, but then it turned out the Marine was Lewis Puller, Jr., the son of General “Chesty” Puller, the most decorated Marine in the history of the Marine Corps. It was a big deal.

“He was a mess,” Bodoh continues. "But like so many of the men we treated, Lewis Puller, Jr. survived, even though he jokingly told us he’d already prepared his speech for the day he’d arrive at heaven’s gate and present himself to Saint Peter: ‘One more Vietnam veteran reporting, sir. I have already served my time in hell.’”

Bodoh chokes up when he remembers the rest of the Puller story.

“He went to law school, married, raised a family, ran for office. He wrote an autobiography he entitled Fortunate Son after the Creedence Clearwater Revival song. The book won a Pulitzer. He called me years after Vietnam to thank me. I could tell something was wrong He committed suicide in 1994.”

Bodoh’s voice trails off and, in the silence, you can almost hear something - a song - out there in the wind.

“If there is one song that makes me think of Vietnam, it’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ by Peter, Paul, and Mary,” he declares. “I remember hearing it before I went, hearing it in ‘Nam, and listening to it today. It still gets to me. It reminds me of Vietnam… Vietnam was like that, just blowin’ in the wind. The song reminds me just what a bullshit deal Vietnam was.”

Jim Bodoh survived Vietnam. More than anyone, he knows that the answer to the question "How many deaths will it take?" is “too many people have died.” As his wife, Vicki, points out: “Jim likes to say that, after Vietnam, when he wakes up in the morning and knows he is alive, every day is a good day.”

This story is part of the collection The Call to Serve: Stories of Sacrifice, War and the Way Home, which was funded by the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation.

Writer Doug Bradley is both a Vietnam War veteran and also considers himself "part of the Woodstock generation." In "Caught in the Devil's Bargain," he draws parallels between the war and the concert in an effort to show that "like so much about the 1960s, the Woodstock-Vietnam dialectic is a lot more nuanced, much more convoluted… A touch of grey if you will."

As a nurse, Donna Korf was thrown into the fires of medical trauma when she was sent to Vietnam. One of her most valuable lessons? "'You didn't cry in front of patients.' Not during the Vietnam War."