Tales of a Complicated Road

Highway 61 offers splendid views – and a sticky history.

Tales of the Road: Highway 61 is a rollicking journey along the east coast of Minnesota. Filled with curiosities and old photos, the show offers a multidimensional tour across a storied landscape. But a sobering theme also laces through the stories, one that is present, not only along Highway 61, but across our state and our country: an enterprising white culture appropriating Native American mythology, art work, ideas and identity for the profit of the tourism business.

These are some of the stories behind the tales showcased in the documentary.

Highway 61

The highway was built on a well-worn trail used by the residents of the area. In Tales of the Road: Highway 61, Staci Drouillard recounts a family story of her great uncle who, when asked by authorities why he was walking down the middle of the highway stated: "My name is Charlie Drouillard and you built the road on my trail." This moment in the film underscores the fact that the construction of Highway 61, like that of so many highways in our state and across the country, destroyed communities in its path. For example, the roadway cut through the heart of what was once Chippewa City, home to 200-300 Ojibwe people.

Aztec Hotel

Like many entrepreneurs of the era, Rudy Illgen saw a need and filled it. As told in "Tales of the Road," Illgen was an early booster of North Shore tourism and decided to build a hotel to cater to the newly mobile tourists venturing north for scenic experiences. Instead of taking inspiration from the surrounding woods, the enormous lake or his own German heritage, Illgen chose instead to pattern his hotel after the "Aztec Indian temples [he] saw on trips to Mexico as a young man." Much like the still-standing Naniboujou Lodge in Grand Marais, the Aztec Hotel was decorated inside and out with patterns, colors and motifs that suited his idea of Native décor.

"To begin with, it was viewed as kind of this strange German [man] building this odd hotel and stuff," Illgen's son, Rudy, says in the show. "But then, as time went by, it became an interesting place for people to stop." Like much of the so-called “Native” diversions along the tourist road, the stereotype of Native culture – more than the real thing - appealed to tourists.

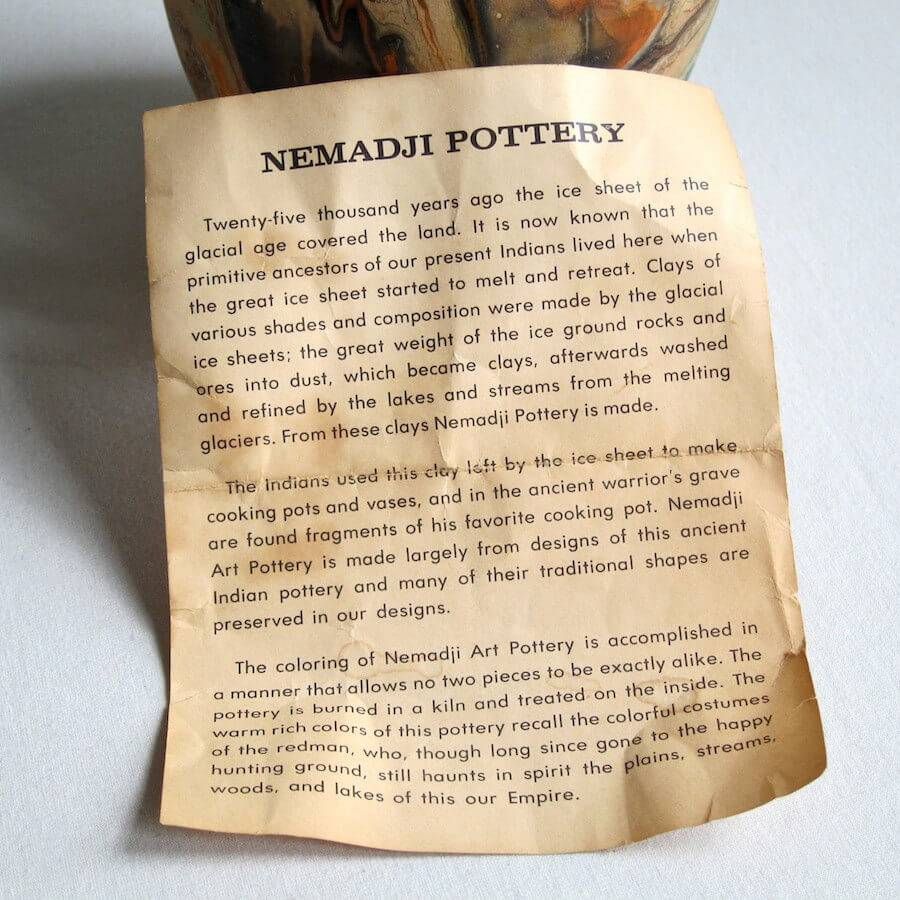

Nemadji Pottery

The Nemadji Tile & Pottery Company in Moose Lake started out innocently enough by creating decorative tiles from the local clay. But when the Depression hit, co-owner Clayton James Dodge saw the burgeoning tourism in the region as an opportunity to supplement funds lost to declining sales of building supplies. Once again, instead of relying on his own artistry or on drawing inspiration from the surrounding area to which these tourists flocked, Dodge created Nemadji "Indian" Pottery. In addition to the name, a fabricated history accompanied every single pot, one that suggested the items were made by Native Americans. Paired with an arrowhead stamp on the bottom, the pots sold extremely well – suggesting that tourists were drawn to an imposter’s rendition of Native culture and history.

Red Rock

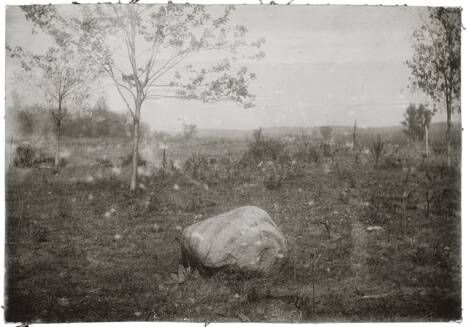

Hundreds of years ago near Newport, MN, the Dakota living there found a huge granite boulder on the riverbank amid the limestone and sandstone bluffs. State Archaeologist Scott Anfinson explains: "This was a granite rock and all of the river bluffs there are made out of limestone and sandstone. So how did this big boulder sitting on the riverbank get there? It doesn't make any sense. Water can't move it. It didn't come off the top of the cliff. So, basically a lot of the Dakota revered these things that were mysterious. They call it Wakan. … They would go there to pay their respects. This is where there's a lot of power. You don't want to offend it, so let's go and show that we respect the deity that resides in this rock or moved it there. It's all about paying respect."

Then in 1837, Methodist missionary Benjamin Kavanaugh founded a mission, intentionally locating it near Red Rock in an attempt to convert the Dakota who would come to pay their respects. While those conversion attempts were unsuccessful, the church drew people from far and wide to revivals or "Camp Meetings." Starting in the 1930s, the church moved several times, taking the rock along on each move. Despite its sacred symbolism to the Dakota people, the monument resides today with the Newport United Methodist Church.

But along with time comes a sharpened perspective. The Minnesota Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church "is in the early stages of making plans to return a granite boulder located on the grounds of Newport United Methodist Church to the Dakota, who consider the ‘Red Rock’ to be a sacred object."

“What I hope we can convey in returning the Red Rock," says Newport UMC's Rev. Linda Gesling, "is that we, as the white people majority culture, have benefited in many ways from so much that was taken from the Native people who lived here before us. Returning the Red Rock is a symbol of our acknowledgement of that.”

A Lack of a “Distinctive Regional Culture”

In Tales of the Road: Highway 61, host Cathy Wurzer taps into a WPA Minnesota guide that was once used as the pathfinder for the trip. The Federal Writers' Project (the part of the WPA that hired unemployed writers) elected Mabel Ulrich to head the creation of the Minnesota guidebook. According to Mnopedia, "Ulrich oversaw the Minnesota guidebook, but she often fought with the federal editors. They wanted a guide with a more romantic focus on Minnesota folk culture. Ulrich resisted their direction, because she did not believe Minnesota had a distinctive regional culture."

Woven into that notion of a “romantic folk culture,” is a certain fascination with Native America as a powerful lure that hooks tourists motoring along the eastern edge of the state. Altogether, infrastructure planners, hoteliers, potters and missionaries claimed the right to translate Native American culture into something that could be packaged and sold to American tourists hungry for the “exotic.” And into the vacuum of missing regional culture, they poured the ugly elixir of appropriation.

While it’s easy to catalog these details and shake our heads, it’s important to remember that Highway 61 has snaked through the Minnesota landscape for less than 100 years. This is not ancient history. While a trip along the route offers an unparalleled opportunity to enjoy the splendor of the state that is Minnesota, it also triggers an occasion for reflection on a sometimes difficult history and the ripple effects it has today.