Step into the 'Hall of Reflections' That Was Skid Row, Circa the Late 1950s

An excerpt from "The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis" by James Eli Shiffer.

Back in the winter of 2009, I embarked on one of the many strange quests that I have devised to make my life more interesting. I began searching for a collection of snapshots taken in the late 1950s of men whose names I didn't know, whose deeds never amounted to much and who died, as they lived, in obscurity. The pictures weren't particularly artful. Nor was the photographer, John A. Bacich, known for his technique. Johnny's images were a family album of people who had no families, men who had exiled themselves from what most people of the 1950s thought of as normal existence and found refuge in the alleys and cage hotels of Skid Row in the old river city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. I figured I had lost any chance of asking for help from Bacich himself, given how old he'd have to be by the time I learned of his existence, so I resolved to locate the missing photographs. I wasn't sure that the photos still existed, or what I would do if I managed to find them.

A year or so after I moved to Minnesota to work at the local newspaper, the Star Tribune, a friend had lent me a grainy video cassette of a 30-minute film titled "Skidrow." It was assembled from home movies shot by Bacich more than 50 years ago, in color, but, curiously, with no sound other than the narration by a rough-hewn voiceover that seemed lifted from film noir. From the first moment I watched it, Johnny's movie carried me into a lost world that to this day I haven't quite been able to leave.

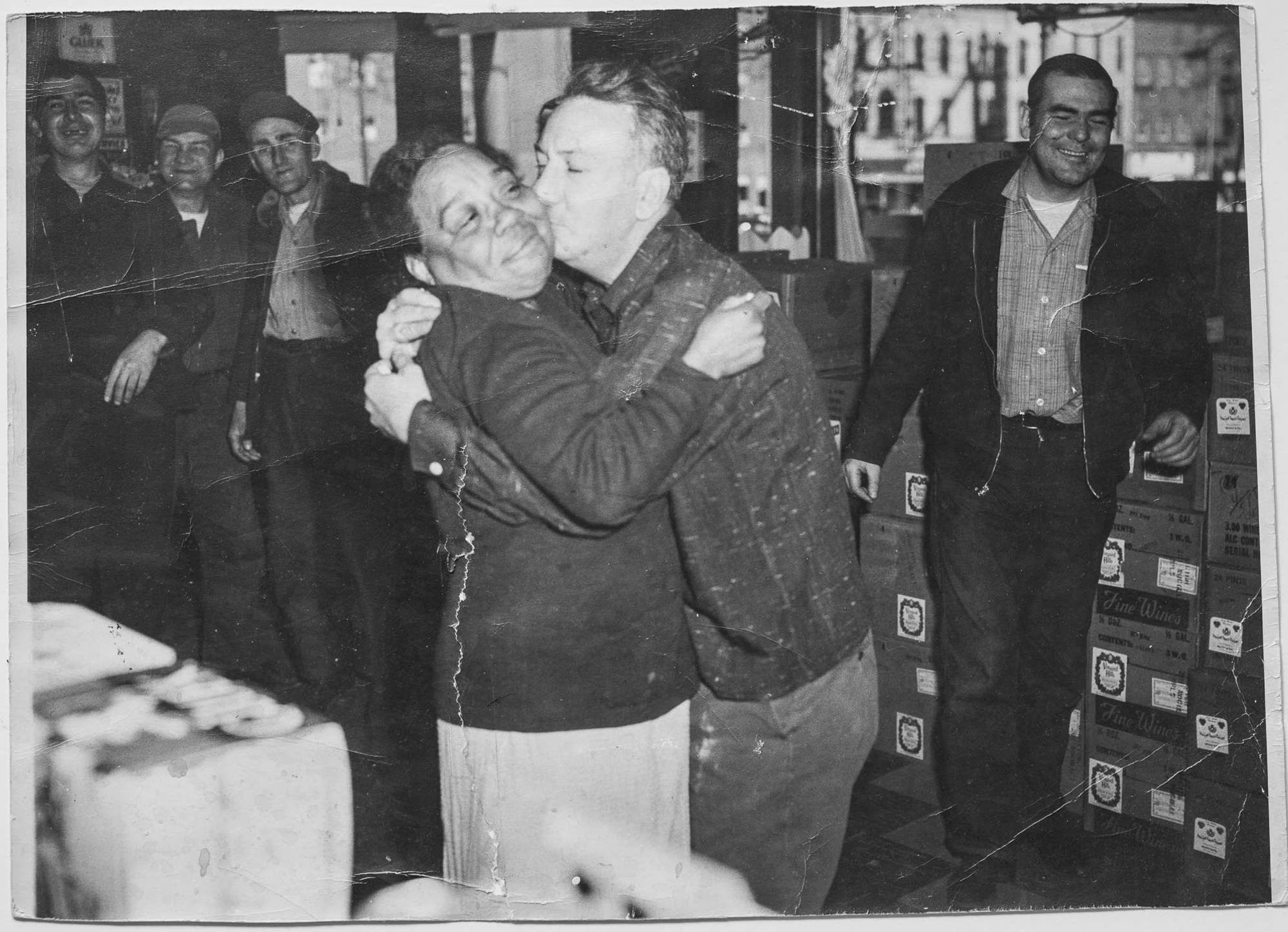

For a brief time in post-war America, when people were fleeing cities down brand-new highways to brand-new suburbs, Johnny moved in the opposite direction and opened a liquor store, a bar and a flophouse in the grittiest quarter of Minneapolis. The place changed him, like it did everyone who lived or worked there, but in his case, he ascended to a position of his own creation. John Bacich became Johnny Rex, the King of Skid Row. For some reason that I still don't quite understand, Johnny felt the need to document his subjects. Whenever something was going on, which was almost always on Washington Avenue, Johnny grabbed his Bell & Howell movie camera and ran outside to roll film. The men of Skid Row jostled and guzzled, wrestled and hugged, lived and died in front of Johnny's movie camera. Inside his establishments, he made still portraits of each of his men, usually when they were seated in front of a row of liquor bottles in the back room. Then he got the film developed into 3x5 snapshots with white borders. He pinned them in a neat line on the wall of his establishments, creating a frieze of weathered faces. When his businesses were evicted in the name of progress, Johnny unpinned those pictures and took them with him. It was those images that I was after.

That winter, I found a number for his wife in Florida and dialed. A telephone rang in a house on a Gulf Coast island. Then it stopped, and a recorded voice came on the line: "Hello, this is Barbara, please leave a message and I'll call you back." I felt a little let down. Part of me wanted to believe that Johnny Rex was still around, since all my Google searches hadn't produced an obituary for him, and I was sure that his passing would have warranted a mention, somewhere. But I also knew that his relationship with his hometown newspaper might have been fractious enough that he would have boycotted us, even in death. I left a message, explaining my interest in the photos and my hope that Barbara knew where they might be, if they hadn't been thrown away.

She called back the next day. I introduced myself and inquired about whether she knew what happened to the photos after her husband's...

"Well, why don't you ask him?" she said. Then she moved the receiver away from her head. I could hear her speaking to someone else in the room. "John, there's someone here from the Star Tribune who wants to know about your photos."

A month or so later, a fat envelope with a California postmark arrived at my bungalow in Minneapolis. A documentary filmmaker had been holding onto the photos for an art project that never materialized, and Johnny made a call to San Francisco and told him to send the photos to Minnesota. After some negotiation, the filmmaker probably realized it was one of those things he would never get to, so he sent them back to their city of origin. I ripped open the padded envelope and pulled out a black box, about the size of a thick paperback book, made of acid-free archival cardboard. I opened the box. Inside, curled against each other like old tarnished spoons in a drawer, were the brown studies of men, frozen in the 1950s. Their faces showed the wear of years of hard living. I saw gap-toothed smiles, deep lines, sunken cheekbones, inflamed noses, sometimes black eyes and fresh lacerations. They wore suspenders and plaid shirts, dungarees, occasionally a blazer, a collared shirt, even a tie. Most of these guys are clearly indulging the photographer, perhaps with the fear that if they didn't, that offer of a flophouse cubicle or fifth of muscatel wine would be rescinded. Some lean back on a worn-out looking couch. Others sit in an office chair, with a backdrop of shelves crowded with bottled liquor and wine. On the backs of the photos, sometimes Johnny had written a line or two in a neat script:

"A hard worker! Married an Indian. From the South."

"Wm. M. Johnston"

"Skeeter the Clown, tried to kill Johnson"

"Durrant! The tinsmith I taught a lesson to. He was artistically very talented"

"Headley the survivor! Both others were killed in car crash. Had an animal circus in Birmingham, Ala."

"Very sharp. Died on operating table. A nice guy, Schneider"

"He lived in South Mpls and never returned tho only a few miles from his wife and home"

"Ted Evenson, A carpenter and a good one when sober!"

"A nice quiet sort of man."

Others have nothing written on the back. Were they so well known that Johnny didn't need to write anything to remember them? Or had he already forgotten their names? Many of the snapshots were taken in an office that had a plywood wall in which a rectangular section, maybe 18 inches square, has been cut out. It's the kind of arrangement you find in certain diners, like the convenient slot through which the cook toiling in the back shoves the plates of greasy hash. In this case, Johnny had his men stick their heads through the hole to take their pictures. What you notice, if you look at them long enough, are what's pinned to the plywood above their heads. It's the snapshots, all the photos Johnny took before that one. You're looking at a photo of the photos, like a hall of mirrors in which the reflections recede, smaller and smaller, but infinitely, into the distance. Then you notice that the photos in your hand are perforated at the corner by pinholes, or they have been pinned and unpinned so many times the corners have fallen away.

You realize that this hall of reflections takes you 50 years into the past, back to a time when the largest city in Minnesota was home to the most notorious Skid Row in the upper Midwest, the biggest main stem from Chicago clear to Spokane, and its king was a short fiery guy named Johnny Rex.

After our first phone call that winter day, I spent the next three years talking to this man, on the phone and face-to-face, recording our interviews, doing whatever I could to jog his recollection about a place that he had done so much to document but had not existed for 50 years. He had reached that age when men do not feel self-conscious about pushing the buttons on their mental jukebox and replaying one greatest memory after another, as long as someone is sitting there to listen. I would never say that I knew him well. Nor did I want to probe too deeply into the many sore points of his life. His combat experience in World War II was completely off-limits, his first marriage was clearly troubled, and he didn't want to talk about his children, either. Skid Row, on the other hand, had given him something like fame. Not at the time, but later, long after the Victor Hotel and Rex Liquors and the Sourdough Bar were closed and obliterated forever from the city's landscape, and Skid Row, also known as the Gateway District, or the Lower Loop, was preserved only in memories. Somehow Johnny knew that people would want to know about this place, and that instinct would ultimately change the city's opinion of him.

Getting possession of Johnny's snapshots had a peculiar effect on me. I wanted to know everything I could about this place, and that meant seeing just about every picture ever taken of it. I learned that Johnny wasn't the only person who photographed the final days of Skid Row. Actually, the closer the end came, the more photographers swarmed into this doomed place, although for different reasons. In its decade-long crusade for the demolition of the Gateway, the newspapers went to extraordinary lengths to display its degradation. One photographer outfitted an alcoholic with a flashlight in his pocket and probably gave him some money to go get hammered. The resulting image showed the light trail of a drunk staggering down the sidewalk. Journalists became somewhat more professional as the end approached in the late 1950s, and the Minneapolis Tribune even commissioned a street-by-street architectural survey of what would soon be lost to the nation's first downtown urban renewal project.

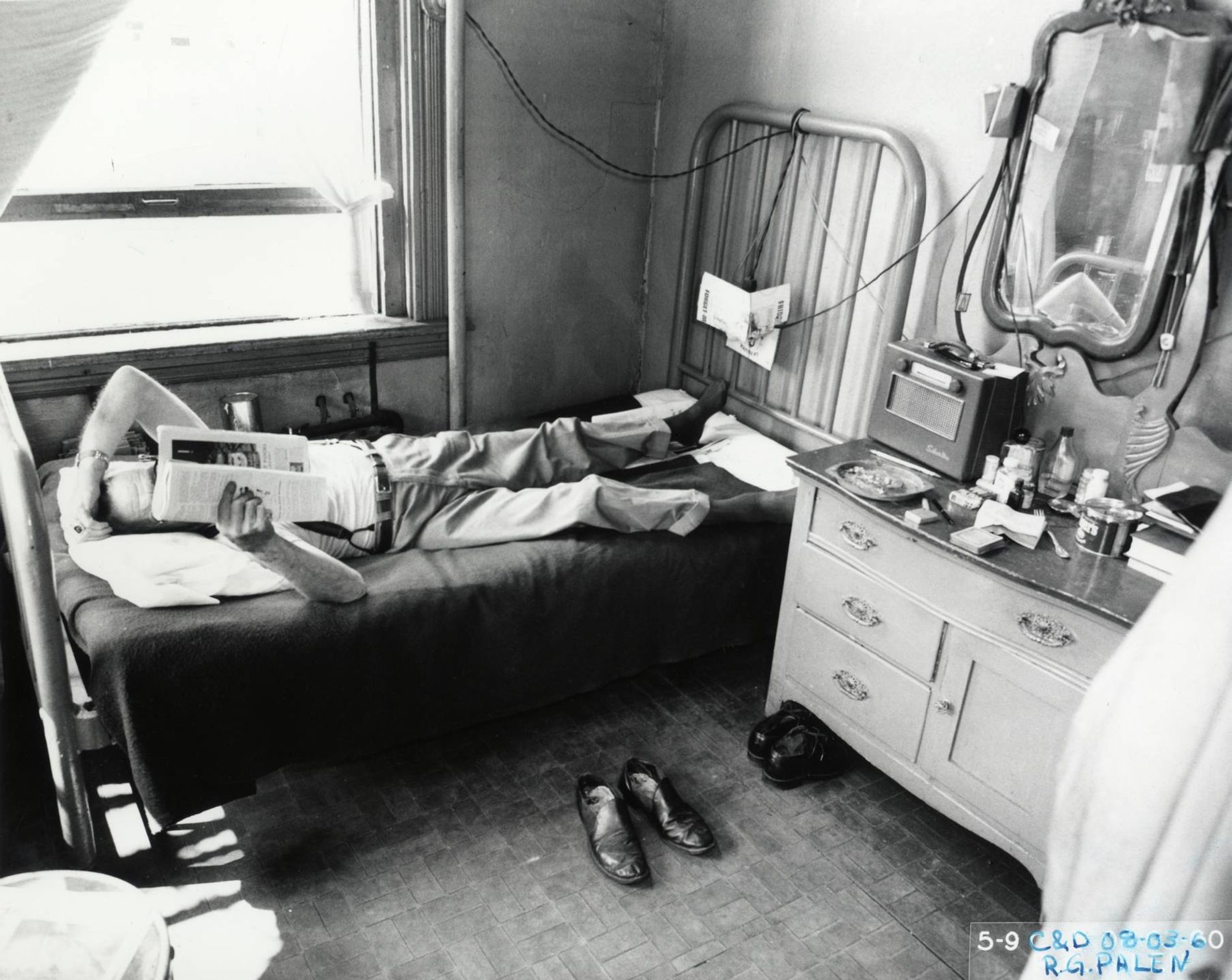

In some forgotten boxes in the city archives, I found file folders full of black-and-white prints taken by Minneapolis Housing and Redevelopment Authority contract photographers. They had gone into every building in the neighborhood to document the decrepit conditions, and their cameras found every loathsome toilet, miserable hovel, ancient octopus-like boiler, rusty slop sink, attic splattered with pigeon excrement and basement bottle dump. Many of the old storefronts and hotels were abandoned by this point, and for those that weren't, any workers or tenants who happened to be in the pictures were entirely accidental subjects. It's as if the bartenders and seamstresses and potbellied pensioners were the last members of a tribe looking on helplessly as a colonizing empire flattens their forest. Even more photos are preserved in the pages of a dissertation from a University of Minnesota sociology student, Keith Lovald, who was deeply involved in a research project that aimed to understand why men lived in Skid Row. Lovald rented a room above a Gateway bar and used a telephoto lens to spy on the sidewalk. He caught a panhandler in the act. He witnessed a "bottle gang" in their alleyway ritual and captured the moment when a landscaper drove up and hired a laborer off the street. Other University photographers traveled to Skid Row as well, but they wanted to create art, not scholarship. Jerome Liebling arrived at the U from New York, where he had been schooled in the Photo League's socially conscious philosophy of photography. Liebling was well on his way to becoming a giant of 20th Century photography and documentary filmmaking when he taught a class that encouraged his students and colleagues to shoot pictures in the Gateway, "a rough, densely-packed, provocative arena, completely different from the established middle-class neighborhoods or the evolving suburban landscape of the Twin Cities," an art historian would later write. Their photos captured men in line at soup kitchens, dozing in mission dormitories, posing in doorways that would soon disappear. They stare at the photographer, or they look away, as their neighborhood falls to pieces.

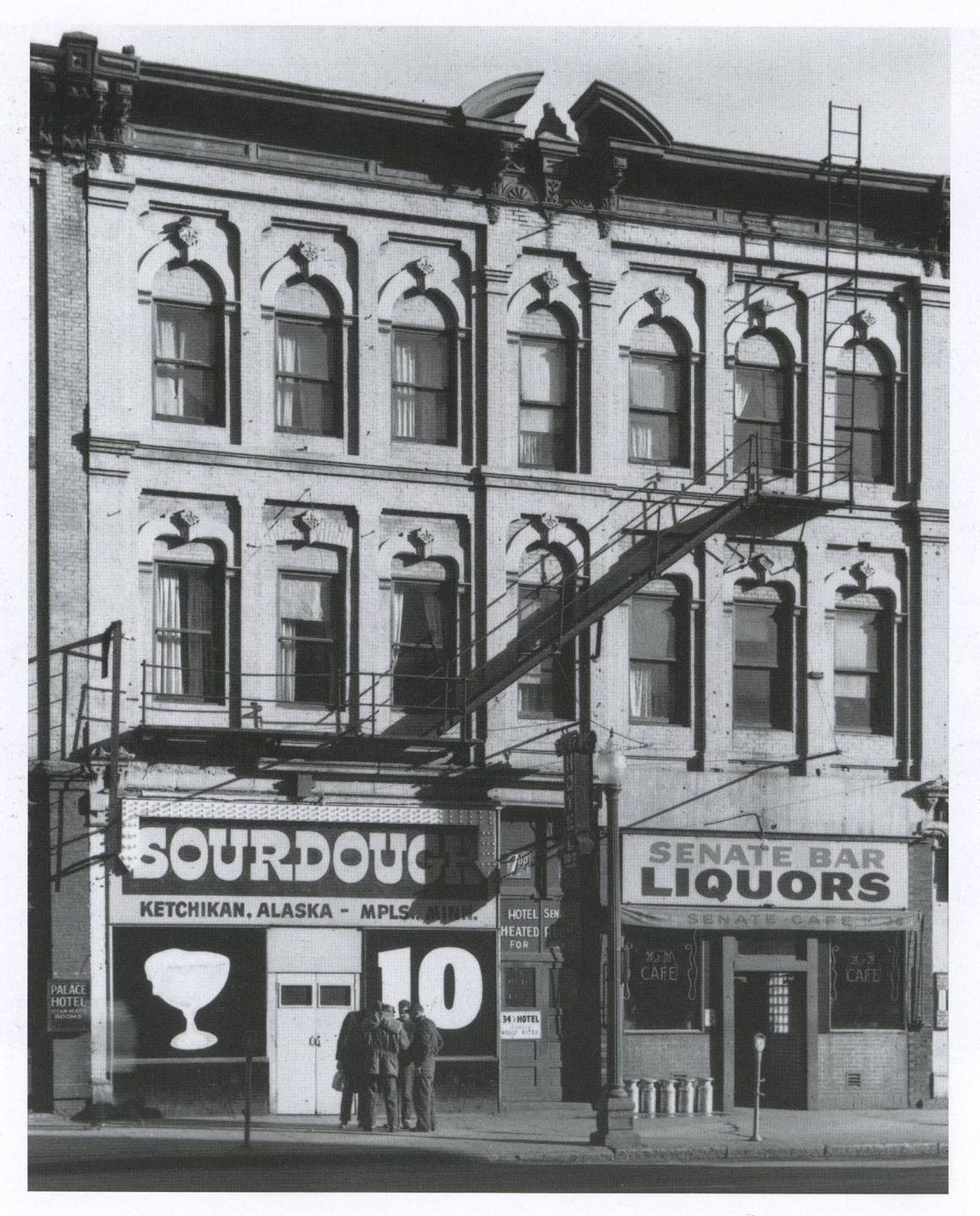

One morning, maybe in 1960, one of Liebling's proteges, Robert Wilcox, stood across Washington Avenue and aimed his camera at a once elegant three-story commercial building. The shadows cast by the rising sun set 14 windows deep in shadow, like eyes sunk in their sockets. A broken pediment provides an architectural flourish atop the cornice. Yet the building is sullied by a fire escape, artlessly bolted to the facade. It drops diagonally across the front of the building and ends at a platform above the first floor. Then you see the two garish storefronts - Senate Bar Liquors on the right, then on the left:

"Sourdough

Ketchikan, Alaska Mpls, Minn"

A goblet overflowing with a great head of foam is painted on one side of the storefront. On the other side, an immense "10," the bargain price of that colossal beer. In front of the Sourdough are four men, standing in a tight circle as they wait for Johnny to open his bar, paying no attention to the photographer across the street.

Johnny Rex likely would have never known that his bar was photographed, if not for an art exhibit of Wilcox and Liebling's photos, titled "Faces and Facades," at the University in the early fall of 1961. A young woman working her way as a waitress through law school happened to go, and saw the picture. Then she went and told Johnny, a guy that she had met carrying cocktails to customers of the Carousel Bar on Hennepin Avenue. Her name was Barbara Madsen, and she had fallen in love with this character, and before long, Johnny and Barbara would be married. For now, she wanted him to meet the art photographers at the U and tell them about all the home movies he had made of the men he called "gandy-dancers" and the crazy things they did every day on the Avenue.

It had been a rough year for Johnny Rex, full of turmoil, personal loss and trouble with the city. But if someone at the U was interested in his pictures, then he would oblige them. He met with Liebling. The photographer was so excited about Johnny's films that he involved his students and sent them to shoot additional footage, stitching the whole thing together into a coherent half-hour silent reel. The wrecking ball was already in full swing by this point, and within two years the buildings that made up 40% of downtown Minneapolis would disappear. The already rich photographic record of an American Skid Row would be crowned by this remarkable movie, although it would take a good 30 years before anyone else realized it.

The movie features several episodes of two men, Emil Teske and Nick Fiestal, both old railroad workers from Indiana. They are engaged in a peculiar kind of sidewalk wrestling that involves each one maintaining with a tight grip on the other's nose. They do it in rain, snow and shine, and sometimes tumble onto the pavement in their bizarre nose-pulling combat. They always come up smiling, though. This film is no syrupy view of the past. Violence and degradation were present every day on Skid Row, and Johnny Rex felt compelled to film that as well, in blood-red Technicolor. Some parts of "Skidrow" are truly hard to watch. People who had hit bottom, then broke through and plummeted into the proverbial basement. There's a dapper fellow in a cream colored jacket and white fedora with a black band. John tells us the guy used to play piano with the Lawrence Welk orchestra, whose show started with the rising bubbles and was beamed into TV sets every Sunday night across America. The musician shows off for Johnny's movie camera, flexing his fingers as if he's going up and down the keyboard in the air. He looks good now, John says, but he doesn't look like that after he's been drinking. Then he proves it, later in the movie, when the piano player has a week's beard on him, his jacket is gone, and now he's paying no attention to the camera. He's in a circle of men who are crowded into a dimly lit room. They're passing a jug around and everybody takes a deep swig. The piano man has a cigarette in his hand and an intense focus on the task at hand, and you can't help feeling that he's thrown away something valuable in this dark den of drunks.

Some people would have been scarred by these experiences. Joseph Mitchell writes about a habitue of Old McSorley's Ale House, one of New York's most famous bars. The man used to run a chain of Bowery flophouses, and he vowed on the day of his retirement to get drunk and stay drunk. "He says he drinks in order to forget the misery he saw in his flophouses; he undoubtedly saw a lot of it, because he often drinks 25 mugs a day, and McSorley's ale is by no means weak." Johnny more closely resembled another New York character from the same era, a saloonkeeper named Sammy, "mayor" of the Bowery and a friend to Weegee, the photographer behind the "Naked City." Sammy personally tossed troublesome drunks from his bar, but also was "a friend and ready to lend a helping hand… lending money so a man can get cleaned up, food and a room while he is getting over a hangover."

Johnny never succumbed to the bottle, or nostalgia, for the matter. Yet he felt keenly that the city's forced removal of 3,000 men broke up a real community, and that someday people would want to see what it was like.

I was one of those people. I looked at all of these pictures, and tried to reconstruct Skid Row in my mind, every bar, every pawnshop, lunch counter, barber college, job broker, second-hand store, storefront mission, and then searched my city for some vestige of it. All I could find were the same blank concrete walls and asphalt parking stalls that Minneapolis felt were such an improvement over its historic streetscape. "Not a trace of it now," Johnny told me, in his movie, and he was right, but I kept looking, and keep looking.

This book is my attempt to rebuild that place, and understand what happened there in its final days, with what I've learned from two dozen conversations with Johnny in the twilight of his life, and old newspaper clippings, academic studies, city reports, other history books, and hundreds and hundreds of photographs. Skid Row was defined by its institutions, all of which Johnny Rex touched in some way. It offered the men an escape to a warm sea of booze that would also drown them. It gave them a cheap place to sleep, provided they didn't mind chicken wire for a roof and the smell of men packed tight. It offered to save their souls and understand their psychology and cure their bad habits, or just give them as much alcohol as they could handle and then some. It was the arena for the worst and best instincts of human nature.

I probably will never resolve the mystery of why Johnny photographed the men he called his gandies, but I know that this act goes to the heart of why he came to Skid Row and how he outlived that place, the men who lived in it and his city's antipathy toward him and his kind. I am grateful that Johnny Rex was willing to take me there, for one last trip into the end of an American Skid Row, and what follows is the story of that journey.

Excerpted from The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis by James Eli Shiffer. Published by the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2016 by James Eli Shiffer. Used by permission.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

In the years between the world wars, Minneapolis residents gathered in the city's parks on balmy summer nights to raise their voices in song. Those "community sings" events eventually took on a competitive note as each community tried to out-sing those within a stone's throw. Discover how "participatory, public entertainment clearly held enough power and potency to draw thousands of people from their homes with the singular motivation of singing in unison."

Just as the community sings events were unfolding in Minneapolis parks, notorious gangsters flocked to the "saintly city" on the other side of the river. Explore this slice of local history in which the criminal underworld hobnobbed with high society.

The iconic club known as First Avenue has long been a sort of ground zero for musical lovers of different stripes to gather. Take a trip in a time machine to visit the early days of the venue – first, when it was known as The Depot and later as Uncle Sam's.