Songs of Home: 'Open Letter (to a Landlord)' by Living Colour

A song that carried the weight of housing injustice resonates just as much now as it did when it was written in the '80s.

As a result of making the film Sold Out: Affordable Housing at Risk, I’ve become keenly aware of the issues of housing in Minnesota. I’ve often admitted that the process of making that documentary illuminated housing insecurity for me in ways that have changed me forever. But my personal journey into understanding housing issues isn’t over yet. Nor did it begin with Sold Out. It began with a rock band in 1988.

Time to hit "Rewind" on the boombox tape deck and put on some acid-washed jeans.

I’m a proud Minnesota GenXer. Our angry little cohort is sandwiched between the massive army of Baby Boomers and their equally sprawling Millennial offspring. Just us against the world: bitter, disillusioned, finding consolation in art and music. I grew up on folk music and late '60s rock, two divergent genres that both, in their own ways, championed social change. With Pete Seeger in one ear and Neil Young in the other, I was ready for a new message.

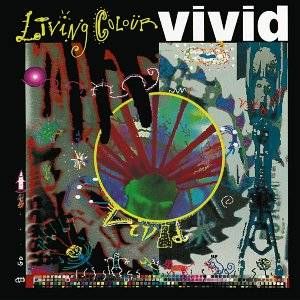

So it was at a very formative time in my youth that a band like none I’d ever seen released their first album. Living Colour’s 1988 Vivid album blew my mind: hard-rocking jams with a socially conscious voice from a highly virtuosic, all-Black band. Living Colour shook up my world like a grenade into the highly flammable fog of awful hair bands, cheesy power ballads and pop darlings. There was an explosion, at least in me - and it felt good.

Their massive hit, "Cult of Personality," is track number-one on that album. Suddenly, everybody knew Living Colour, and hopefully knew that they had a social message. But my hunger for Living Colour was deeper than one hit, and I consumed that album over and over and over, front to back, back to front.

For decades, Twin Cities PBS has covered stories about homelessness and affordable housing. Check out our collection “Under One Roof: Stories of Minnesota’s Housing Crisis.”

Slowly, one track in particular began to stand out. It lacks the aggressive, playful, funky humor that permeates every other track. Instead, it starts out with a slow, poignant guitar arpeggio and lush, stacked harmonies, followed by a haunting chorus which frames the entire song:

Now you can tear a building down

But you can't erase a memory

These houses may look all run down

But they have a value you can't see...

"Open Letter (to a Landlord)" is a raw, brutal, mournful response to a broken and unjust housing system, a system I hardly knew existed. It was an awakening.

As a white kid growing up in a nice Saint Paul neighborhood in a house that my family owned, I had little exposure to any of the challenging edges of housing. I do have memories from grade school of visiting some immigrant friends at their apartments. I didn’t recognize the neighborhood, the street names, the strange smells in their kitchens, the discount food brands in their pantries. Only when I got older did I realize they lived in “the projects."

This is my neighborhood

This is where I come from

I call this place my home

You call this place a slum

By the time Vivid was released, I was starting my high-school career at St. Paul Central, a school known for its culturally diverse environment. I suddenly had friends of every color, culture, clique and clan. I could visit them and see how different their experiences were from mine. The coincidence of that album’s release and my exposure to different people’s life experiences gave me a new window into race, poverty and inequity in America, in Minnesota, in Saint Paul. And this song - this angry, sobbing, seething, weeping, empowering song - suddenly made some sense.

Okay, now hit "Fast-Forward" on that boombox and put those jeans back in the attic.

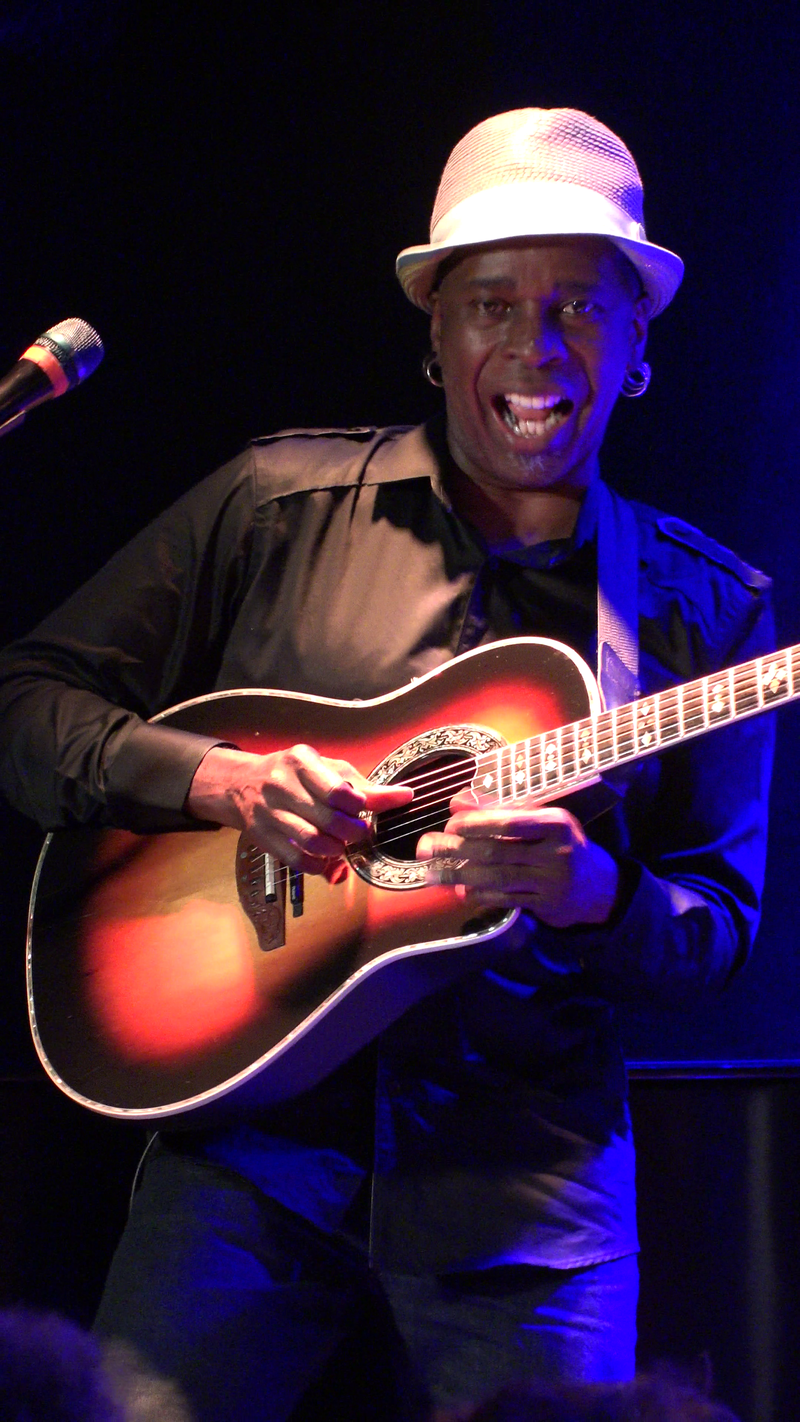

In an effort to understand the origins of the song’s lyrics for this article, I contacted one of the songwriters, Tracie Morris. She is a poet, experimental performance artist, writer, professor, actor and a hundred other forces-to-be-reckoned-with.

Morris was coming of age in New York City at the same time as the members of Living Colour, and their worlds collided around 1986 when she called the number on a flyer for the Black Rock Coalition to get directions to a BRC party. Living Colour guitarist and founder Vernon Reid answered. The rest is history, and they remained friends and collaborators for many years. Morris credits the BRC and its ecosystem of black artists for giving her the push to move from a planned career in law into creative writing and art.

“In the '80s, music was really segregated,” Morris notes. “No matter what kind of music you were making, if you were a Black artist, you were in the R&B section. Even Prince, a pretty well-established rock guitarist there [in Minnesota]. And people were like, ‘Why is Prince in the R&B section?’”

Reflecting on the origins of the song in question, Morris remembers, “The song came about because Vernon called me. I was a writer; I was also a political speech writer for the [BRC]. He had written the lyrics to "Open Letter (to a Landlord)," but…he was stuck in one spot. He said, ‘I need some lines here, and I can’t think of any lines here.’ I think one of the reasons why he asked me - because I was not a songwriter at the time - was because I had written a lot about political issues. I was an activist person.”

“The band did address political issues,” Morris emphasizes. “It’s not like they weren’t being political until that point. They were all struggling artists and trying not to get evicted and all of that stuff, as well as the issues that people saw in their communities. Especially downtown artists… Especially the Lower East Side and Soho, where many of our meetings took place and basically where we hung out. It was personal, it certainly affected our friends. We didn’t realize we were part of some larger trend that was happening in real estate, which is ‘Look where the artists go… [let the artists] raise the cool factor and then evict the artists.’ We just thought people were getting evicted because prices were going up. But it wasn’t just that. We were the people they were tracking to figure out where to evict people, where they were going to gentrify.”

You want to run all the people out

This what you're all about

Treat poor people just like trash

Turn around and make big cash

Morris continues, “The song is focusing on the people who are losing homes, and not the people who are moving in. 'Open Letter (to a Landlord)’s' refrain is, ‘You can tear a building down but you can’t erase a memory.’ So it’s about the loss of place. It’s not about the transplantation of someone else. If it’s a tenement or an industrial loft space, then they would tear that down to build high-rises and fancy condos. So it wasn’t just about displacing, it was also about erasing a particular place. I don’t think we could have imagined at that time how big the forces were around us, and what it means to displace people. Because…that song, they’re singing about and playing about regular people. Where will the regular people go after you’ve displaced them?”

We lived here for so many years

Now this house is full of fear

For a profit you will take control

Where will all the older people go?

And then the conversation takes a startling turn:

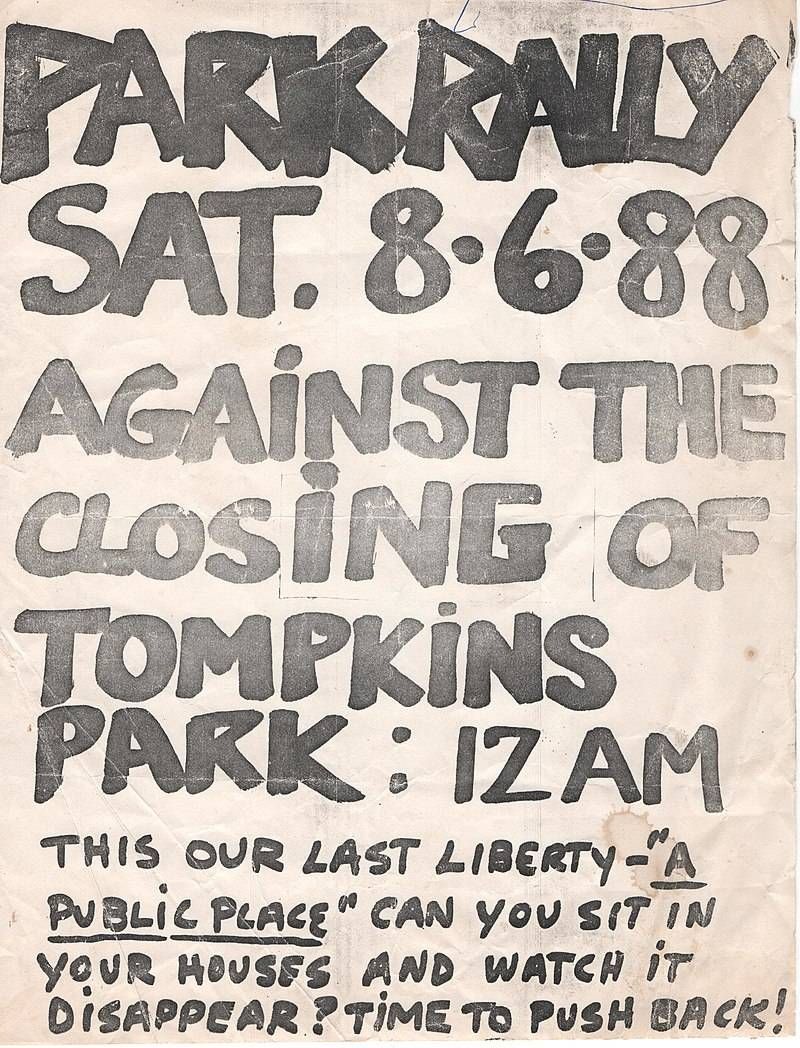

“Of course this was a huge deal on the Lower East Side because of the so-called riots - but they were riots against people - in Tompkins Square Park.”

While the song was written and recorded before this event - not quite three months after the album’s release - violence erupted in an encampment of homeless and displaced people, homeless youth, and others living in and around New York’s Tompkins Square Park, long a symbol of progressive union activity and solidarity movements. Over the course of several days, protesters and others clashed with police in a series of rallies and riots. By all accounts, there was bad behavior on both sides, culminating in a two-day clash in early August 1988 in which police brutally assaulted protesters, resulting in 100 police brutality charges. However you see it, this was an ugly chapter in New York City’s housing history, a chapter of which I was unaware until Morris mentioned it in our conversation.

You've got to fight

You've got a right

To fight for your neighborhood!

You've got to fight

You've got a right

To fight for your neighbor!

And then as the song ends on that empowering line, with the guitar’s feedback wailing in the background, the haunting sound of an NYC elevated train clatters by. It’s heartbreaking and beautiful.

The origins of the song are not a Minnesota story. But my awakening through that song - to the harsh realities of being Black in America, poor in Minnesota, housing-insecure in Saint Paul, and to finding your creative voice to address injustice - that’s part of my story.

This story is part of the collection, Under One Roof: Stories on Minnesota's Housing Crisis, which is funded by a grant from the Pohlad Family Foundation.

More than 10,000 Minnesotans are homeless, a number that is a record-high for the state and a 10-percent increase since 2015 - but the problem doesn't just persist in the Twin Cities. One Greater Minnesota reporter Kaomi Goetz explored how homelessness is also impacting rural communities across the state.

“Get a job!” “Go to a shelter!” So many misconceptions swirl around the issue of homelessness in Minnesota, many of them driven by persistent stereotypes. Explore five of the most prevalent – and false – notions about what it means to be homeless in our state.

Tenants and landlords, alike, have specific rights, a topic we explore in this series of multilingual videos in English, Hmong, Karen, Somali and Spanish.