'Slavery by Another Name' Reissued: The Historical Truth of Neo-Slavery Beyond Juneteenth

Juneteenth commemorates when enslaved African Americans in Texas learned of their freedom through the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War, or the "slave holders rebellion," as many referred to it at the time.

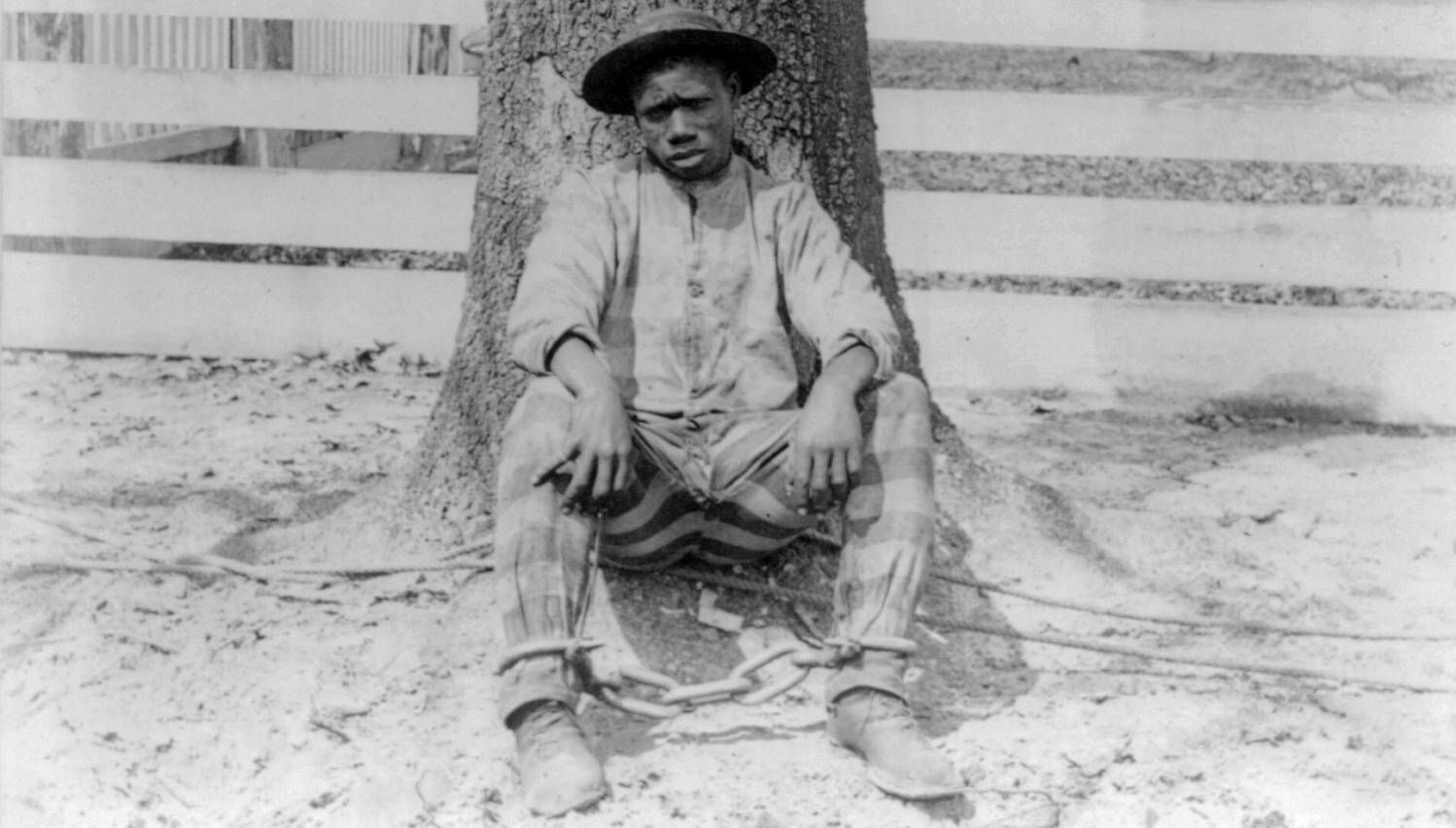

But in the decades following Reconstruction, the historical truth is that peonage, debt slavery, share cropping and other forms of neo-slavery would mean that labor-inducing bondage continued in many parts of the South up to World War II. So, in a very real and lived way, American slavery ended in 1945, not in 1865.

This grim reality was brought to fuller focus in Douglas A. Blackmon's Pulitzer Prize winning book Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II.

PBS is reissuing the film adaption of Blackmon's work, which he co-executive produced with Twin Cities PBS. In the nearly 10 years since it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, the film continues to live on in classrooms and in community, engaging people in conversation and influencing visual art, dance, music, scholarship, classroom instruction, new documentaries, podcasts, feature films and journalism.

I worked on the film and asked Blackmon to reflect via email on the connections between past and contemporary horrors like the murder of George Floyd.

The book's popularity and impact connected you to descendants of neo-slavers, as well as to descendants of the Black people they enslaved. Meeting them through the film project, I was struck by the resilience of the African-American descendants and the courage of the white descendants in confronting their family's history. How are these families doing years later?

Douglas A. Blackmon: I still hear from many of the descendants still grappling with the history they discovered through the book and film. For most, I think it continues to help people feel they understand the truth of their origins — and the country's — in a helpful way. At the same time, there are also still some descendants of people that did terrible things who continue to show frustration and denial that this history is being discussed. That just proves how necessary it remains.

WATCH: Slavery By Another Name author and co-executive producer Douglas A. Blackmon discusses his own journey to writing the book and interviews descendants of some of the historical figures he features.

You were quick to take on the white supremacists in Charlottesville during their deadly gathering in 2017. For years, you've talked candidly about race and racism. Why is that important for a white male Southerner to speak up on these issues?

Blackmon: When I have tangled publicly with white supremacists, it's not really about trying to persuade them to think differently. They are mostly lost for good, already. What's much more important is just demonstrating that any of us can — and must — squarely contradict people spewing such terrible ideas. Partly that's to make clear that no one should be influenced by those voices, but also to show that discussions about hard things are not as difficult as a lot of people think they will be. My philosophy is: Jump in. The more we talk and the less we worry about it, the better everyone will be.

Today we're seeing a doubling down on Jim Crow-like voting laws and backlash to anti-racist education. How can narratives like yours work to combat these regressive efforts?

Blackmon: These new efforts to hide the realities of the legacies of slavery and American apartheid are terrible, of course. But they are also a kind of proof of the progress we're making toward a more equitable society. As a more and more diverse and honest America emerges, the people made uncomfortable by that are going to fight even harder at times to stop that progress or avoid honest dialogue. Hopefully, work like Slavery by Another Name — which is grounded in vast, verifiable, factual history — gives us all bulwarks that help us withstand the deceptions and delusions of people trying to take our country in the wrong direction.

This past year saw a heightened focus on policing and systemic racism. Slavery by Another Name points out connections between law enforcement, incarceration and these systems of neo-slavery. Can you offer some examples of how this worked?

Blackmon: What Slavery by Another Name shows more than anything else is we can never just assume that the incredible power of our justice system — and police in particular — will always automatically do what is just and reasonable. The truth is that most police and prosecutors and judges want to be fair and honest. But we still all must be vigilant in making sure those powers of government are not misused by those who are misguided, incompetent, out for themselves only, or explicitly racist.

When we were on location in rural Alabama, I encountered my first Confederate monument. You provided me some context and backstory of these markers, years before they were thrust into the foreground of American consciousness. Where are we now with how to deal with these monuments?

Blackmon: The Confederate monument debate has been incredibly positive and uplifting to me. We should all remember that, while what happened in Charlottesville and the other turmoil around monuments has sometimes been ugly, it has all been a reaction to — a backlash against — the tectonic change in Americans' understanding of what those statues really represent.

Twenty-five years ago, when I first started suggesting that the Confederate monuments were a serious problem, I could find almost no one else who thought they mattered at all. And the defenders of the statues — white supremacists and propagandists like the Sons of Confederate Veterans — made it clear that they were almost maniacally devoted to preserving those monuments by any means, including violence. But now, the overwhelming majority view is that those tributes to racism and treason don't belong in our public spaces anymore. That's incredible progress.

What other hidden histories warrant research and revealing?

Blackmon: We still have only barely begun to understand how deeply our current world was formed and shaped by white supremacy. There remains endless work to be done there. That is also the case with the history of what was done to the Native peoples of North America, the benefits accrued to others, and trying to untangle that legacy. There is always more.

What do you hope is the legacy of the film Slavery by Another Name?

Blackmon: An understanding that seeing the truth of the past — even when ugly — is the liberation of the future.

Watch Slavery by Another Name online at TPT.org, or check your local PBS station's schedule for broadcast dates and times.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by grants from the Otto Bremer Trust, HealthPartners and the Saint Paul & Minnesota Foundation.