Racism Is Killing Twice As Many Black Babies in Minnesota

Dayana Bella-Marie Campbell was loved on the night that she died.

It was an average day, and Dayana’s parents poured time into their first-born. Her mom, Stephanie Pollard, sat down to watch cartoons with her. A favorite was Princess and the Frog, a story about a Black woman struggling to be human again. Pollard bathed Dayana, washing her full head of hair, which had amazed doctors. And as the night ended, Pollard put Dayana in her father’s hands, kissed her and said, “I love you.” It was the last thing Pollard told her daughter. Pollard woke the next day to find that Dayana died in her sleep. She was three months old.

Doctors could not explain how Dayana died. They said she was healthy. One coroner said sudden infant death syndrome could be the cause. Whatever the reason, Pollard is now one of hundreds of Minnesotans whose child died before their first birthday. Many of them are Black.

African-American infants are dying at twice the rate of white infants, reflecting decades of health inequity that has been drawn by racial lines. The COVID-19 pandemic is bringing new challenges to the issue, and erasing that disparity means addressing systemic racism that has derailed the lives of countless families.

The morning that Pollard found Dayana, she begged God to take her instead. When that didn’t happen, Pollard changed. She cried for days. Holding children felt unbearable, and even news of missing children reminded her of Dayana.

The pain is still there, but Pollard has found comfort in other mothers who also lost their infant children. Although their children passed in different ways, they share a history of being discriminated against.

“We get looked at a lot differently than some moms that lost their child [in] different ways. Sometimes people just want to come and hear the story and see if you did anything to your child,” Pollard said. Her second daughter, Ivory Campbell, cooed as she spoke. “It’s a horrible bond to have… But losing your child, it does help you create a bond with other moms that have lost their child as well.”

In Minnesota, most of those moms are people of color.

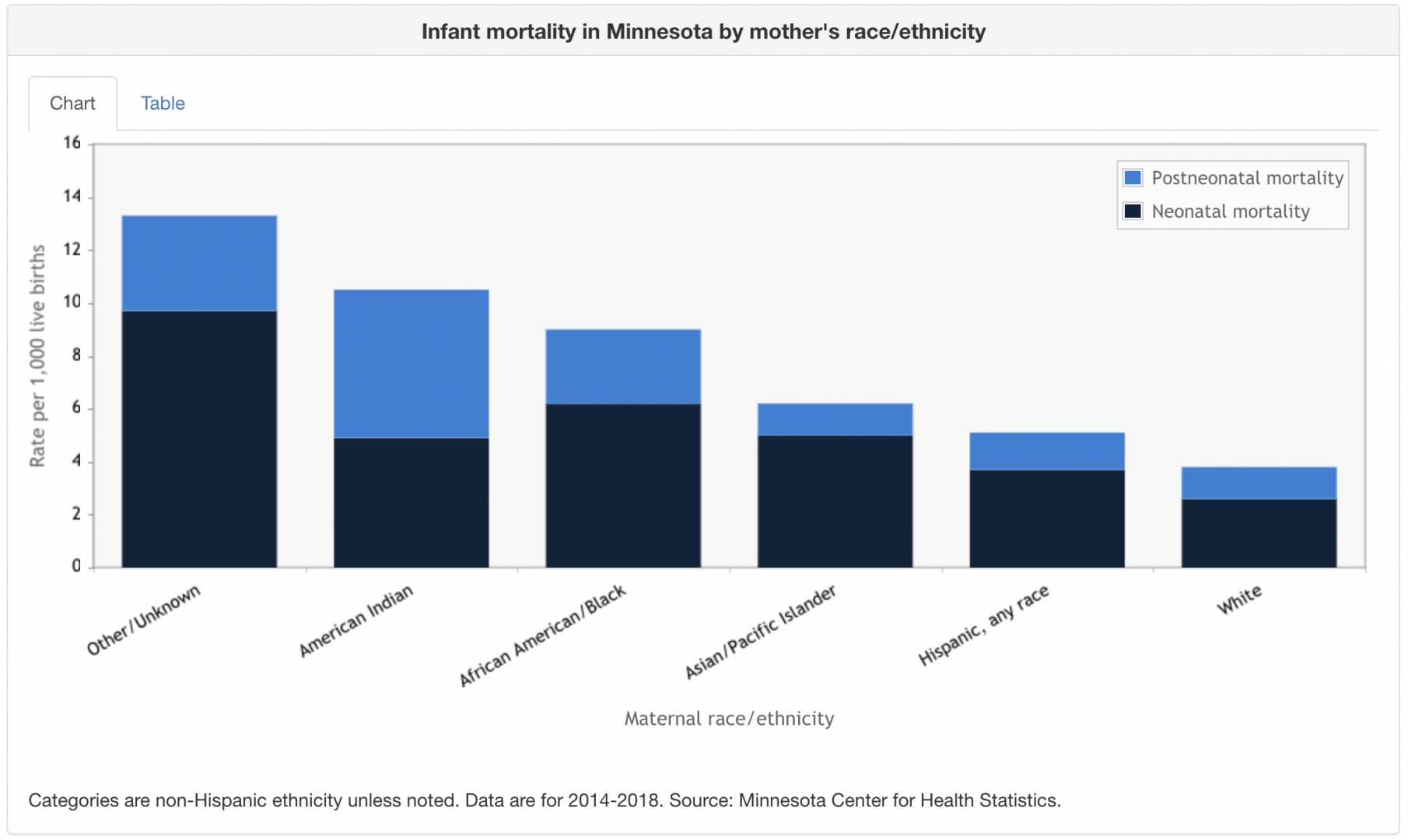

Data from the Minnesota Center for Health Statistics shows that infants of color are up to 2.6 times more likely to die than white infants. The highest rates are among Native American people, who make up just 1% of this state’s population.

With disparities in health care driving these unequal rates, many people have turned to doulas - professionals trained to support mothers before, during and after their pregnancy. Akhmiri Sekhr-Ra has been a doula here for decades and now works as a Chief Family Development Officer for the Cultural Wellness Center in Minneapolis. A lot has changed since Sekhr-Ra started practicing in the 80’s. But one thing remains the same: Few doulas are people of color.

“You’re more comfortable in your skin if somebody who looks like you is there. You don’t feel like you’re isolated and alone,” Sekhr-Ra said. “There needs to be more people who look like us in the field.”

Jennifer Almanza, a certified midwife and clinician at University of Minnesota Physicians, has found that racial consistency in health care can halve the chances of Black babies’ deaths. Yet 90% of midwives in the U.S. are white.

“The U.S. is the only developed country with a rising maternal mortality rate. We know that many of these deaths and injuries can be prevented,” Almanza said. “We will not bridge the gap in maternal outcomes until we are able to fully address racial disparities in health.”

COVID-19 has worsened those disparities. More people of color in Minnesota are filing for unemployment, going hungry, and contracting and dying from the disease. Fewer have been vaccinated or have health insurance to help them.

Worse yet, Sekhr-Ra said COVID guidelines are separating more mothers of color from doulas and support systems that are vital to their babies’ health. Closing the gap in infant deaths means addressing what causes these disparities. Some experts say that the root cause is racism.

Stephanie Pollard had heard horror stories of women dying or being misdiagnosed while pregnant, but she was not prepared to lose her daughter. Pollard journals to Dayana every day and says that her thoughts on the healthcare field have changed. She is more cautious now and feels that people should focus on the issue instead of sweeping it under the rug.

“Be more open-minded to treating African-American women and children a little bit better in the healthcare field and not just being like, ‘Since your family had cancer or diabetes, this is what’s most likely going to happen,’” said Pollard. “It doesn’t have to happen.”

Dr. Rachel Hardeman might agree. Hardeman studies reproductive health equity at the University of Minnesota and said that gaps in infant death rates persist, even when you account for healthcare access and risks such as smoking.

“At the crux of why we’re seeing these racial disparities, these racial inequities in infant mortality, is structural inequity and structural racism,” Hardeman said. “It’s not a coincidence that the two populations that have been historically oppressed, historically marginalized throughout our history - indigenous folks and Black folks - have the worst infant mortality rates and the worst health outcomes.”

The proof is in and around the healthcare field.

Racial segregation points to infant mortality, Hardeman said, because the chances for an early, riskier birth increases. Minnesota is one of the most segregated states in the country, thanks in part to racial covenants that stopped people of color from buying homes. She also found that more run-ins with the police increase the chances for an early birth, which puts over-policed communities of color at greater risk.

The gap is so huge that Duke University says Black women with a PhD are more likely to lose their infant than white women who haven’t finished high school. It makes the issue personal for Hardeman, who has a 7-year-old daughter.

Hardeman believes that policies which target housing disparities, public safety and racial bias can address the gap in infant deaths. There has been some progress on that front: A bill that proposes to study maternal health and require anti-racism training is moving through Minnesota’s House of Representatives. Still, Hardeman has her doubts.

“The fact that we have been tracking infant mortality rates since the 1800s or even earlier and we still see this gap makes me wonder, ‘What will it take?’” Hardeman said. “We have a responsibility to care for and protect our young and our vulnerable… If we can decide that every Black infant that comes into this world is valued, and make sure that we’re doing all that we can to ensure that they have a life where they get to be healthy and thrive and grow up in a safe place in a safe environment - and have what they need to thrive - that’s community health and wellbeing for everyone.”

Pollard is doing what she can to make that kind of change. She supports other friends and mothers who lost their children, and shares her story with them. She hopes that people find peace in hearing about her journey, and realize that they are not alone in this.

“Some people, they lost their child[ren] to SIDS twice. And some people lost their children to miscarriages,” Pollard said. “You’re not the only African-American woman. You’re not the only mother that has lost a child. If I could do it, I believe that you can do it.”

It’s now been two years since Pollard lost Dayana. Through therapy, doulas and support from others, she has been healing. Now when people look at Ivory’s full head of hair and say she looks just like her sister Dayana, Pollard can smile. It's likely that many mothers in Minnesota cannot do the same.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

In a year that has proved to be a turbulent challenge for so many Minnesotans, the Black church has continued to serve the spiritual and health needs of its congregants of color. The Stairstep Foundation’s CEO Rev. Alfred Babington Johnson shares some of the ways in which the state’s Black churches are working together to provide shelter in what has been an onslaught of storms.

Black people and people of color in America have been subjected to centuries of medical experimentation and abuse, a history that has spurred mistrust of the healthcare industry for generations. Discover how some Black doctors are addressing the legitimate concerns of their patients of color who are deeply skeptical of the COVID-19 vaccines.

To demonstrate the healing power of therapy, Sanni Brown-Adefope agreed to attend a recorded session and explore the trauma that has affected her life. Dr. Sheila Sweeney, of Peaces ‘n PuzSouls, partnered with Sanni to take her through a healing reflection of her past. Dr. Sweeney is a psychotherapist with a special interest in the mind, body and soul connection. In this session, she demonstrates a multitude of ways that connection emerges as someone is allowed to speak their own story.