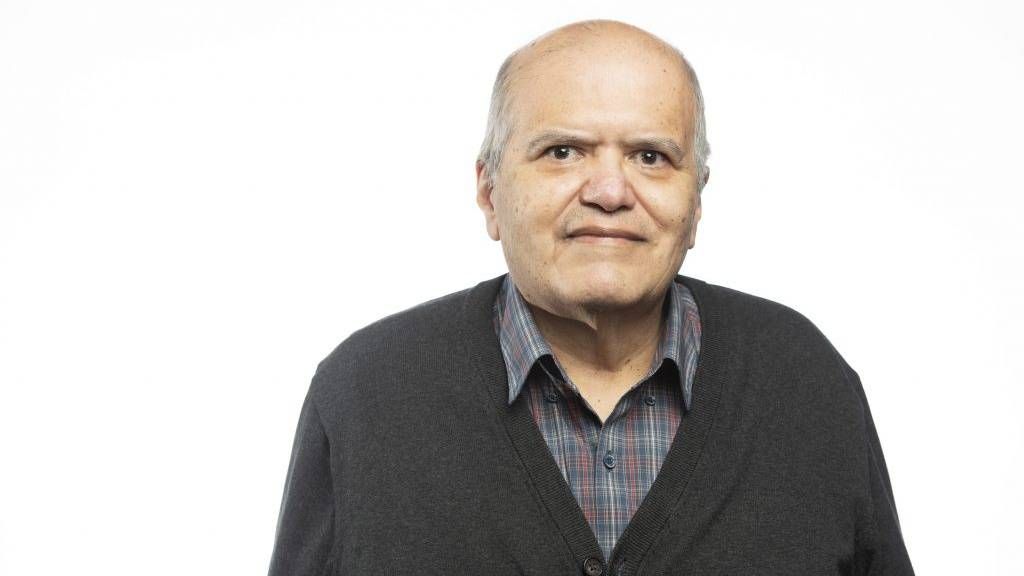

Poet Ray Gonzalez Shares "The Language of Sunlight, 1956"

THE LANGUAGE OF SUNLIGHT, 1956

My transformation from speaking my native Spanish to the necessity of English happened when I was five years old. Until then, I spoke only Spanish at home, even though my parents were bilingual and I heard them speak English. My grandmother Julia, who raised me during those years, could not speak English. Spanish was what I heard all day. My memories of Saint Mary’s Catholic Church in downtown El Paso are filled with the strange cruelty of the nuns and how I learned my first words of English.

The nuns beat kids on the head with yardsticks. If you got caught chewing gum, it would not go on your nose like it did in public schools, but got stuck to your chin. As time went on in the hot classroom, the gum would hang farther down until the student was told to remove it with a Kleenex and throw it away. The nuns' first job was to make sure no one spoke Spanish in the classroom, in the cafeteria or on the playground. Speaking Spanish was against the rules and punishable by a beating with the paddle, the whacking sound and cries of the kids followed by the screeching of the nuns, “English only! Do you hear me? English only!” Whack! A few hard blows on your rear and off to your desk. Kids sat at their desks, tears streaming down their faces, trying not to sob aloud because any sound meant one more swat. I never got caught because I was too shy to speak to other kids and couldn’t communicate with them because I didn’t know English. When I ran into my cousin Benny, who also went to school there, we whispered to each other in Spanish.

My kindergarten teacher was Sister Irene, and she was a tall, thin nun who reminded me of a stork in the picture books we were given to read. She loved to move the kids around the room all the time. We would be assigned a certain seat, memorize the desk we were to occupy, then she would scramble the seating chart the following week. She never stopped shuffling us around.

That day, we had been studying the eight basic colors. Sister Irene divided the class of 32 kids into groups representing each color, with four of us per color. She had eight huge poster cards painted in the various colors, with the name of the color under each square. When she called my name, she held up the red card. I managed to understand what Sister Irene wanted us to do as we sat quietly at our newly assigned seats.

I was in the desk closest to the hallway door. The Sister instructed us to stand when she held up our color card. As she held green, the four kids assigned that color had to rise and repeat the color. We started this game at the end of the school day. Some of us had to catch buses to get home, often miles away from downtown. Sister Irene told us to sit quietly, so we could begin. She spoke good English.

Sister Irene held up the orange card. Four kids stood by their desks and repeated the word “Orange” together.

“Very good, Samuel. Yes, Leticia.” The Sister repeated the name of each group member as they answered. She held up green and the group stood and answered, “Green.”

Anticipating my group’s turn, I gripped the edge of my desk and stretched my neck to look at the color cards. This was weeks before my parents discovered I needed eyeglasses. My anxiety grew because the red card had not been held up yet. The final bell was going to ring in five minutes.

I nodded in silence. There were three colors left, including red. Sister Irene held up the blue card and I quickly stood with the four kids in the blue group. Laughter broke out across the room, jeers and calls against me growing louder. I was frozen by my desk and could not sit down. Sister Irene’s menacing look shocked me and caused me to sweat.

“No, Ramon! You are in the red group! Red!” She yanked the red card from her lap and showed it to me. When the laughter died down, she said, “Ramon, you stay after school until you learn your colors. Sit down.”

Dizzy, I almost fell into my seat. I did not know what the phrase “Stay after school meant,” though I sensed it was bad. I had never stayed after school before and would miss my bus. My older cousin would not wait for me. The Sister held up the yellow card after the blue. I watched the four kids get up through my tears. I whispered, “yellow.” The final card was mine and I stood and croaked the word “red” with my group.

Suddenly, the bell rang and startled me. Students grabbed bags and coats and headed for the door. The Sister was surrounded by dozens of excited kids and did not see I ran out the door and across the schoolyard in terror. I found my cousin and we boarded the bus. It pulled away with no nun after me.

I had to go to school the next day. I got on the bus that morning in a frightened daze. Nothing happened. The Sister forgot she told me to stay after school. She forgot my mistake of standing on the color blue. As I made it to the final bell, I pulled out my box of eight crayons and recited the eight colors. I held the crayons in one hand and turned to Benny. He stared at me as I said, “red, blue, green, purple, brown, black, yellow and orange.” They were my first words in English.

Q&A WITH RAY GONZALEZ

Where did you grow up, how did that influence your work?

I grew up in El Paso, Texas, that area of cultural conflict that is constantly in the news. The clash of cultures on the U.S.-Mexican border and its powerful desert landscapes have given me a lifetime of things to write about.

How did you get into poetry? Why did you move to Minnesota?

I had a wonderful college teacher in El Paso, the late Robert Burlingame, who opened my eyes to poetry by teaching me that poetry is for everyone with its universal subject matter.

Describe your work to someone who hasn’t seen it before.

My poems are about the stark beauty and mystery of the desert southwest and about Mexican-American family life. My poems combine the natural world with life in a highly politicized region of the U.S.

What is your artistic process?

I read constantly - poetry, history and fiction, and they influence what I am thinking as I take notes. With poetry, I keep a notebook for ideas and responses to daily life. When I have enough, every few days, I go to the computer to write poems.

How do the themes of migration and immigration come into your work?

They are the grand subjects of history and the lives of people everywhere. The border region is a monumental and dramatic stage where different people both join and resist each other, in order to find a home. Grand historical forces are shifting constantly across the desert, and it is up to the writer to witness and recreate them on the page.

Why do you keep coming back to these subjects?

I keep going back to these subjects because the desert southwest is my home, and I believe all writers must deal with home so they can triumph artistically and keep evolving as writers. There are many stories to tell.

Where and what do you teach?

I am an English Professor, and teach creative writing and literature in the MFA Graduate Writing Program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

How is teaching influenced your work?

I learn from my students because they are writers, too. I guide them through what I have learned after 50 years of writing, and they plant me in the modern world through their own point of view.

How has your art changed you?

Poetry makes you see the hidden things in daily life.

What do you hope audiences get out of your work?

I hope they sense that poetry is for everybody and not just for those who write it.

Describe the work you’re performing for Art Is.

The theme will be migration, immigration and a search for home.

How has your identity shaped your work?

You must be a quiet, perceptive individual to be committed to poetry.

As a well-known and published poet, how do you see your role changing?

I draw more on my teaching experiences and watch patiently the growth of my students.

What is the role of the poet in the community?

The role of the poet is to encourage the gift of the imagination we are all born with.

See more stories from our multi-media series Art Is…

Trained at the foot of the great song poets of his time, song poet Bee Yang has lived his life as a refugee of war, toiling away in the factories of America. He shared his art as part of his daughter, Kao Kalia Yang's, Art Is...Our Call for Peace cohort in 2019. No matter the primary language you speak, prepare to be amazed by his craft.

When you think of spoken-word artist Tish Jones, know that she is somewhere dismantling age-old systems of oppression, putting on for Hip-Hop culture and creating new art to move the conversations forward. Jones was the curating artist for the April 2019 event, Art Is…My Origin. Art Is… My Origin is a sneak peek into the most sacred of creative spaces – home.