On edge, Minnesota remains the stage for race relations in America

This dispatch is part of a series called On The Ground" with Report for America, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project.

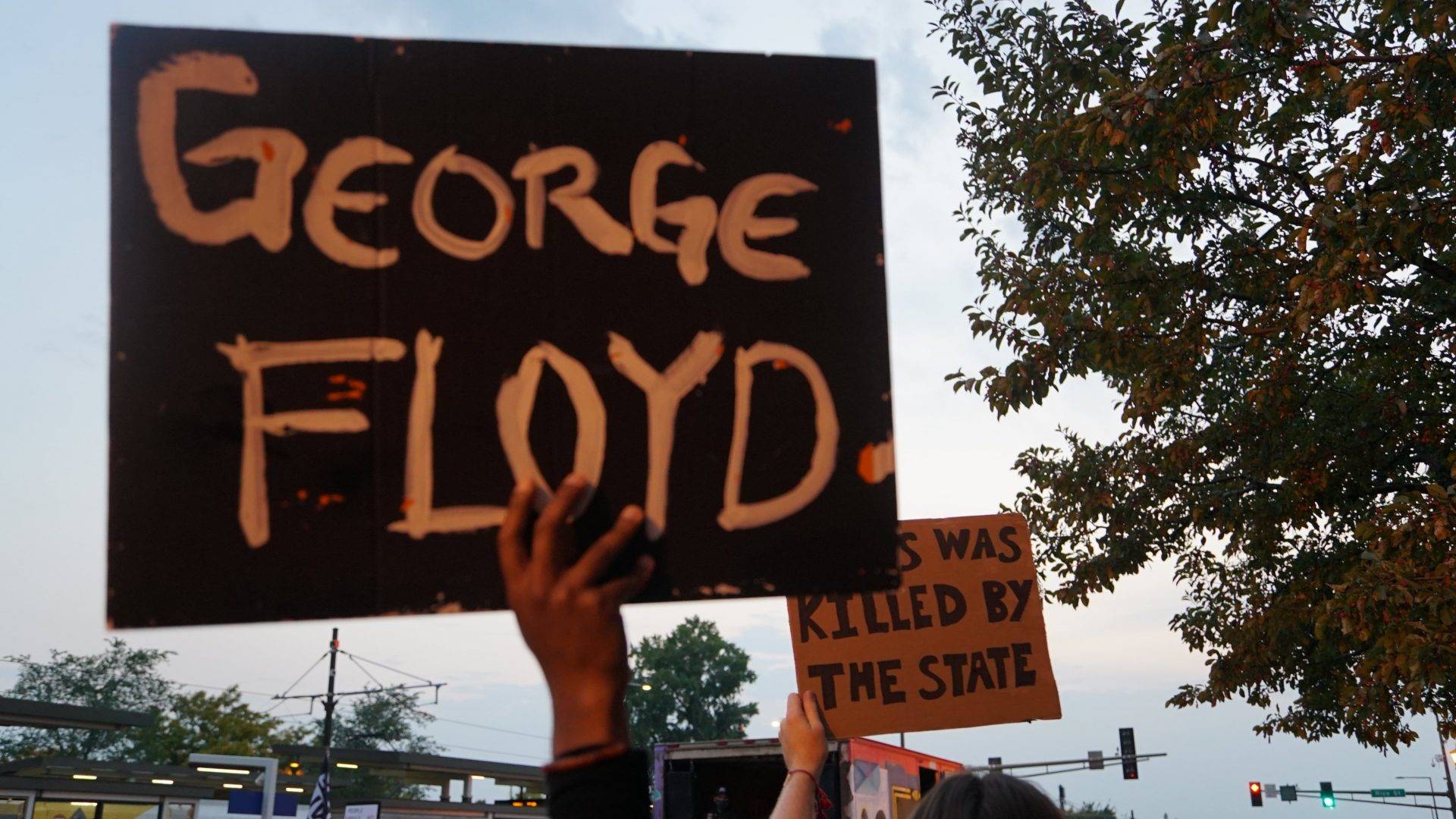

It was July at the intersection of Snelling and Minnehaha Avenues, months after George Floyd died under the knee of a police officer, choking "I can't breathe" at another local intersection.

The midday sun beamed as passing motorists rubbernecked to watch the scene unfold: a white police officer pulling over a Black man. A bicyclist, reaching into his pockets as if for a phone, nearly crashed as his eyes locked onto the officer.

Each passerby was a potential spectator to a scene that, on Memorial Day in May, was burned into the national psyche.

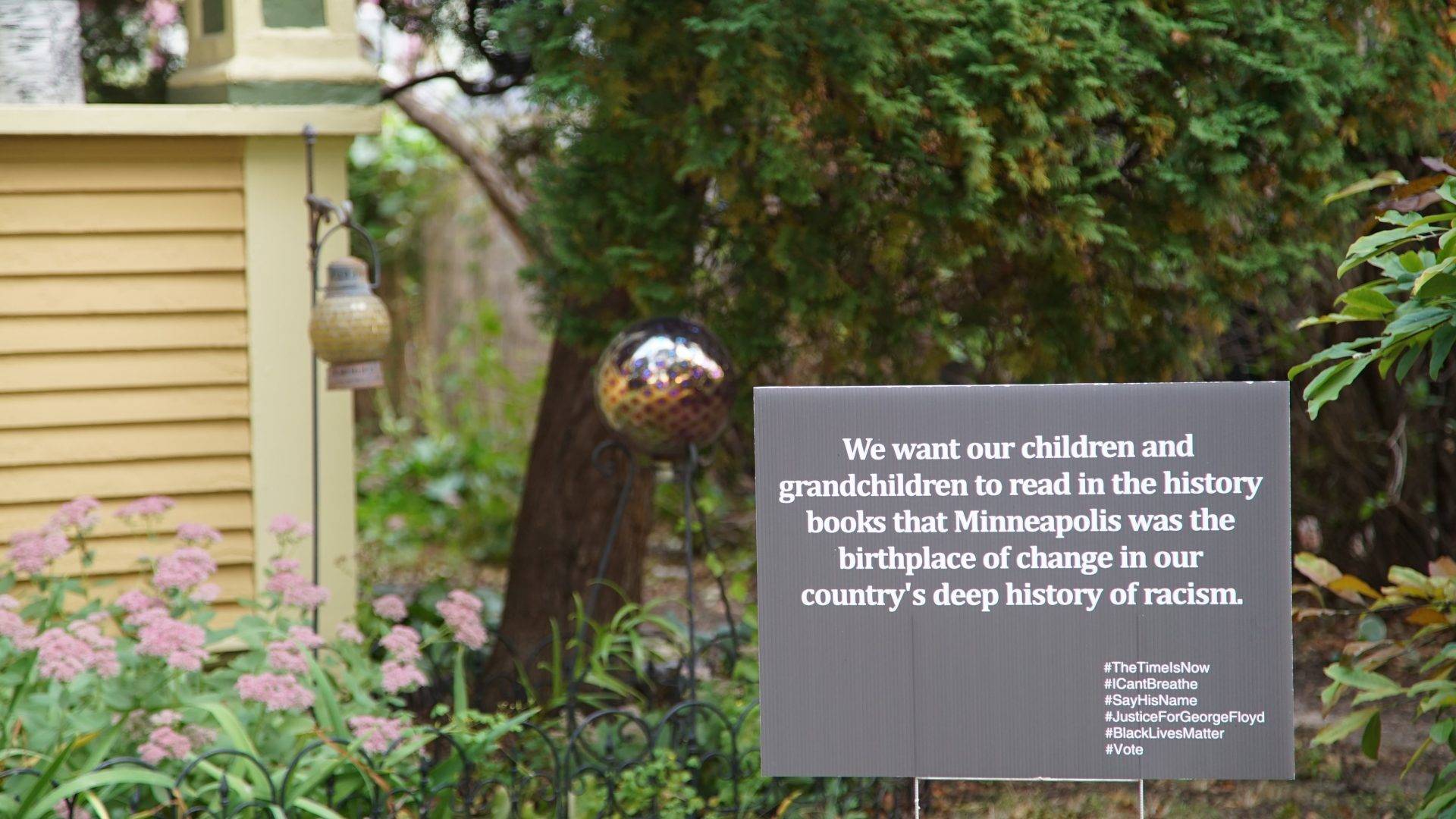

Since that indelible event, marches across the nation called for an end to the over-policing and use of excessive force against Black Americans. Many of the most sustained protests are now focused in Portland, Ore., and Louisville, Ky. In the Twin Cities, where it all started, the flames of protest have cooled — but fear of losing another Black life remains palpable.

"The state of Minnesota and the nation, and frankly the globe, needs to see an example of a criminal justice system that works for the people in our state," said Justin Terrell, executive director of the Minnesota Justice Research Center. "And everyone's watching."

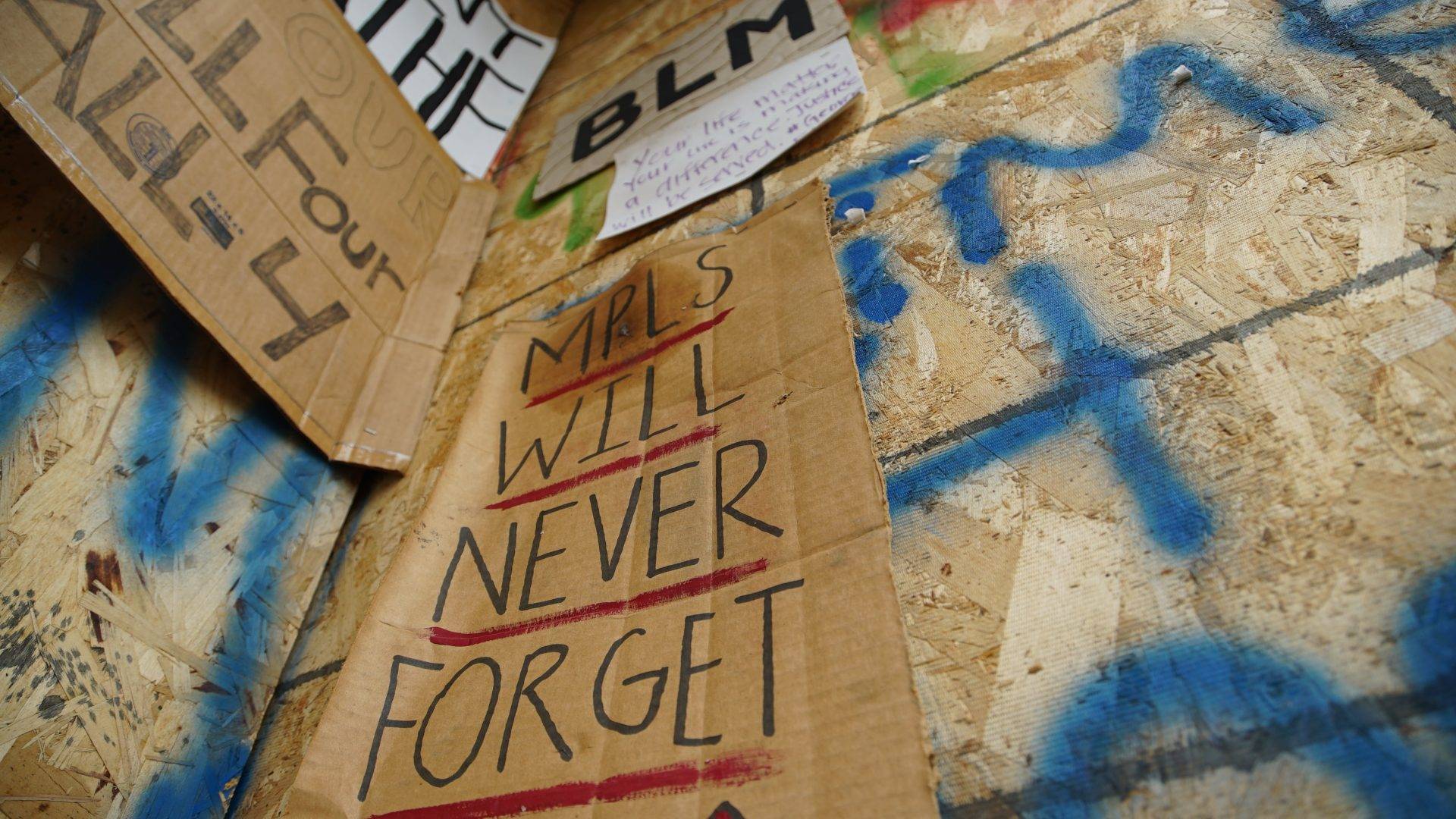

Mementos of civil unrest pepper the walls of buildings and storefronts. Plywood boards still cover broken windows of some shops. Signs reading "George Floyd" and "Black Lives Matter" are spray-painted across Lake Street. A database at the University of St. Thomas has catalogued more than 1,300 similar graffiti and murals in each U.S. state and 76 countries. There are fewer protests, but more tense moments like that traffic stop.

For Terrell, who learned about criminal justice while advising Minnesota legislators as part of the Council for Minnesotans of African Heritage, Floyd's death stirred personal change, most acutely summarized by his five-year-old son: "Are those good police?" his son asked him.

"The stakes are high. Not for fear of a riot. The stakes are high because we need justice in our country," Terrell said, noting that tension is especially thick in the state's criminal justice system. "We have a justice system that was built in the shadow of the worst and one of the most egregious forms of slavery the world has ever seen … Until we understand where we come from, it's really hard to understand what's at stake here."

Minneapolis Police Department leaders understand the heightened stakes with each police interaction but they also have their own issues, said Chief of Staff Art Knight, who monitors community outreach at MPD and trains recruits on how implicit bias affects them.

"We've got to play the hand we're dealt, and right now there's a lot of anti-sentiment towards law-enforcement," Knight said, adding that decreased support from elected officials has officers on edge. "Even legit[imate] situations when officers do have to deal with someone, I can see some of them hesitating right now about using force, [thinking] 'Am I going to be second-guessed?'"

Officers who use force are required to wear department-mandated body cameras when possible, otherwise they could be fired. Knight said nobody there wants bad officers, but they are struggling with an ebb in community support and a surge in violent crime.

That stress has translated to how police respond to, and cope with, crime. An MPD analysis found that their response times have slowed, and around 200 officers have filed for disability — with many citing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Knight was demoted to the rank of a lieutenant after he used the expression "same old white boys" in an interview with Star Tribune about the lack of diversity in the department's ranks. He was referring to the need for the agency to rethink how it recruits, trains and promotes people of color and women. Knight, a Black officer who joined the Department in 1991, was demoted by Chief Medaria Arradondo, who is also Black. Some faith leaders and other community members have come out in support of Knight saying the officer is not wrong for speaking the truth.

Everyday citizens are feeling stressed, too. On average nearly a third of Minnesotans interviewed by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2020 reported symptoms of depression or anxiety most of the day. More people of color, an average of 39%, are experiencing such symptoms. Trahern Crews, a member of Black Lives Matter Minnesota, said one cause is systemic racism, which creates stress in the community. But Crews said the added stress has also mobilized more people to take action.

"Even amongst Black people who are law enforcement, who would always defend the police's position, are starting to realize that there has to be some change," Crews said.

Many are debating what that change would look like. Major grassroots efforts to help write that formula have fallen short. Less than half of a cohort of Black women running for office in Minnesota advanced past their primaries, and community-led pushes to reform the police might be going nowhere. But some of the more significant conversations are happening between church pews.

In 2018, Hans Lee began preaching at Calvary Lutheran Church, a block from where Derek Chauvin would kill George Floyd.

The church was thrust into the fray two summers later, becoming a medic station during the protests and sustaining the community through a food shelf. Cavalry members worried white supremacists would target them at first, but that worry shifted towards questioning their role.

"[It's] a tension around how best to do this, how best to support what's happening. To not become the focus of this because it really isn't about Calvary. It's about this community and this city and the greater cause of racial justice and ending police killings," Lee said. "The big question is, 'Will this moment pass us by?'"

In North Minneapolis, where most people of color in the city – 18% – live, Sanctuary Covenant Church Senior Pastor Edrin Williams and his congregants are discussing solutions to racial injustice. Some have suggested reforming the state's systems. Others have proposed tearing them down. But with some members' hope faltering after news that officers who shot Breonna Taylor would not be charged for her death, Williams is advising people to draw inspiration from history.

"There's never been a time where this country has treated us the way we need to be treated, but we've never taken it lying down," Williams said, comparing the struggle to the biblical story of David and Goliath. "Even if it doesn't happen in our lifetime, I think it's still worth it, everyday, to fight against these systems and seek to overturn them."

If Minnesota is the underdog fighting a Goliath of systemic racism, then America is its spectator. The police-involved deaths of George Floyd, Philando Castille and scores more people of color here serve as a microcosm for disparities that have long-existed across the nation. How the "Star of the North" reacts now could become the blueprint other states follow.

"We've got to learn to live together as brothers or we'll perish together as fools," Terrell said, quoting Martin Luther King, Jr. "Once we start to realize that our liberation is truly bound together, we can build a conversation across politics, across vocation, and really start to talk about what we need our justice system to do for the people."

Saint Paul's neighborhoods of color have a disproportionate number of vacant buildings than areas primarily occupied by white residents. That fact has a direct impact on crime rates, public-health risks and quality of life. Data reporter Kyeland Jackson examines the links between vacant properties and the city's racial disparities.

Alberder Gillespie was motivated by the police killing of George Floyd and led a charge of 40 Black women to run for office. While she didn't win her primary, she is committed to staying the course to advocate for change in the face of systemic racism and to wake Minnesotans up the to power of the Black vote.

A surge of minority voices has responded to the police killing of George Floyd. In the weeks since Floyd uttered, "I can't breathe," as ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pressed down on his neck, a new collective of individuals is taking action by running for office, engaging in politics and stirring change among youth. But is the momentum a movement or a moment?