Motivated by Racism, One Black Woman Plans to Change Minnesota Politics

Alberder Gillespie sat on a bench outside of the Minnesota State Capitol and told me how she left the South to experience a new kind of racism here.

An Aberdeen, Miss., native, Gillespie’s parents thrived in an era of segregation and Jim Crow Laws. Family and friends instilled strong values that she draws on today - like integrity, a duty for civic engagement and education. Gillespie felt she could be anything she wanted to be there - a mindset that we shared, thanks to our southern roots - but that changed when she moved to Minnesota.

“I lived out in Oakdale, which is really close to Woodbury, and it was just strange for me because people would stare all of the time,” Gillespie said. “I was like, ‘I’m living in a place where I’m not supposed to live - where they’re not accustomed to me.’ … I never felt that in Mississippi.”

A Purdue University degree and her husband’s work as an engineer did not stop the stares, or the feeling that she was unwelcome. Disparities she has since seen and felt have motivated Gillespie to engage in politics for nearly two decades. George Floyd’s police killing pushed her to be more active and lead a charge of 40 Black women to run for office. Gillespie didn’t win her primary election earlier this year, but she is positive that the initiative has set the stage for her next task: waking Minnesotans to the power of the Black vote.

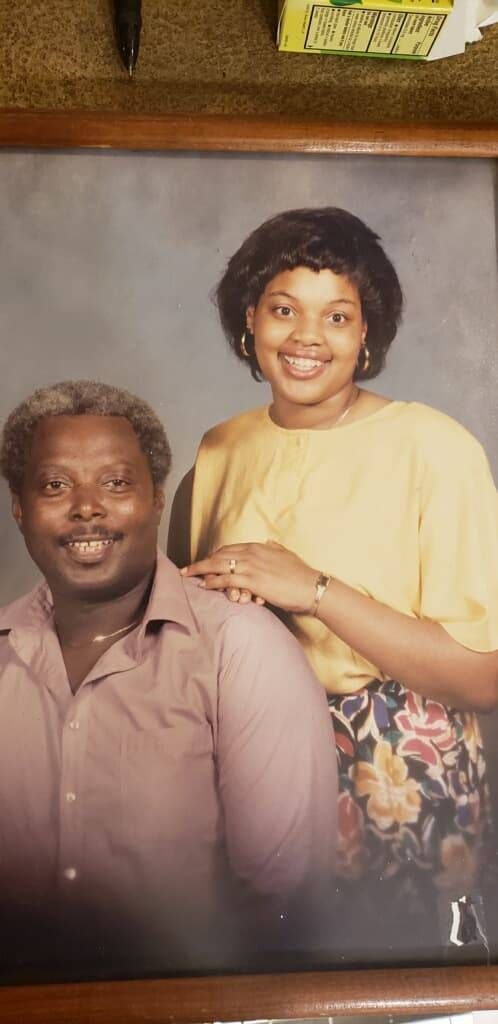

The Hamptons

Melvin Hampton worked all his life to provide for his mother, his wife Mary and for his daughter Alberder. Hampton started working at the age of 12 and experienced overt racism while growing up in Mississippi. Literacy tests, poll taxes and other measures were used to disenfranchise Black voters, and violent acts like the lynching of 14-year-old Emmet Till happened nearby and not long ago. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Movement and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 when major progress was made toward ensuring voting rights for Black residents.

Hampton fought against oppression in his own way. He lobbied for union workers’ rights and for the community’s needs. Eventually, he and his wife, Mary, would run for office. The Hamptons preached the importance of voting and civic engagement to everyone around them along the way, and Alberder absorbed it all.

“A lot of what I do now, I realize, it comes from what I saw them do. It comes from the beliefs they instilled in me,” Gillespie said. “[Dad] believed so much in the power of the vote. It was like a sin not to vote … He’s a really important figure in my life.”

He died in 2015. And on Father’s Day, Gillespie dedicated her run for Congress to him.

When Gillespie moved to Minnesota 27 years ago, she relied on the values that family taught her while growing up in Mississippi. She arrived looking for opportunities, but the "Star of the North" taught her that some people treat darker skin differently.

The Veil

Racism attacks us Black Americans in the disguise of a different mask every day.

As a Black man from Kentucky, it strikes when white people cross the sidewalk to avoid me. It motivates security to follow me through retail stores. It urged officers to pull me over for a traffic stop and to ask if my car belonged to me. For Gillespie, racism also attacked in the guise of an officer at a traffic stop.

It was the mid-90’s, and Gillespie was a regular church attendee in Saint Paul. She was driving the church van one day when police stopped her for running through a stop sign. Gillespie apologized and said that she did not see the sign because tree overgrowth blocked it from her vision. That officer accepted her apology, asked for a driver’s license and told her to get in the back of his squad car.

He gave no reason for making that request besides running her license, and when she asked again why she must sit in his car when she had done nothing heinous, he answered by ordering her, again, to get in.

Gillespie cried in the back of his car. The officer, she said, held back laughter.

“He thinks it’s so funny. I don’t even know if he ran my license, and then he’s just like, ‘You can get out.’ [He] never gave me a ticket,” Gillespie said. “That was entertainment for him, and that’s when I was like, ‘This is what people are subjected to here in this state.’”

Racial disparities became more evident to Gillespie after that. She would soon understand that racism in Minnesota is tucked behind a veil that is stitched in the fabric of the state’s systems.

JIM CROW OF THE NORTH REFERENCE

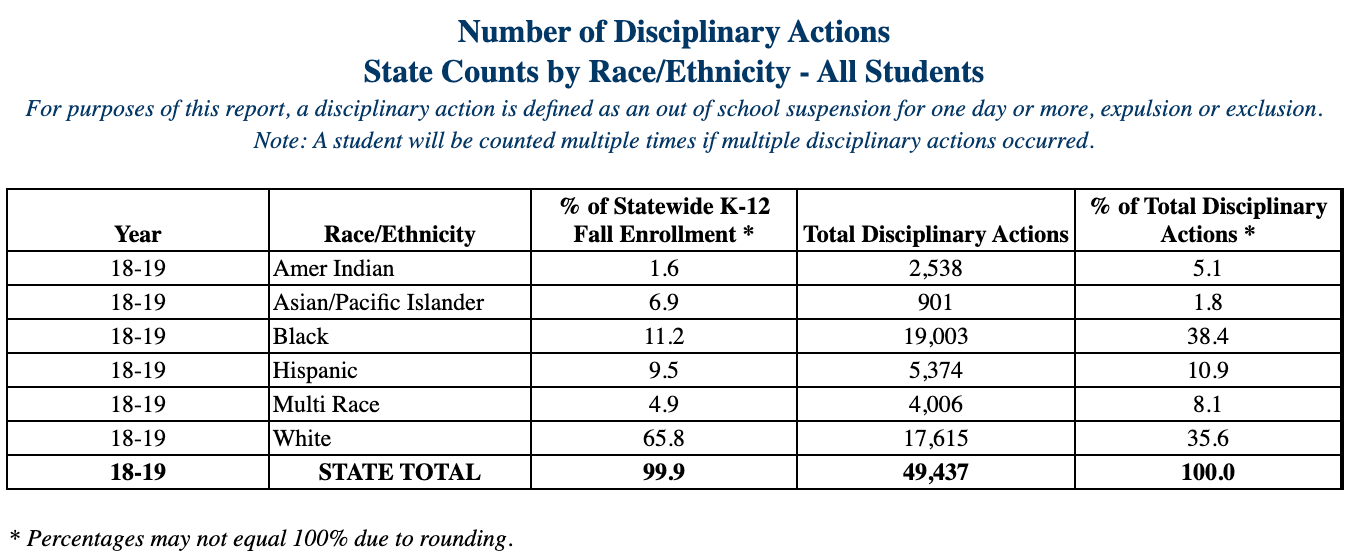

Black people comprise just 7% of Minnesota’s population, but are 5.4 times more likely to be arrested for using marijuana than white people, even though both groups use it at similar rates. Black adults in the state’s criminal justice system are imprisoned at 10 times the rate of their white counterparts. The percentage of minority-owned businesses in Minnesota is well below the national average. And in education, where Black students form 11% of the kindergarten through high-school population, Minnesota punishes more Black students than white. It also ranks last in the nation for the percentage of Black students graduating high school on time.

Gillespie said educators put reputation before students’ well being and that police treat youth near her like criminals. So when she was asked to leave her school board position to be a Senate district vice-chair, Gillespie took a chance - and began to deploy all the values and political know-how that her parents taught her. But barriers exist in politics, too.

She and other women of color were repeatedly told they should not run for office or that they could not win, and Gillespie said many politicians have forgotten the Black community because many do not vote. So platforms targeted at helping Black people have been shelved, and the community has suffered for it.

“Every term that [politicians] decide that’s not your priority, somebody’s paying a price for that,” Gillespie said.

Too often, that price is paid with our lives.

A Seat at the Table

No matter how many videos we watch, seeing other Black men and women die on camera feels traumatic, moving and personal. When I watched a video of police killing 12-year-old Tamir Rice, I thought of my cousin. I saw my brother’s face in news coverage of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, who was shot 16 times while walking away from police. And when an officer shot and killed 43-year-old Samuel DuBose as he drove from a traffic stop, I thought, ‘That could have been me.’

When Gillespie sees such videos, she thinks of whether her children could be next. So when George Floyd cried for his mother, Gillespie and members of the Black Women Rising group she founded said, ‘Enough is enough’ and ran for political offices.

“If we’re not at the table, we’re on the table. We are tired of being on the menu,” Gillespie said. “If we want this to be more than just a moment, we have to put people in place who will make decisions that will impact us all in a positive way.”

Gillespie did not win.

Less than half of the 40 Black women in Minnesota running for office this year advanced past their primaries. But, she says, they succeeded in raising awareness about issues affecting Black voters and teaching local leaders that they can no longer discount her community. She plans to build on that momentum by getting more Black voters civically engaged, hosting conversations between elected officials and unheard constituents, and by building a support network of Black professionals to help future political candidates. Despite how she and others fare politically, Gillespie says they are not going away.

“We may have 40 this time, [but] we’ll have 80 next time, or we’ll have 100, until we get what we want,” Gillespie said. “[Women] are ready for change, and when a Black woman has her mind made up - we’re going to make it happen.”

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

In 1969, University of Minnesota students staged a 24-hour protest in Morrill Hall to fight for racial justice on campus. Their demands were specific: the support of Black students through scholarship funding, student support services and the creation of an African American Studies department. Get inspired by their fight and its lasting impact.

A surge of minority voices has responded to the police killing of George Floyd. In the weeks since Floyd uttered, “I can’t breathe,” as ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pressed down on his neck, a new collective of individuals is taking action by running for office, engaging in politics and stirring change among youth. But is the momentum a movement or a moment?

Danielle Swift has been on a spiritual journey from the front lines of a Black Lives Matter protest, to the campaign trail for Saint Paul City Council, and finally to a life of community organizing. She’s here to tell us how we can all become an effective activist for change, whether your call is to the front or to the back.