Love from Saigon, Minnesota

A love story remembering food, home and homemade Vietnamese food.

No one who meets me today would ever suspect that I did not prefer Vietnamese food when I was growing up. Today, I am a foodie gastronome and a scholar of Vietnamese cuisine, and even though I have an MFA in poetry and am also a professional writer and artist, I confess that I own more food and beverage books than poetry books - and in my small, studio apartment, I use a stack of Vietnamese cookbooks as a bedside table.

"So how did I come to love Vietnamese food?" you might wonder.

This journey of love is a layered one, akin to two rivers running parallel: a yearning to discover my Vietnamese roots, and a desire to better understand my parents and their painful pasts. As these two streams of soul searching converged into an ocean of historical and personal knowledge, I came to love myself and my heritage almost as much as a spicy bowl of homemade phở.

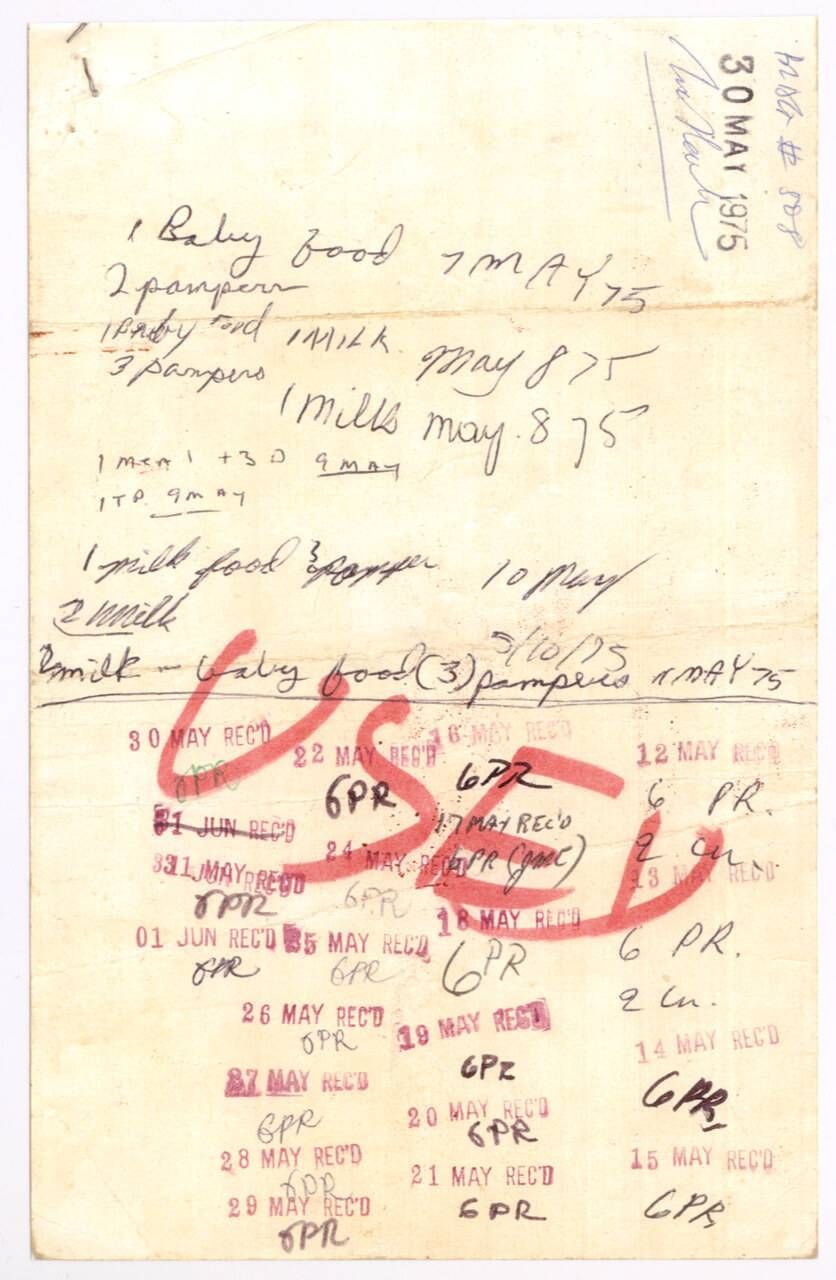

My story begins in April of 1975 in Saigon, Việt Nam, a few days before the fall. As the "American War" or War in Việt Nam and South East Asia came to a catastrophic end, my family - father, mother and six older siblings - fled with the assistance of the US government to a relocation processing center in Guam. When we entered the U.S., we were then held in a refugee camp at Fort Indiantown Gap in Lebanon County, Pa. At the time, I was only nine months old, and during my family's evacuation, I was given baby food and milk because my mother, along with the rest of my family, was malnourished. My feeding schedule was noted on a government card that my father held onto. This beige card was found only after his death – the earliest record of my having "American" food.

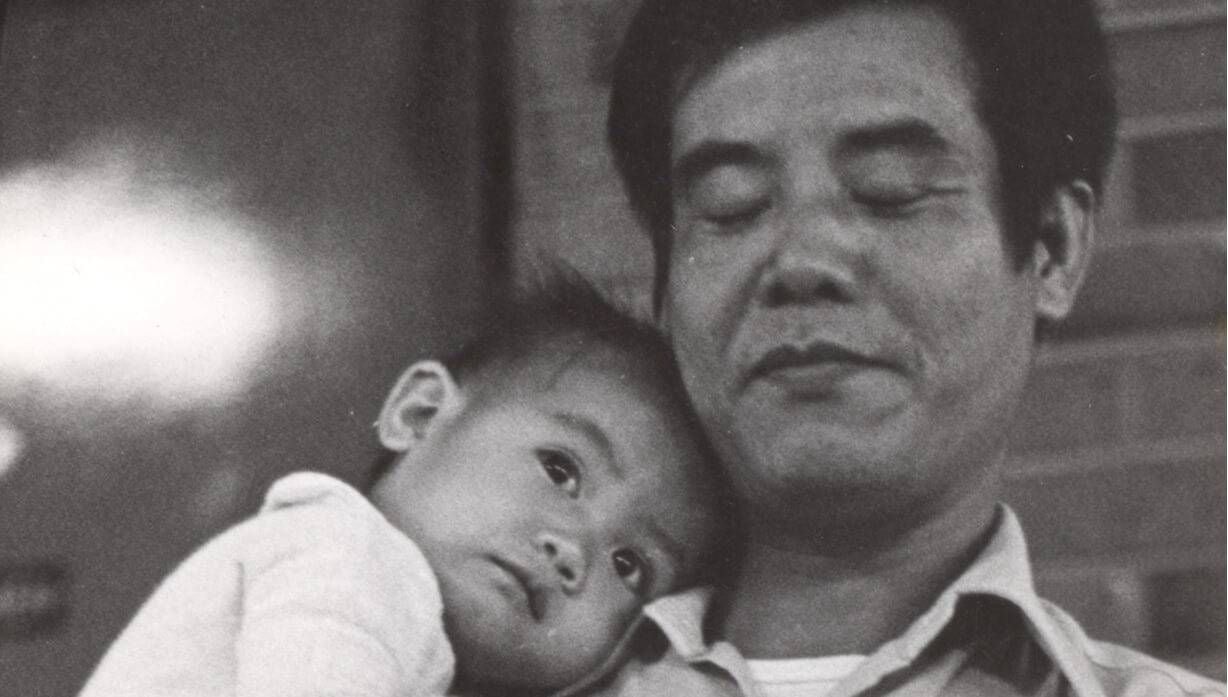

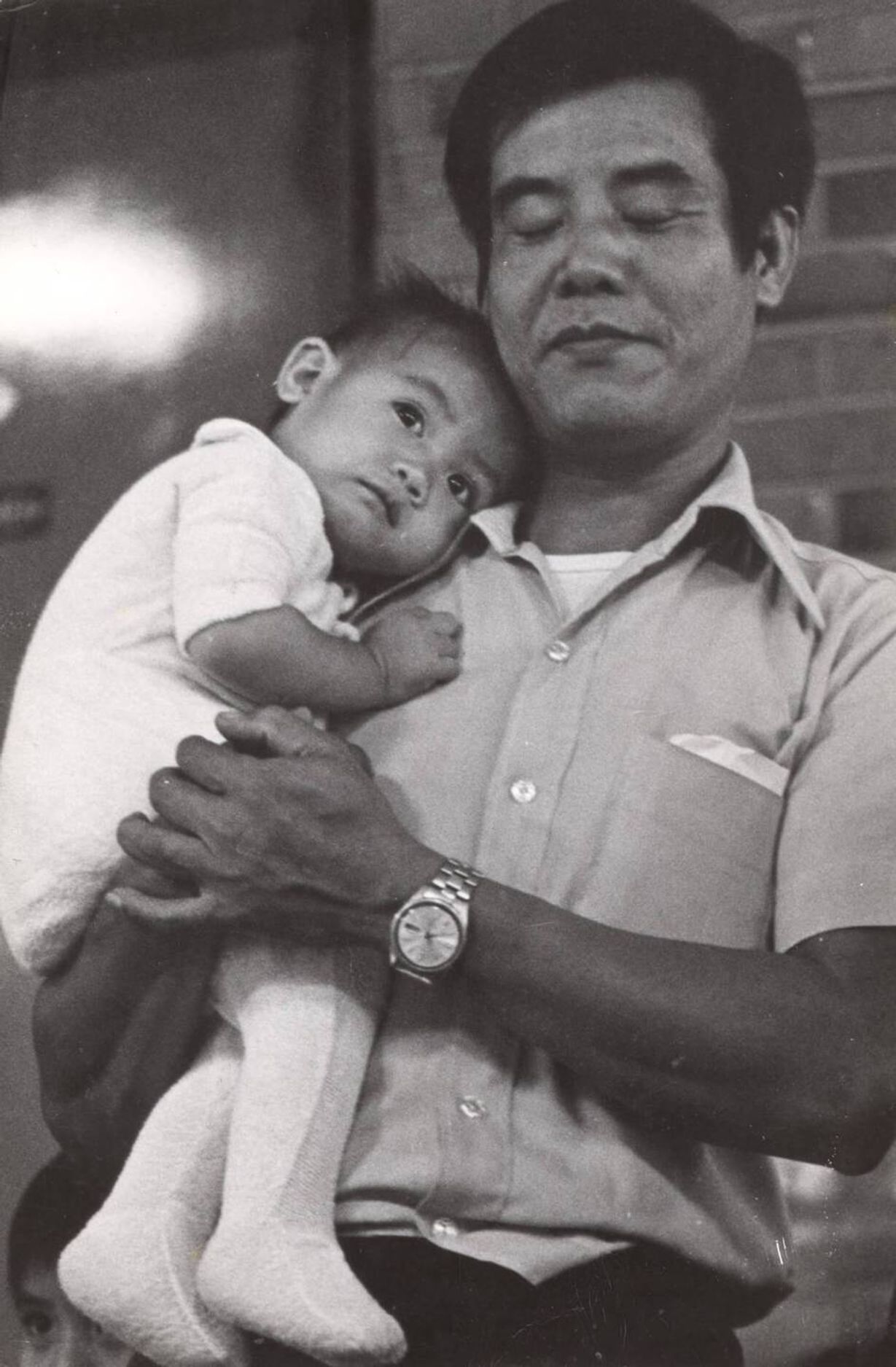

In the late spring and early summer of 1975, my immediate family, along with approximately 20,000 other Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees detained in refugee camps around the U.S., waited for months in anguish and uncertainty for a sponsor. Although many Vietnamese families made their way to warmer states in the U.S. such as California and Texas, a Lutheran Church in Little Canada finally sponsored my family. In July of 1975, we landed at the Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport. One of my most beloved possessions is from that day, a black-and-white photo of my father comforting me tenderly in the crook of his right arm – my head nestled on his shoulder – eleven-month-old eyes anxious, unaware of the future ahead.

The Lutheran church generously allowed my family, which was quite large, to live in the parsonage, and, by 1976, we were able to move into an apartment on Rice Street in Saint Paul, thanks to help from our social worker. By 1978, my family moved into our very own house, also in Saint Paul. My earliest memories of food are from this two-story, yellow-sided house with a front, glass-windowed porch, three bedrooms and only one bathroom for nine people, on the corner of Western and Nebraska in the North End neighborhood of the city.

As far back as I can remember, I was an extremely picky eater and ate mostly Cơm and Ruốc, a simple combination of steamed white rice and homemade, shredded and dried salty pork sautéed in caramelized nước mắm. This meat and rice staple is an all-time favorite of every child and grandchild in my Nguyễn family clan (and one of my comfort foods to this day). My older brothers can attest to my picky eating habits as a child since they were always the ones that were forced to finish the food I stubbornly refused to eat. I realize now that my picky eating probably had more to do with being a sensitive soul and wanting some control of my young, immigrant life, rather than a true aversion to Vietnamese food. But back then, my food preferences were limited and would later develop into an obsession with American food.

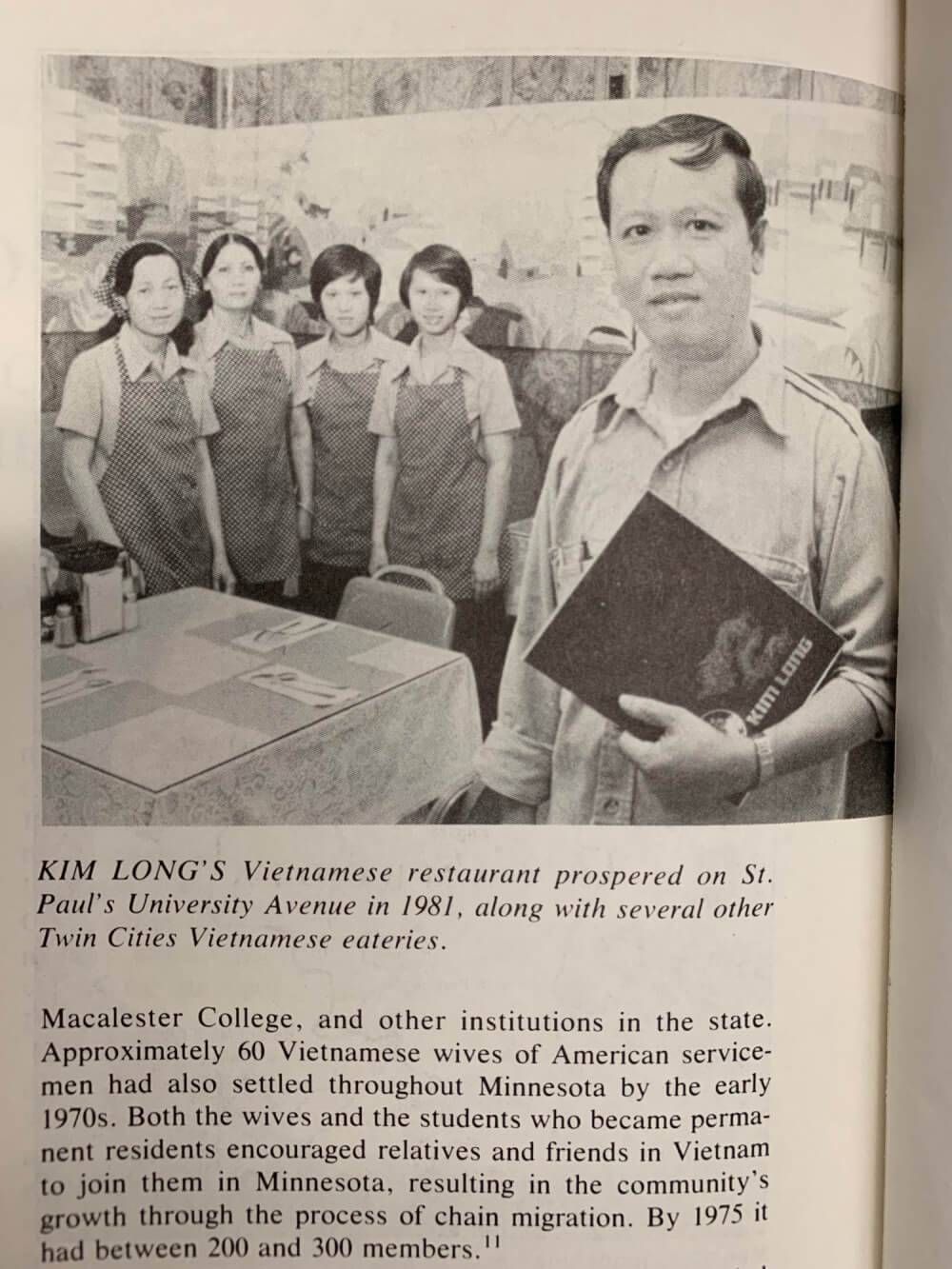

My mother was the primary cook in the house, and after a few years in the U.S., she started working as a cook at one of the first Vietnamese restaurants in Minnesota, Kim Long, which opened in 1978 and was located at 439 University Avenue in Saint Paul. My father, along with my mother, would work long days to financially support and feed their seven children. My family was very poor when we started out - when we arrived in the U.S., my father had only $50 in his pocket. Since my mother was not home when her children came home from school and returned home after they were asleep, she would leave a pot or pan of something on the stove that she cooked before going to work or after she got home from work the night before for us to eat. I think I often refused to eat her food, not because I disliked her cooking, but because I, as her con út, youngest child, missed her so much.

In those early days, I would sometimes accompany my parents on the weekends to the few Asian markets and Cub Foods stores where we bought our food. I was too young in the beginning to ask for any particular food, but as I got older and became too big to ride in the grocery cart, I would beg my parents for a few American food items like Goldfish Crackers and candy-sweet Corn Pops cereal. And because I was emotional, unlike the rest of my family (I blame this on the hormone/enriched dairy milk that I was issued as a baby), and was often ordered to withhold these emotions, I would sometimes cry when they would say no. I did not cry to manipulate them into buying me these foods (although they would occasionally break down); I cried because my Vietnamese skills were so limited: I did not have the words to express my feelings.

There is a particular agony that one feels when they realize but cannot articulate how different they are from the people around them. Even though my elementary school friends assured me that they thought of me as "white," I was painfully aware of how my reality at home was drastically foreign to that of my friends. It was not unusual to find my parents butchering meat on the floor of the kitchen or frying up large pots of sliced onions or stir-frying something spicy in garlic and fish sauce. It was humiliating when I was teased by my friends about the "stink" on my clothes, especially when I went out on weekends in high school. Their words scarred me and made me feel ashamed of being non-white. Throughout my youth, I experienced excruciating embarrassment because of my ethnicity and poverty, and I endured the torment of what W.E.B Du Bois called "double consciousness" in secret because I did not know who I could talk to that would understand. I was uncertain about which world, American or Vietnamese, I actually belonged in.

I am not sure if it was the subliminal effect of the hot, "free lunch" I ate every day until I graduated from high school - even to this day, I cannot eat anything cold for lunch, and the sight of tan tater tots and soggy, square pieces of cheese pizza takes me back to my years in public school - but I felt pressure to be "normal" like the white kids at school. I admit that I felt shame that my parents were refugees and could not afford luxury snacks like Fruit Roll-Ups or Capri Suns for my lunches. I soon came to adopt American ideals, not only in my food choices, but also in my identity, although that was not a conscious choice on my part. Growing up in Minnesota, the Midwestern land of white winters and white Scandinavians in the late 70's and early 80's of post-war America as an Asian girl was, to say the least, confusing and overwhelming.

Being Vietnamese was especially challenging because we were refugees of a country that was both the ally and enemy of a war the U.S. lost, or more accurately forfeited. Traumatized by being displaced from their homeland and the surrender of their country and family, my parents rarely talked about the war or shared their memories of their past lives in Việt Nam with their children. Both sets of grandparents and our entire extended family was back in Việt Nam, and the US military confiscated our luggage with our family photos. My parents were too poor and busy trying to financially survive to even think about emotional survival, and they did not have the privilege of "quality time" or "affection" with their kids. As the youngest daughter, I was too obedient and afraid to ask them all the complicated questions that came up for me as I came of age. What's worse is that, because my parents were rarely home and my siblings spoke only English with one another, I completely lacked the language skills to communicate with them.

When I became a teenager in the late 80's and early 90's, any effort to acknowledge my Vietnamese identity became even more challenging and complex. My father intentionally sent his children to a majority-white elementary school known for its quality education, and as a result, most of my longtime, close friends that I hung out with outside of school were white. It did not help that I, in addition to these "American" friends, knew nothing about Việt Nam or the war since it was never mentioned in school. They, too, claimed that their parents did not talk to them about the war.

How was I supposed to learn about how and why my family was in Minnesota? How was I to learn about my Vietnamese ancestry or mother tongue when my parents worked almost every day from morning until night? How was I to learn to cook and appreciate Vietnamese food when my mother was not around to teach me?

By the time I reached high school, most of my older siblings had moved out of the house to go off to college or graduate school. I was used to feeding myself after school and had practically done so since junior high. By this time, I was a master at cooking with a toaster oven, and my affinity for Vietnamese food was basically nil. All I was focused on (besides boys and Girbaud jeans) was getting good grades and playing sports so I could get into college. I wanted to fit in, and so I ate all the "trendy" foods my friends liked: Totino's Pizza Rolls, Steak-umm sandwiches, Banquet fried chicken frozen in a box, Swanson TV dinners, and Campbell's Chunky Steak and Potatoes and Sirloin Beef Stew canned soups. I can still feel the burning, oozing cheese of the pizza rolls on my tongue and the greasy, crispy batter of the fried chicken on my lips. Even though I wasn't eating a lot of Vietnamese food, I was definitely getting plenty of MSG in my diet!

They say that absence makes the heart grow fonder, but absence also makes the belly more appreciative. I learned this humbling lesson when I went off to college in 1992 at the University of Minnesota. I struggled at first, as the only non-white student in most of my liberal arts classes. I felt a pressure I had not felt in high school, a pressure that whatever I said was a reflection of what "all" Asians thought or believed. At least at Como Park Senior High School, there were other Asian students in class, admittedly mostly Hmong, but they were there. As my first year in college progressed, I began to feel isolated, not only in my classes, but also in the dorms and dining halls where they served only American food that was often bland and mass-produced. I will never forget the sad salad bars with only iceberg lettuce, the edges red from being left out too long and the shredded carrots flaked white by dehydration.

Ironically, I began to miss my mother's cooking, as limited as my palate still was then. As luck would have it, my mother was cooking at Chau's Restaurant on Washington Avenue in Stadium Village on the East Bank of campus at the time. From time to time, I would visit her, and although I would walk in the front door to the kitchen to see her, I would sneak out through the back door with take-out containers of chicken fried rice and stir-fried beef with broccoli that she had made just for me. Aside from broccoli, the only vegetables I would eat were potatoes and corn. I once picked out every pea and carrot from a large plate of fried rice.

After my freshman year in the dorm, I decided to move home to save money and gradually started to eat more Vietnamese food, which was, at this point, cooked by my father, who had been laid off by the data mainframe and supercomputer firm where he had worked for fourteen years since we came to the U.S. During my second year at the U of M, I was beginning to feel worn down by the passive-aggressive racism I experienced at school. I could not understand how I went from being "not Asian" to my high school friends to being "too Asian" for my college classmates. All I knew was that I was just trying to be "myself," but that self did not seem to fit in anywhere, least of all in Minnesota.

At the end of my sophomore year, I decided to transfer to Mills College, a private, liberal arts, all-women's college in Oakland, Calif., to finish my college degree. It was much more expensive and far from home. At 19, I chose to move to the San Francisco Bay Area because I needed to be around more Asian people, and I wanted to learn more about being Vietnamese from other Vietnamese people. I began to realize that the processed American foods I desired as a child symbolized an unconscious desire to assimilate to the processed culture and customs of America. The more I acquired a taste for Vietnamese food, which is composed of fresh and fragrant ingredients and usually made by hands and not machines, the more I wanted to learn about my parents' lives and all the things they lost and left behind.

Ánh-Hoa Thị Nguyễn is a refugee, poet, community artist and educator. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Mills College in Oakland, California. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Asian Pacific American Journal; the Vietnamese Artists Collective anthology AS IS: A Collection of Visual and Literary Works by Vietnamese American Artists; the Asian American Women Artists Association anthology Cheers to Muses: Contemporary Works by Asian American Women; Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora; "diaCRITICS," a project of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network; and the Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement. She has performed her work at numerous venues in the Bay Area and in the Twin Cities. Ánh-Hoa has completed residencies at Hedgebrook, a Writers-in-Residence Program for women, and has received a writing fellowship from the Elizabeth George Foundation and a Minnesota State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grant. She has also been the host for the Minnesota Humanities Center's "War and Memory" Series and a panelist for the Twin Cities PBS "Vietnam War 360" conversation series. In the summer of 2018, Ánh-Hoa was the artist-in-residence for The Floating Library with her project "Waves Enfolding: A Paper Memorial" that honored lives lost during the Vietnamese refugee waves of 1954 and after the war in Vietnam and South East Asia, 1975-1992. She is currently a member of She Who Has No Master(s), a collective of women and gender-nonconforming writers of the Vietnamese diaspora.

This story is part of the collection The Call to Serve: Stories of Sacrifice, War and the Way Home, which was funded by the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation.