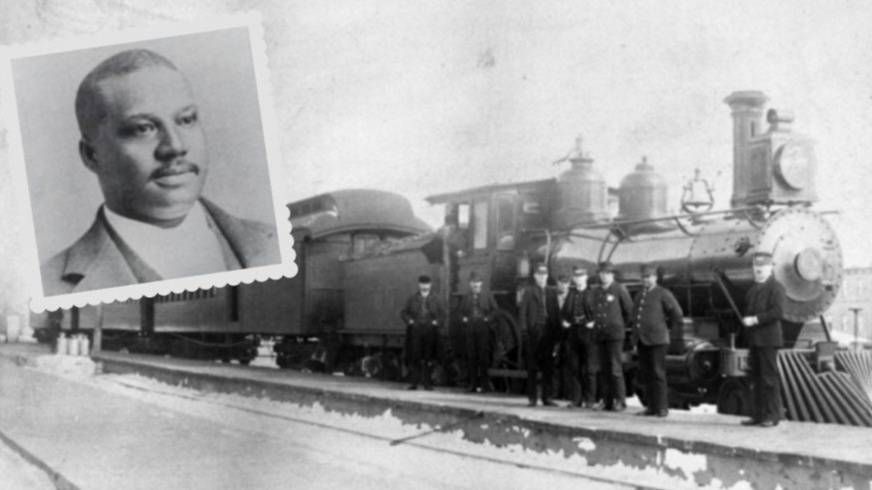

John Blair 'Kept Calm and Carried On' During The Great Hinckley Fire

“All I can say is that, on that awful night, I did what I thought to be my duty.”

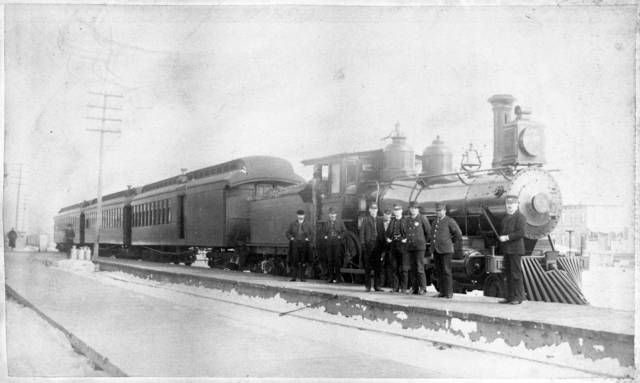

On Saturday, September 1, 1894, John Wesley Blair showed up for work on The Limited No. 4 train. The porter was familiar with the 170-mile route from Duluth to Saint Paul, where he lived with his wife Emma and their two pre-teen boys.

Not much is known about John Blair prior to this historic day. Born in Arkansas in 1853, Blair's job as a porter for the Saint Paul and Duluth Railway Company likely involved hauling baggage, cleaning the train cars and seeing to passengers' needs - which may have included everything from shining shoes to serving food and beyond. Like many Black men around the turn of the century, Blair likely found his work as a railroad porter to be a way to gain a steady income and a bit of upward mobility. But porters were also often mistreated, underpaid, overworked and subjected to countless indignities on the job.

As the train departed Duluth at 1:55 pm, Blair continued his work of making the nearly 150 passengers on the 7-car train comfortable. But as the train made its way south, the sky became increasingly dark. Unbeknownst to those aboard, two forest fires had merged down the tracks to create a deadly firestorm. A combination of one of the driest summers on record, extensive logging and debris, low humidity and blowing winds led to the start of what we now know as The Great Hinckley Fire. As the air became thick with smoke, Blair handed out wet towels to help passengers breathe.

Learn more about another major catastrophic fire that took place 24 years later in the WDSE PBS North documentary Fires of 1918.

One mile outside of Hinckley, the locomotive slowed to a stop as 150 people surrounded the train, begging for help. They had just escaped fires in town, and told those aboard that the bridge and station in Hinckley had burned down. Along with the rest of the train's crew, Blair helped these new passengers aboard.

In an 1894 account of these events translated from Swedish, one passenger noted that it was Blair who first mentioned the proximity of Skunk Lake. The engineer threw the locomotive in reverse, speeding five miles backwards to the shallow swamp known as Skunk Lake. As the train became engulfed in flames, the windows imploded. Blair continued to care for the passengers, encouraging them to get on the ground and stay calm, spraying their clothes with the fire extinguisher, and giving them water to drink and wet towels to wrap their wounds. Blair himself suffered severe burns.

Upon reaching Skunk Lake, the train's crew helped the passengers off the train and into the lake. Blair made repeated trips back to the train to rescue children. He was the last one to leave the locomotive once he was certain all passengers were off. Everyone remained in the lake until the fire lost its power and moved on. In the cold of the night, Blair helped passengers back to the charred remains of the train where they could stay warm.

In the early hours of September 2, a relief crew from Duluth arrived on a hand car to rescue the passengers. Today, a sign on the Willard Munger State Trail marks the location of Skunk Lake.

In the following days and weeks, the crew and passengers would come to learn that the fire had burned a quarter-million acres in just four hours. Hundreds died and many communities were burned to the ground. The flames had reached such intensity that people as far away as Iowa thought the fire was nearby. It was a story told around the world. In the dozen stories about The Great Hinckley fire written by The New York Times, not a single one mentioned John Blair.

John Blair was recognized for his heroism a few weeks following the firestorm - first by the African-American community with a gold badge and later by the Railroad authorities. He is the subject of a children's book by Josephine Nobisso, and his story holds a prominent place in Daniel Brown's Under a Flaming Sky. Blair died at age 68 in 1922 and is buried in Saint Paul’s Oakland Cemetery, very near his one-time home.

Born to an African fur trader and an Ojibwe woman, George Bonga and his siblings are considered to be the first people of African descent born in the territory that would later become the state of Minnesota. Bonga played many roles during his lifetime, including voyageur, entrepreneur and diplomat - but most importantly he is one of Minnesota's true Black pioneers. Get to know his story.

Taken 100 years apart, a video that captured ex-police officer killing George Floyd bears an eery resemblance to a photograph of three Black men who were lynched in Duluth in 1920. Twin Cities PBS Senior Producer Daniel Bergin reflects on what the images – one moving, one still, both disturbing – say about Minnesota’s long history of systemic racism.