How Does Minnesota Compare to the Nation in Racial Equity?

In some measures, the “Star of the North” is failing communities of color.

Rates of inequity in Minnesota fall below national standards and show how historical divides have created ongoing consequences for people with darker skin. Some disparities are driven by historical and racist practices like redlining. Others are escalated by the wealth and success of white residents. Below are some key metrics of racial disparities in Minnesota. Data is sourced from organizations that include the U.S. Census, Minnesota Compass and the Wilder Research Foundation.

Poverty

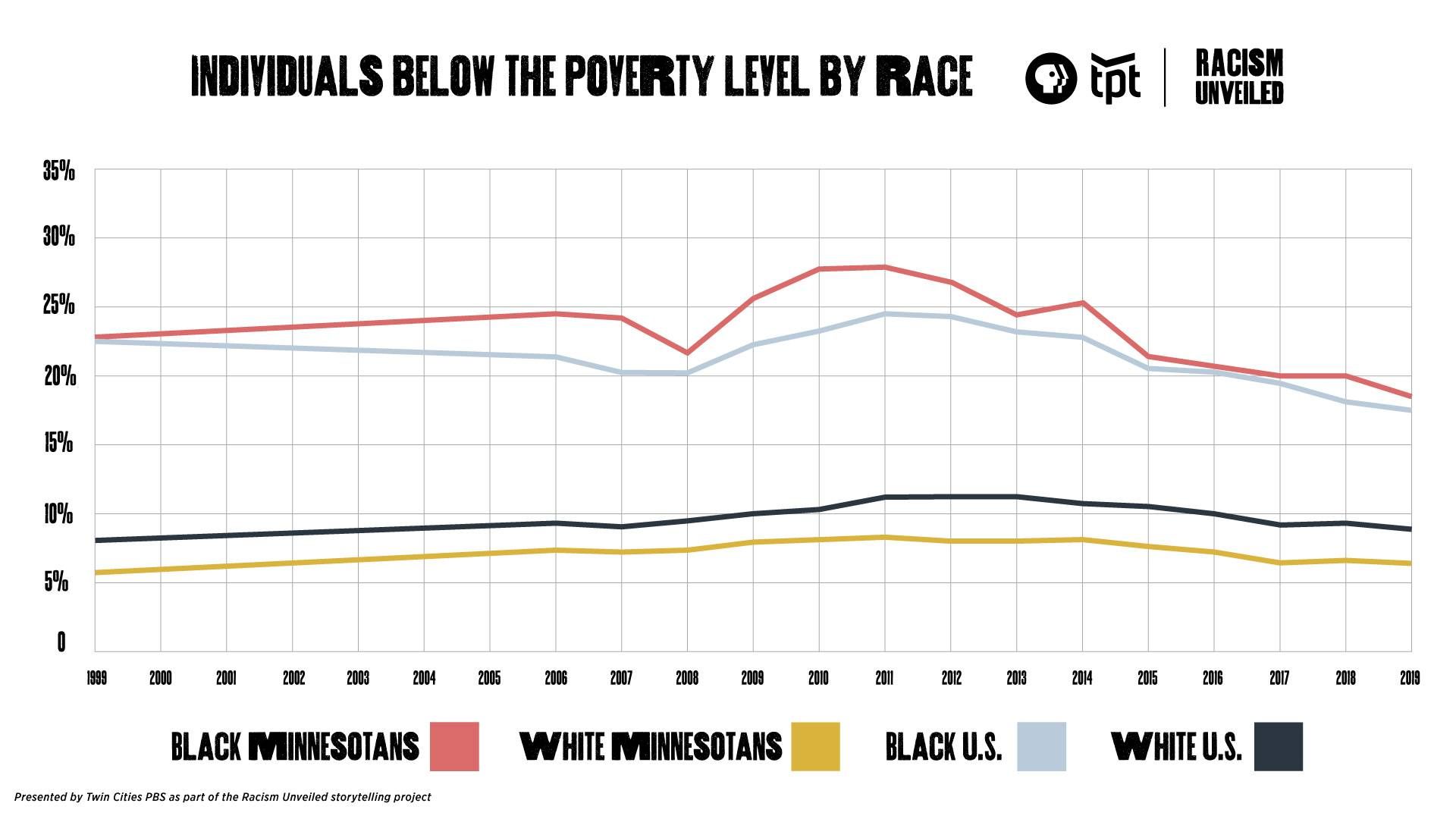

Poverty is a major predictor for life challenges and obstacles. Those with less income often have unstable housing, fewer educational opportunities and more unchecked health issues. More often in Minnesota, those in poverty have been people of color.

In the past two decades, a higher share of Minnesotans of color have lived in poverty than the rest of the nation - but poverty rates among white people have consistently outperformed national standards. And the inequality gap between Black and white families’ annual income ranks among the worst in the nation. With less money earned, a greater percentage is spent on housing.

Homeownership

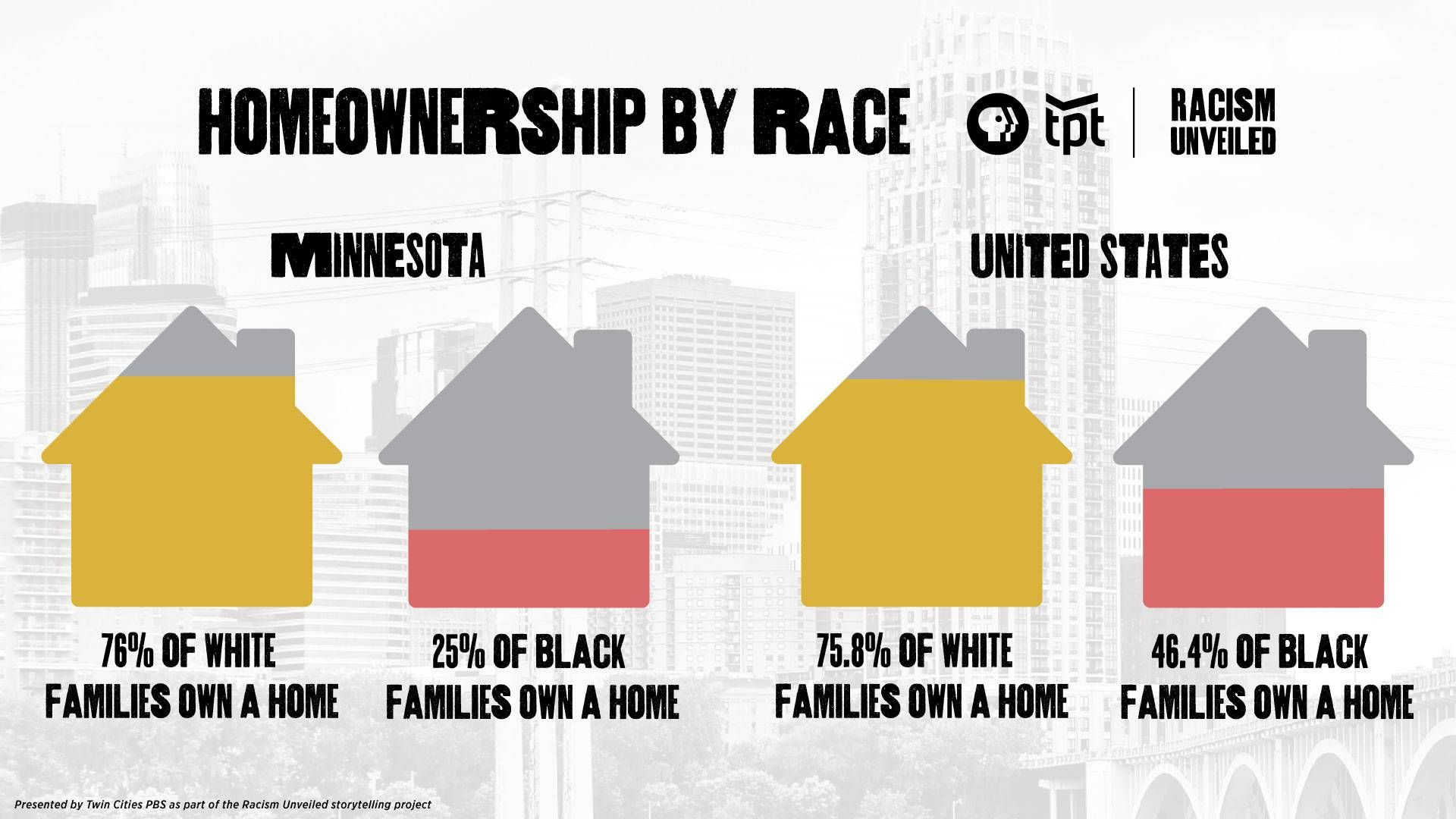

Around 76% of white residents in Minnesota own a home, creating opportunities to pass generational wealth and assets to other family members. Less than one out of every four Black people here can say the same, creating a disparity that the Department of Housing says is one of largest in the nation.

For those who do own a home, more people of color pay a third of their income on housing than white residents. Making matters worse, financial crises like the one spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic put residents at a heightened risk of becoming homeless - a population that is overrepresented by Black and Native American people. Living on the streets increases the risk for health issues that follow some people for the rest of their lives. But health inequity has long been an issue in Minnesota.

Health Equity

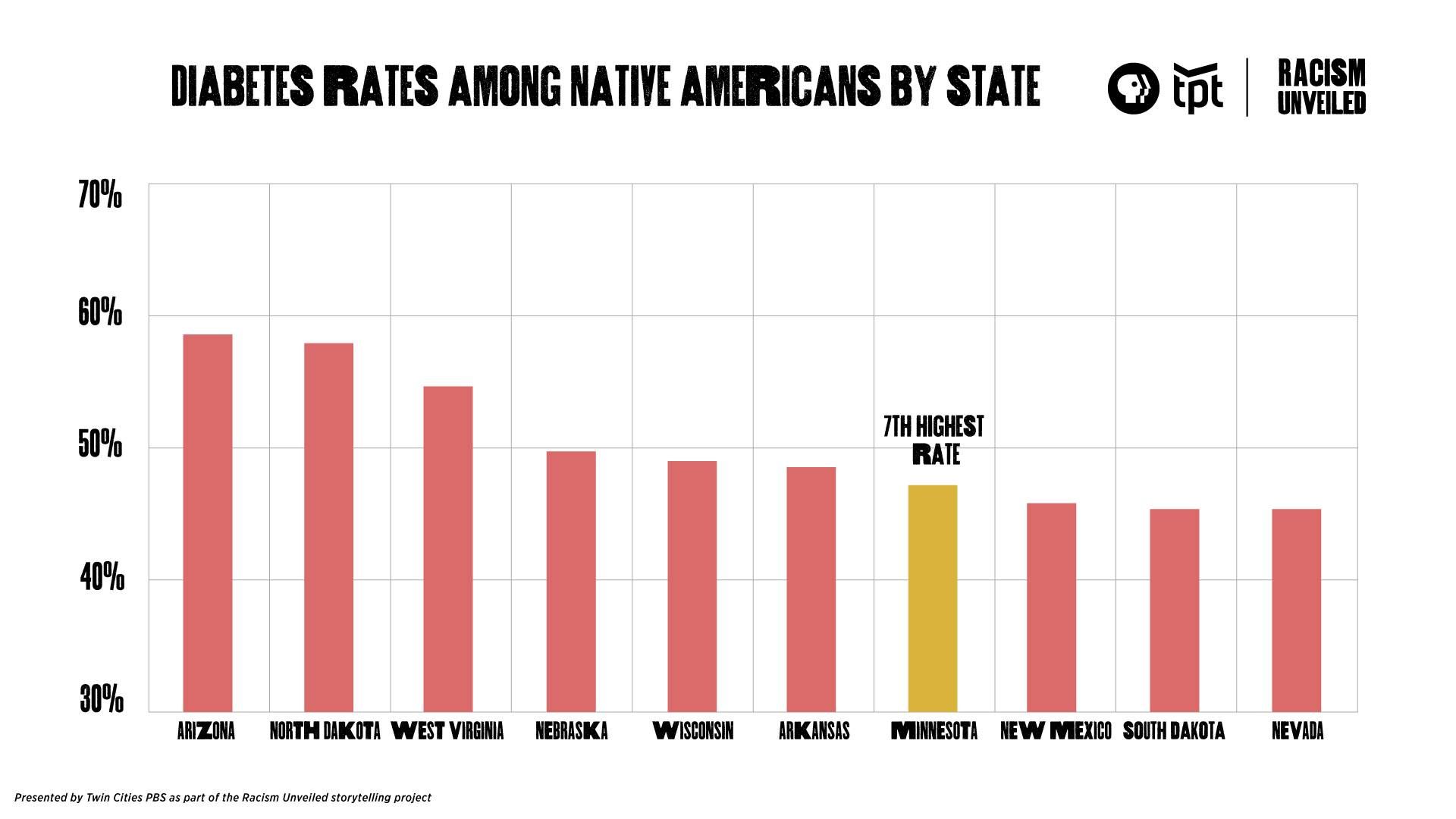

Minnesotans are healthier than the nation in many measures, but that changes by race. A larger share of Black residents than white reported being in poor or fair health. Those disparities persist in the data, which shows that nearly half of all Native American people here have been diagnosed with diabetes. That ranks Minnesota as the seventh worst state for diabetes among Native Americans in the country, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Health coverage could fight against these health disparities, but few people of color have such insurance here. Even fewer people of color own businesses.

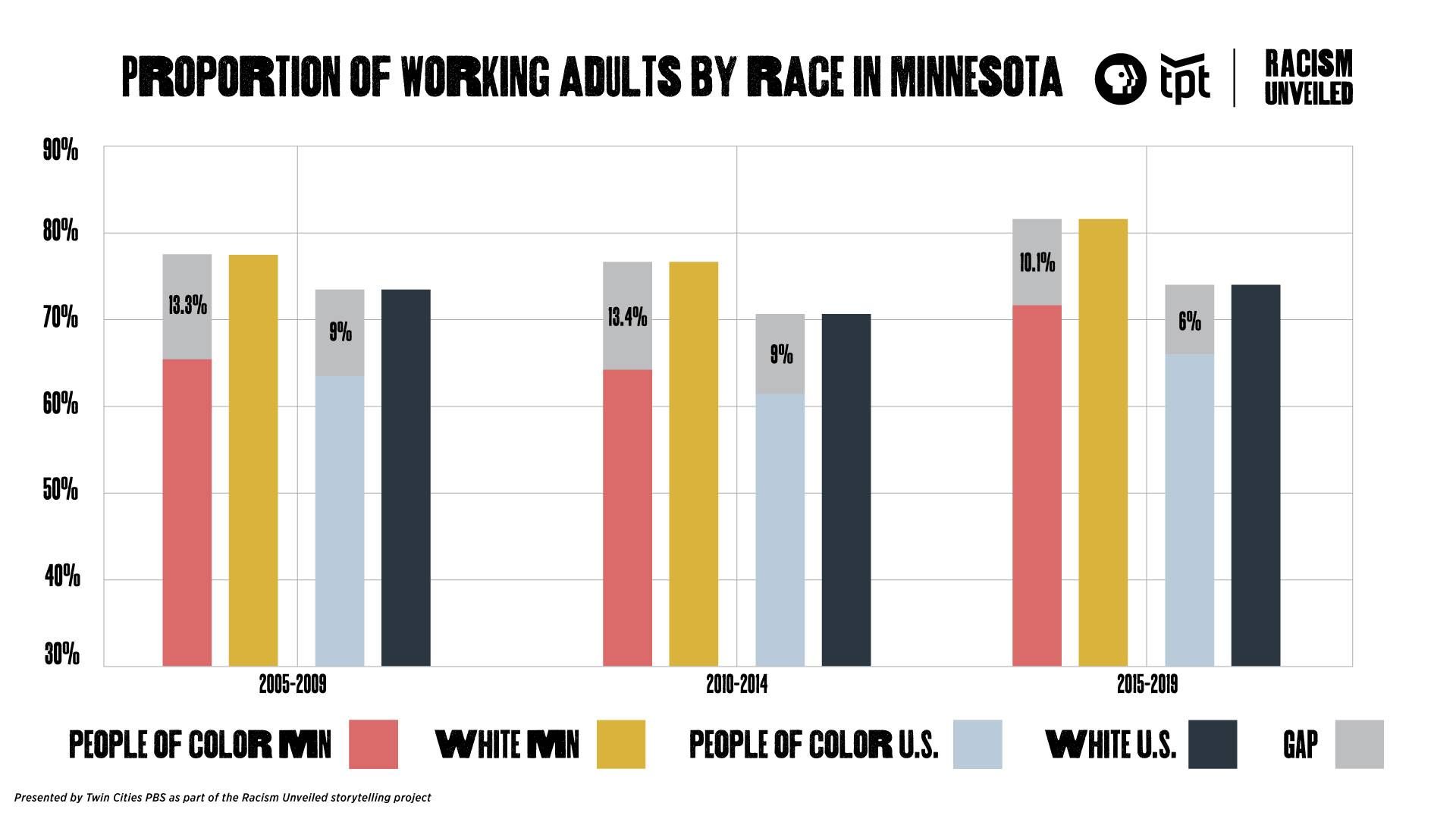

Jobs

Minnesota employs huge numbers of people, ranking second in the nation for the share of adults working in the state. Yet the employment gap between white residents and people of color is one of the worst in the nation, and the number of minority-owned businesses in Minnesota is three times below the national average.

With fewer employment opportunities, there are fewer chances to get employer-provided health insurance. Education could pave the way towards better job opportunities, but that field is also troubled by disparities.

Education / Punishment

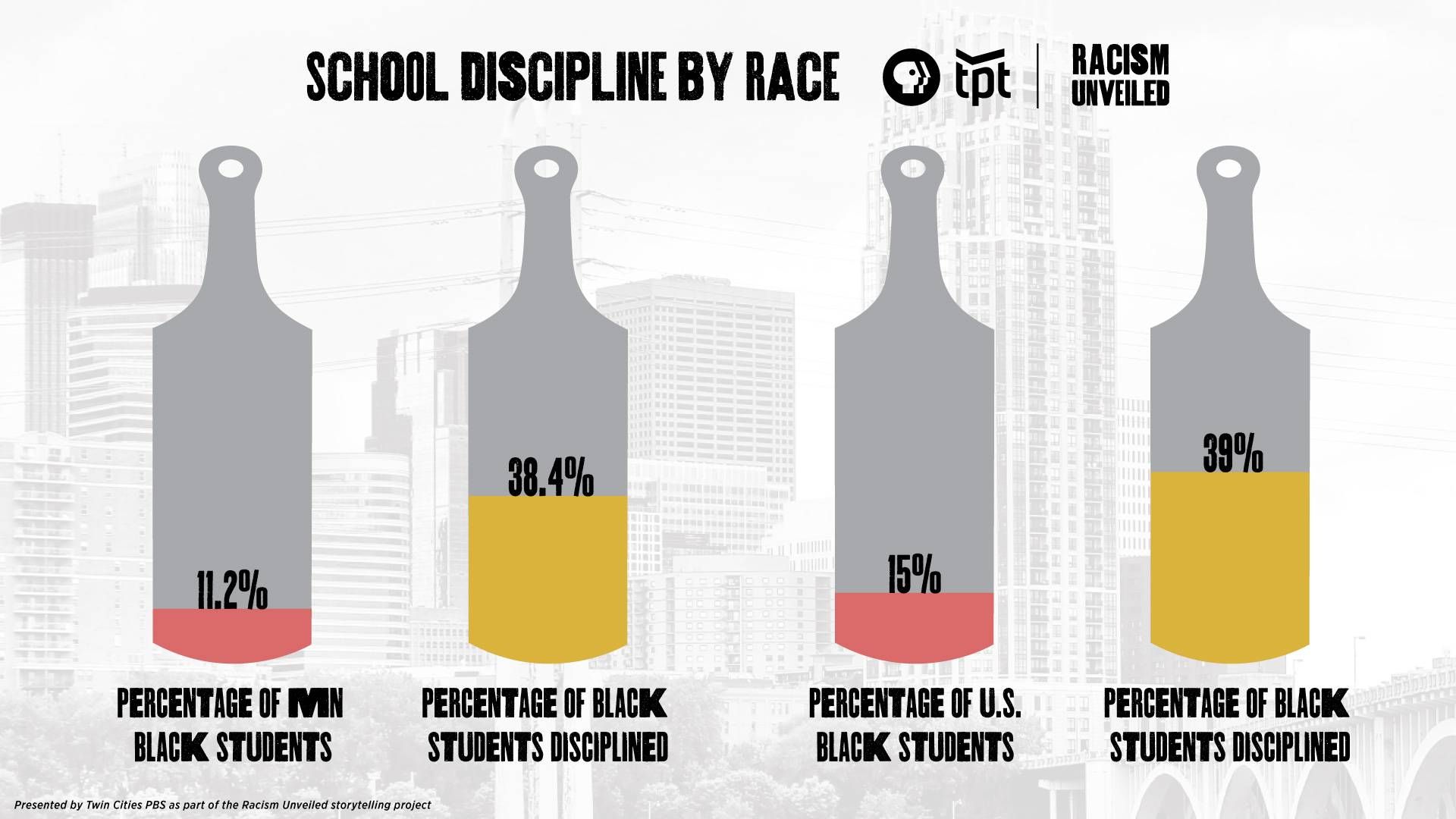

College graduation rates in the “Star of the North” beat the nation, and a higher percentage of residents have earned a Bachelor’s degree. But just one out of every five of those residents with a Bachelor’s are Black - falling below the national average. And even though Black students represent a tenth of the Minnesota school population, they comprise 38% of all students who were suspended, excluded or expelled. That gap is just above the national average.

Such punishments can derail students’ success, putting them at higher risk of being caught in the justice system. These and other disparities riddling systems within Minnesota and America put people of color at a disadvantage.

Whether it’s housing, health, or jobs, Minnesota excels at achieving in a slew of areas without its minority residents.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

Along with other urban centers across the country, the Twin Cities have a history of racially discriminatory housing covenants that prevented people of color from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. That history ripples in the present-day affordable housing crisis: By limiting opportunities for home ownership, people of color were stripped of one key way to build equity over time. Discover more in “Mapping the Roots of Housing Disparities in Minneapolis.”

Data Reporter Kyeland Jackson left Louisville, Ky., Minnesota shortly after George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police. In "Tethered: How Race and Policing Binds Minneapolis to Louisville," he hones in on the racism-fueled policing disparities that led to both Floyd's and Breonna Taylor's deaths.

Saint Paul’s neighborhoods of color have a disproportionate number of vacant buildings than areas primarily occupied by white residents. That fact has a direct impact on crime rates, public-health risks and quality of life. Data reporter Kyeland Jackson examines the links between vacant properties and the city’s racial disparities.