How a Walker Art Center Program Helps People with Dementia Enjoy Art & Life

For most of Marv Lofquist’s life, taking a tour of an outdoor sculpture park would have been an out-of-the-ordinary activity. But when the retired chemistry professor was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease seven years ago, he began to appreciate art in a new way.

"If I got upset every time I didn’t remember something, I would be upset all day," says Lofquist. "I can't remember what I said five minutes ago, but I think then you turn around and say, 'Just enjoy what is there, right now.' I can look at things and appreciate them in ways I never thought I would."

Lofquist has joined a group of more than 1,000 people who have participated in Contemporary Journeys, a program at the Walker Art Center that is designed for people with dementia and Alzheimer’s, along with a partner, often a family member or friend.

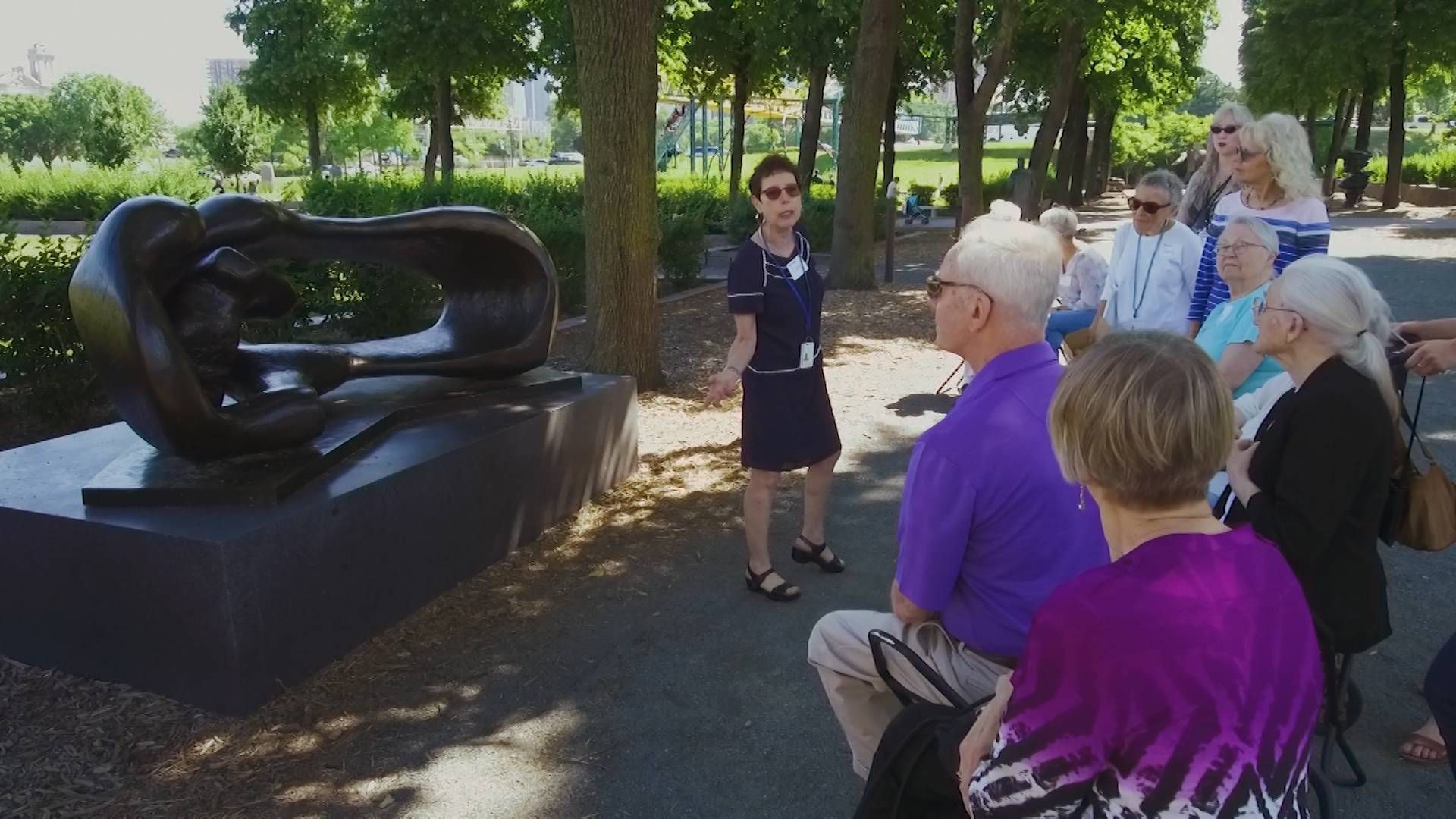

Ilene Krug Mojsilov helped found the program in 2009 and leads the tours once a month. Mojsilov says that people with dementia are uniquely open and without inhibition when interpreting what they see. "One thing I learned from this group is there's always someone that contributes something fresh and new that I haven't considered before. This group is totally in the moment and it makes me more sensitive to the world at large."

Tour guides make adjustments for the needs of the participants. They discuss only the artwork that is right in front of them and keep conversation focused on the present moment.

But does art therapy work? In an effort to better evaluate the effectiveness of the program, the Walker engaged Dr. Joseph Gaugler, a professor of long-term care and aging at the University of Minnesota's School of Public Health. Assessing the impact of art therapy is not as easy as determining whether or not a drug is effectively working, he says. "You're talking about outcomes of quality of life, wellbeing, kind of more humanistic outcomes that sometimes you can't always measure with a scale. Art therapy approaches can really help enhance the personhood of the person living with dementia. People with memory loss can still continue to express thoughts, feelings and emotions in a healthy way."

In addition to offering tours of the museum's collections, the program engages participants in making their own art that is inspired by artwork they’ve seen on the tour. "The art making, I think, amplifies the experience. It's a way to activate cognition and it's what jazzes me, too," Mojsilov says. "I'm looking for meaning in life. And I think care partners and our participants are looking for meaning, too."

Art making can decrease the stress, agitation and isolation often associated with memory loss. Elaine Lofquist is Marv’s wife and care partner. They met in high school and have been married for 53 years. "Doing something with just Marv and I, just alone, is fun, and we enjoy doing that," she says. "But having an activity that we can go to with other people is even more beneficial for us in terms of not feeling isolated."

Marv Lofquist agrees. "I think self isolation as one of the worst things you can do in any situation. But especially with memory loss, I don't want to be sitting there, not feeling like I can participate, cannot contribute. Getting a group like we had together to look at some art work or talk about some things… That’s what I still want to keep doing.... You know, what can I find enjoyable? But what can I find to do? What can I find that's meaningful?"

This search for a life with meaning and dignity may become more crucial as the number of people with Alzheimer's is expected to double in the next 30 years. According to Dr. Gaugler, "As more people unfortunately get Alzheimer’s Disease, you're going to start, I think, seeing the seeds of really an advocacy movement of people with memory loss stating that, 'I'm still here and my values, my opinions, my thoughts, preferences matter.'"

Marv Lofquist agrees that society could benefit from a shift in how it grapples with Alzheimer's Disease. "How can we turn some of the negativity around Alzheimer's and say, 'Let's just get on with it and accept it and deal with it and enjoy what we can?'"

Human beings are wired to crave social interaction, beauty and creativity - and the participants in the Walker's Contemporary Journeys program, who strive to live with meaning and dignity as they enjoy one day at a time, are no different.

Special Thanks: Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board, Rakhma Homes

Production Team: Kate McDonald, Brennan Vance, Carrie Clark, Terry Gray, Joe Demko, Ashleigh Rowe.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

In addition to helping those living with Alzheimer's Disease, art therapy can also have a tremendous impact on those who are on the Autism spectrum. Diagnosed with autism at the age of two, Minnesota artist Devin Wildes found his voice when he picked up a paint brush. Discover how art helped him find happiness, focus and belonging.

While Alzheimer's can be an isolating disease, singing in groups has been shown to improve memory, and to reduce anxiety and depression for both the person with dementia and their care partner. This is why Giving Voice Chorus started in 2014: To help serve people with memory loss and their caregivers through the power of singing. Find out how the organization has triggered a movement.