Hawona Sullivan Janzen Tells Untold Stories

Hawona Sullivan Janzen has been saved many times by art - and she believes that many people living in the midst of our painful present need that salvation. As an interdisciplinary artist and storyteller, she uses creative pursuits to channel the dreams and stories that have gone untold for too long. As we contend with a pandemic and continue to fight for racial justice, as we grieve for our society, Hawona is responding through storytelling in poetic, operatic and visual art - and she hopes that her work will save others.

When we think of what it means to demonstrate courage and to fight for a better reality for Black people in the U.S., we often envision the righteous protests that continue to fill our streets. But bravery exists in many different forms. In this interview series, we hear from Black women who are using performance art to speak up, undaunted in their fight against white supremacy and police violence.

In her own words, Hawona offers this reflection:

“In the way that I practice art, the idea is the art and the medium comes from what the idea tells me it needs in order to come into existence. I suppose nowadays I would fall into the school of ‘conceptual artist.’ I don’t know that I ever thought that before. I thought when I went through my poetry phase that I was a poet; and when I was in my puppetry phase that I was a puppeteer; and when I perform with the band, I’m a jazz singer; and when I’m on the stage, I’m an actress or a playwright. But I’ve since had time to reflect, to understand that the practice moves through the space in the way that it needs to for the idea to come into its own.

There was a time when [artistic forms] gave me great anxiety. I remember participating in a writing workshop in Bemidji with Joy Harjo. She is a poet, a musician and also a singer. [I asked her], ‘How do you reckon with people who can’t understand that you are all of those things?’ And then she turned to me and she said, ‘But I’m a storyteller.’ When she saw herself as a storyteller, then all of those things made sense, because then the story is the medium, and all of those other things are just a gift that chooses to push itself out front for that particular story. I have thought about that for years. It’s...very much about the whisper, the muse that tells me what the [medium] is.

I am always consumed by history. I’ve been spending a lot of time walking down by the Mississippi River. I was there one day and began to hear in my head a choir that was trying to deliver this story for me. I hit ‘record’ on my phone and just started singing the lines that I could remember. Later that night, I had this dream that I was in that spot, and that I could see this choir of Black and Brown skinned people all dressed in white, and they were on this bridge, and they were singing. There was this man that was at the edge of the water, and he had his back turned to me. And I kept saying, ‘Excuse me, excuse me,’ and he wouldn’t turn around. Finally he did, and I woke up. I didn’t know who he was, but he felt so familiar to me.

I had been curating this exhibit that was going downtown in the Hennepin Gallery - it was Minnesota Black History 101. I was going through the stuff, and there he was, the man in my dream - Rev. Robert Hickman. He was the founder of the Pilgrim Baptist Church, which was the first Black church in Minnesota. I read his story, which I wasn’t familiar with, and he and about 75 people came up the Mississippi River in a raft, so they were hugging the shore, escaping bondage, and started this church after they got here. I mentioned this to a friend, and he said, ‘There’s a brand-new book that I think you need to see.’ And he sent it to me and I read that Hickman made it up the river because a ferry boat called The Northerner allowed them to attach themselves to the boat, which pulled them up the river. But The Northerner was coming to Saint Paul to pick up the survivors of the Dakota War to take them into bondage. The very vessel that rescued these Black people, who were escaping from bondage, was coming to banish and take these Native people off of their own land.

Black stories and Native stories are constantly intertwined. I’m working on this choral opera about [all of this], and hoping to assemble a group of singers who would perform it with me down at the river. That story needs to be known by everyone.

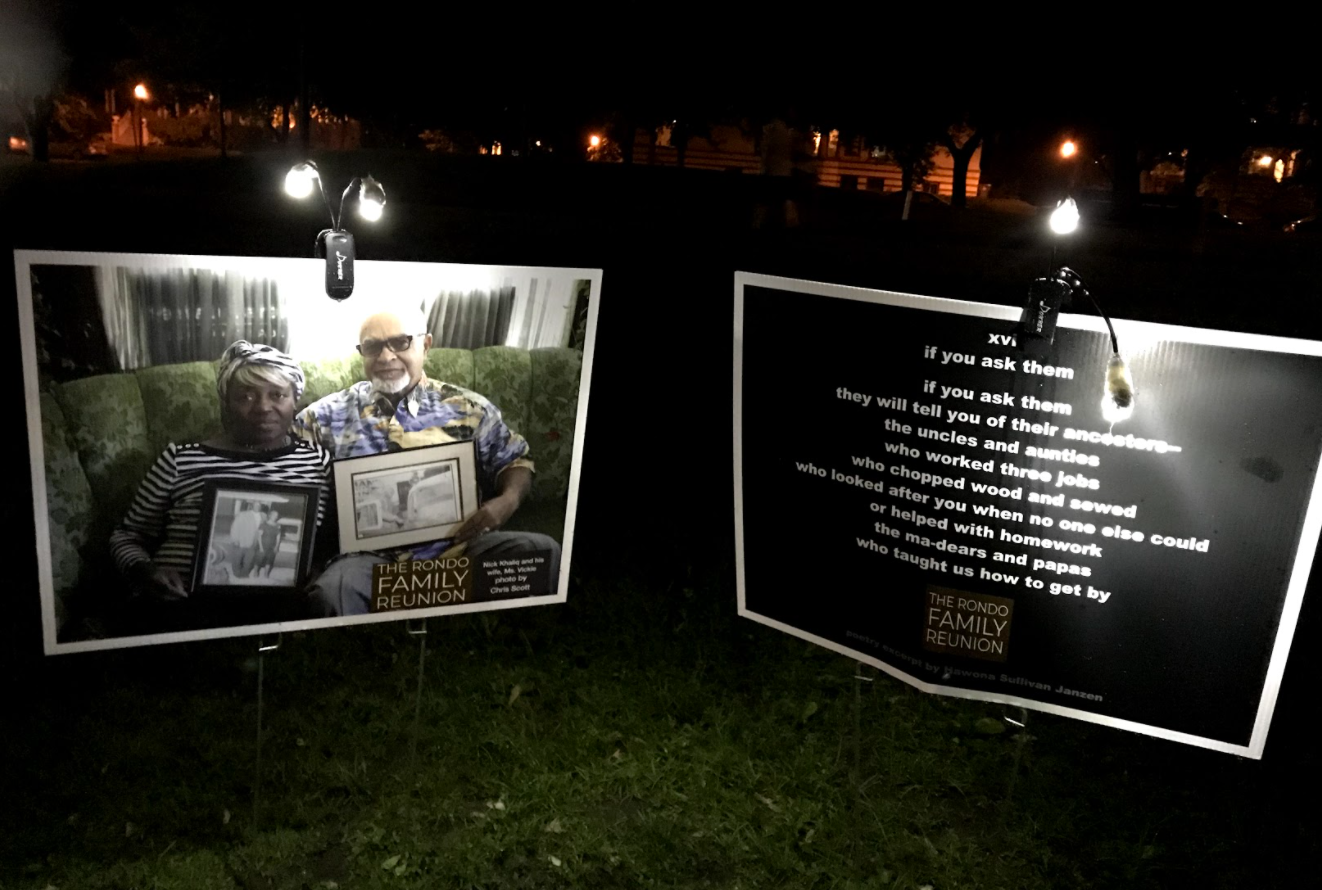

[About the Rondo Family Reunion Project:] I had been reading the transcripts and the papers that were created by the surveyors who came to the Twin Cities to scout for the right location for Interstate 94 to go over. And in that, they had written that Rondo was a ‘slum.’ And because they had chosen to write that Rondo was a ‘slum,’ it was easy for them to write that it was the recommended route, because by bringing this freeway through, it would be an ‘improvement.’ As I sat there reading that, I struggled with the Rondo that I have inhabited for much of my adult life, and I could not reckon what was in the papers with what I knew of Rondo. I made the decision to let those voices be heard [through poetry]. Those poems became lawn signs because they needed to inhabit the same physical space that the desecration had sought to inhabit. People needed to be able to walk through this promenade and know that there is beauty and wonder and extraordinary important truths in the people that inhabited that land. To preserve the real narratives is the way that you make people care. Black history is also history; Black places are also places. When you’re trying to figure out how America got somewhere, and you leave our story out, you’re not going to understand that.

The Rondo project was happening at the same time as another project - the Dale Street Bridge. I am one of three artists who were hired to design the Dale Street Bridge [the other two artists are Mica Anders and G.E. Patterson]. We spent six months talking to people in the community, asking what they want to see on this bridge. People kept saying, 'We want people to know that we’re here,' and 'We want people to know the story.' As you walk across that bridge, on the pillars on each side, is a casting of a house. We’re literally putting the houses back on Dale Street that were torn away. They have ledges where you might be able to put a stone, or a trinket, or a note. For those that are still grappling with the memories of what that place used to be, they can come and lay their burden down onto that bridge. In addition to that, I created a poem that came into existence from all the words that people had shared with us over the many events that we participated in. That poem will be etched into the sidewalk. It is written in such a way that the poem is read both forward and backwards, so it requires you to make the journey north and south, mirroring the journey of so many Black people, who came up from the South to live in Rondo. The poem is about who those inhabitants were from the earliest known time, all the way up to who will live there long after we are gone.

This whole bridge is a response to the question, What does it mean to destroy, remember, reckon? Every time someone drives under or walks across that bridge now, I’m hoping that there will be a little moment of salvation for them and for us, that we are honoring that story.

How do we prevent the destruction of Black places and spaces? Multiple mediums. We protest, we write letters, we buy property and work as a community to determine what goes on to that land. If we have already lost the land, we combat the violation and desecration of the memory. We reclaim ownership of the stories.

I think part of [my] hunger for the just-right medium comes from a childhood of women who were dreamers, who would sit and say, even if it was something as simple as making a dress, ‘What’s the right fabric for this dress to come into existence?’ Early on, I would dream of this thing before we went to the fabric store, and often go to the fabric store but not quite find the [right fabric]. My mother would roll her eyes, and we would have to go to another fabric store because she wanted the thing to be just so, and I wanted the thing to be just so. I remember saying to her at the second or third store, ‘I’m sorry I’m being so worrisome.’ And I remember her taking my face with her hand and saying, ‘You are right to be particular. Nobody ever completely missed anything because they were holding out for the thing that was what they wanted.’

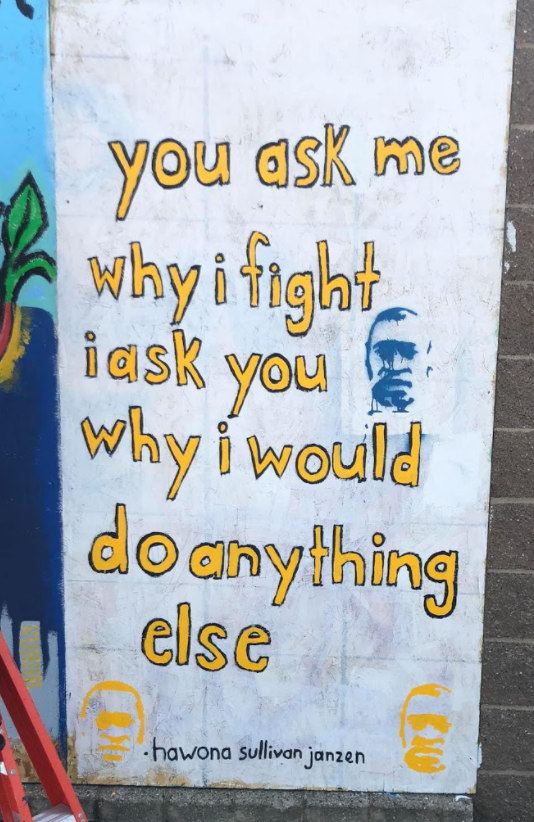

In the case of the projects with Springboard, a muralist wanted my words to paint on the side of a building that had been caught on fire. I was like, ‘I don’t yet have words for that.’ I had been making these little notes in my phone in the days after George Floyd’s death. He died on my daughter’s birthday. I’m no stranger to grief, having lost my youngest child a few years ago; I’m now also more accustomed to what it means to try to create something new after that, even in the midst of the grief. I needed to write something, just a couple of words, every day. When Springboard called me and asked if I would write some poems, they told me about a project that Seitu Jones was working on called ‘Blues 4 George.’ He had created this stencil of George Floyd’s face that was multiple layers, so you could decide how much detail you wanted, and he made it available for free online for people to download. And as soon as they said, ‘Blues 4 George,’ I looked back in my notes and realized that those little nuggets fell very nicely into four distinctive grief sessions, both for him and for his child, but also for us as a people. So then I wrote my 4 Blues 4 George.

I firmly believe that art is the only thing that can save us from ourselves. In order to say that, you have to believe a couple things. One of those is that we’re not quite right now, that we need to be saved - and I believe that is a perpetual stage of human existence. But one also has to believe that we can be saved. Someone used the phrase ‘artivist,’ and that feels right to me. I believe that I create out of compulsion, because I need to process, because I don’t want to grieve alone, and I don’t want other people to feel alone. I see my art as a necessary response to living in the world that we live in. I have been saved more times than I care to remember by art, both by my own and by art that was created by other people. Often times when I am in a concert hall, I look around at the faces of the people there, [and] I see them being saved over and over again. And so I’m constantly wondering who or what will be my next savior, what will I create that will be salvation for someone else? It used to feel like such a heavy thing, but now I just create and trust that the place it goes in the world is the place it needs to be. ”

"What really pulled me into being a performer and a creative was doing circus arts… this creative space that was so whimsical and magical and transformative. Bringing my Black body and my curvy body into that space really unlocked so much for me around futurism, and getting to be in different dimensions as a literal, physical, embodied person. Even in circus I was thinking of lynching, of histories." Get to know Junauda Petrus-Nasah in her own words.

Vanessa B. Agnes could not stand idly by as the city of Minneapolis grieved George Floyd’s police killing. So, in a 10-day period of time, she curated “the Uprising Vol. I.” This June 2020 event brought immense healing to the hundreds of Twin Cities residents, who gathered in a church parking lot to experience stories, spoken word poetry, dance, and song. Now, her new performing arts collective, Dark Muse Performing Arts, is flourishing and spreading hope throughout the Twin Cities.

Deneane Richburg founded the modern dance-figure skating-social justice collective Brownbody to create mesmerizing works in which the past cuts right through to the present like a sharp pair of scissors. Find out how she blends artistic genres with African diasporic history in this story from Minnesota Original.