Get to Know the Gilded-Age Visionaries Who Dreamed Up Minneapolis' Parks

Twin Cities parks have long ranked among the top in the nation in access, acreage, amenities and the cities' investment in expansive green space. In Minneapolis, alone, 15% of the city's area is reserved for parks, and 97% of urban residents are within a 10-minute walk from public recreation areas.

But this top-in-the-nation badge of honor didn't happen by accident. A group of forward-thinking visionaries with strong relationships (and deep pockets) worked together to ensure that Minneapolis residents had plenty of green space to experience enjoyment and entertainment for years to come. So without further adieu, we introduce you to four of them:

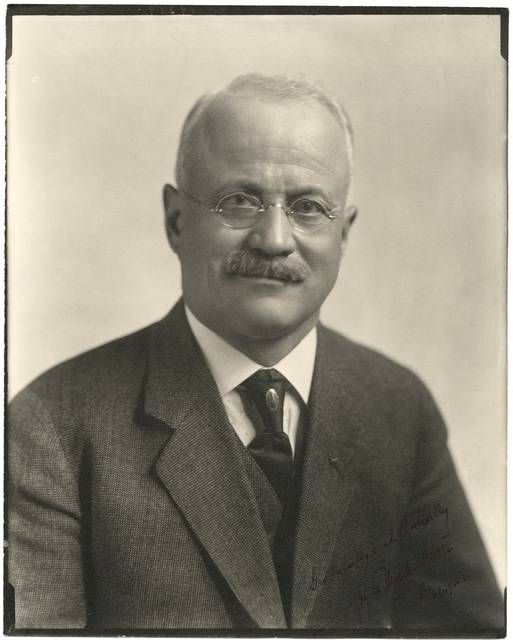

Theodore Wirth

Theodore Wirth is a household name for many Minneapolitans. The Superintendent of Parks from 1906 to 1935, Wirth was widely recognized as the dean of the park movement in America. During his tenure, the park system tripled in acreage - taking up 14 percent of the city. He oversaw the creation of the first playgrounds in Minneapolis parks, reshaped the city’s lakeshores and built its parkways.

Born in Switzerland in 1863, Wirth came to the U.S. at age 25. Prior to moving to Minneapolis, he gained notoriety as the creator of the first public rose garden in the U.S. (located in Hartford, Conn).

Wirth came to Minneapolis just as the city was emerging from the grip of the Great Depression and residents were looking for more public recreational facilities in the parks. With a goal of having a playground within a quarter-mile of every child in the city, one of Wirth's first projects revolved around creating the city's first playgrounds. Years of neglect during the Depression left the city's now-famous lakes "unsightly and unsanitary." Wirth oversaw the dredging and filling of the lakes, redefining the shorelines of nearly all of them and connecting some of lakes with channels. Another of Wirth's notable contributions is the Grand Rounds. Wirth managed their initial construction and improvement, and introduced the plan for Victory Memorial Drive. The Park Board's five golf courses were also created during Wirth's tenure.

Behind the scenes, Wirth created the first professional organization to manage the parks, hiring full-time bookkeepers, engineers, horticulturists, recreation directors and more.

Forced into retirement in 1935 due to civil service age rules, Wirth remained involved as Superintendent Emeritus and continued to live in the superintendent's house until 1945. Three years after his retirement, Minneapolis's largest park was dubbed "Theodore Wirth Park."

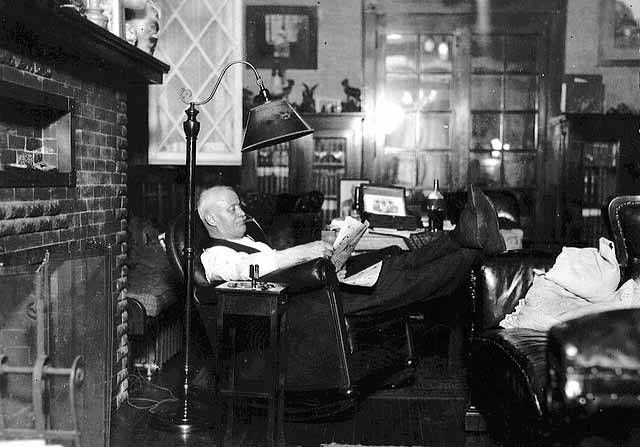

Charles Loring

There are some historical figures whose list of accomplishments make you wonder if they ever slept. Charles M. Loring is called the "Father of Minneapolis Parks" for his dedication to improving the city through dedicated public green space. In addition, he also owned three flour mills, co-founded the Soo Line Railroad, served in city government and presided over many associations that valued the natural environment.

Raised to be a sea captain, Charles Loring's life carried him in a different direction, and in 1860, he moved to Minneapolis at the age of 27. Perhaps because of his nautical roots, Loring had a keen eye for the intersection of nature, water and peoples' livelihoods. He sold supplies to lumber workers on the river, converted mills to run on hydropower, and co-founded the MN Electric Light and Electric Motive Power Company, which supplied power from the first hydroelectric central powerplant in the U.S. Not one to rest on any laurels, Loring was also a director of three insurance and loan companies; co-founded the Minnesota Homeopathic Medical College; served as president of the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce, the Minnesota Forestry Association, the National Park and Outdoor Association and the Lakewood Cemetery Association; and organized the first Minnesota Flower Show (because, of course, he was a member of the MN Horticultural Society). And let's just say that this is a very abbreviated list of his professional associations.

As the first president of the newly created Minneapolis Park Board, Loring worked to implement and expand upon landscape architect Horace Cleveland's vision of interconnected public green spaces organized around the city's lakes, creeks and river. Through his business connections and donations, Loring was able to secure property for public use that we now know as the Chain of Lakes and Minnehaha Creek Park areas. He also was one of the first to advocate for children's play equipment in parks. He personally funded the development of park amenities, and an endowment to purchase and care for elm trees honoring WWI soldiers along Victory Memorial Parkway. In 1916, Arbor Day was renamed Charles Loring Day in Minneapolis, and school children planted more than 1,000 elms in his honor.

Charles Loring is buried in Lakewood Cemetery - which he helped to create. His monument reads "Father of Parks."

Eloise Butler

The namesake of the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary was a reluctant teacher whose approach to hands-on science and preserving the natural landscape made her ahead of her time.

Born in Maine in 1851, Butler's fascination with plant identification began early under the tutelage of her aunt. Keenly intelligent, Butler followed the only viable path for scholarly women at the time: She became a teacher (although she did not enjoy it). Butler moved to Minneapolis at age 23 to take advantage of well-paid teaching positions offered in the growing city. In her 37-year career in education, she taught history and botany at Central and South High Schools. Although she disliked teaching, she was a pioneer in using gardening as a means to teach science. A 1906 South High yearbook warned against taking classes with Butler "unless you enjoy 10-mile walks through bog and swamp."

Butler broke with the conventions of her time in a slew of different ways. She was passionate about connecting young people with nature; demonstrated the importance of farm-to-table food; advocated for greenhouses connected to schools; discovered three species of algae (including Cosmarium Eloiseanum, which is named after her); wrote a regular column on city gardening for the Minneapolis Tribune; and campaigned for natural wild gardens in the city.

It was in this spirit that the Minneapolis Wild Botanic Garden was founded in 1907 - the first wildflower garden in the nation. In direct contrast to the cultivated and pruned gardens popular at the time, Butler's mission was to maintain an area as close to its natural state as possible. Beginning with three acres and two specimens that Butler grew in a pitcher over the winter, the garden grew through contributions from friends and neighbors. Today, the garden contains less biodiversity than it did in Butler's time, but with more than 500 plant species and 130 bird species, it's still quite impressive.

After her retirement from teaching in 1911, Butler was hired as the first curator of the native plant reserve (with a salary less than what most groundskeepers made). In part because she "lacked professional credentials," Butler struggled to find support and funding for the things she needed to maintain the gardens, relying instead on the support of fellow botanists and paying for things out of her own pocket.

In 1929, the Minneapolis Park Board named the garden in Butler’s honor. Four years later, she died on her way to tend the garden. Her ashes were spread among her wildflowers.

Maude Armatage

A visionary and a trailblazer, Maude Armatage led the charge to bring together Minneapolis parks and schools.

Born in 1870, Maude Dunsmoor enjoyed playing "un-ladylike" games - anything deemed more raucous than croquet - at school throughout her youth. Perhaps that experience planted the seed that would one day grow into a legacy of providing opportunities in and connections between schools and parks.

Maude married Arthur Armatage at age 19. Community-minded from the start, Maude Armatage was the first leader of the Camp Fire Girls in Minneapolis and, over the course of her life, took part in many organizations, including the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the League of Women Voters.

Armatage was also actively engaged in the campaign for women's rights in the United States. Known as a suffragist, Armatage didn't stop when the right to vote was won. She ran for a seat on the Minneapolis Park Board during the first general election in which women had the right to vote.

Minnesota women played a major role in the national fight for suffrage. Explore a timeline that chronicles their contributions, leading finally to the passage of the 19th Amendment into law.

In June 1921, Armatage won the position of Commissioner at Large, simultaneously becoming one of the first Minnesota women to run for public office, the first woman elected to a Minneapolis municipal office and the first woman elected to the Park Board. She was the only woman on the Board for the full 30 years in which she served.

Armatage was tenacious in her pursuit of safe, accessible, fun public spaces for the community. According to a 1978 article in the Minneapolis Tribune, one long-time member of the Board said "I'd rather try to stop a speeding locomotive than Maude when she gets a steam up."

She was unanimously elected Vice President of the Minneapolis Park Board from 1924 to 1926. In this role, she traveled to Detroit to study how that city approached cooperation between the Department of Recreation and the Board of Education. In 1948, after the idea had been sidelined by the Great Depression and World War II, Armatage sponsored a joint resolution between the Minneapolis Park Board and School Board that led to the cooperative development of Waite, Kenny, Cleveland (and in 1952 Armatage) parks and schools.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

In the years between the world wars, Minneapolis residents gathered in the city's parks on balmy summer nights to raise their voices in song. Those "community sings" events eventually took on a competitive note as each community tried to out-sing those within a stone's throw. Discover how "participatory, public entertainment clearly held enough power and potency to draw thousands of people from their homes with the singular motivation of singing in unison."

Urban Lights Music record store owner, Tim Wilson, remembers the early days of the Twin Cities hip-hop scene, including an epic party that took place at McRae Park in the '80s. Find how hip-hop happened in Twin Cities parks.

Craving new routes for your daily walks? Both Minneapolis and Saint Paul feature “outdoor galleries” of vibrant murals that might just fulfill your hunger for beauty in these stay-at-home times. Your murals walking tours in Minneapolis and in Saint Paul await, complete with maps for easy navigation.