Fly Until You Die

A conversation with Hmong pilots in the Vietnam War

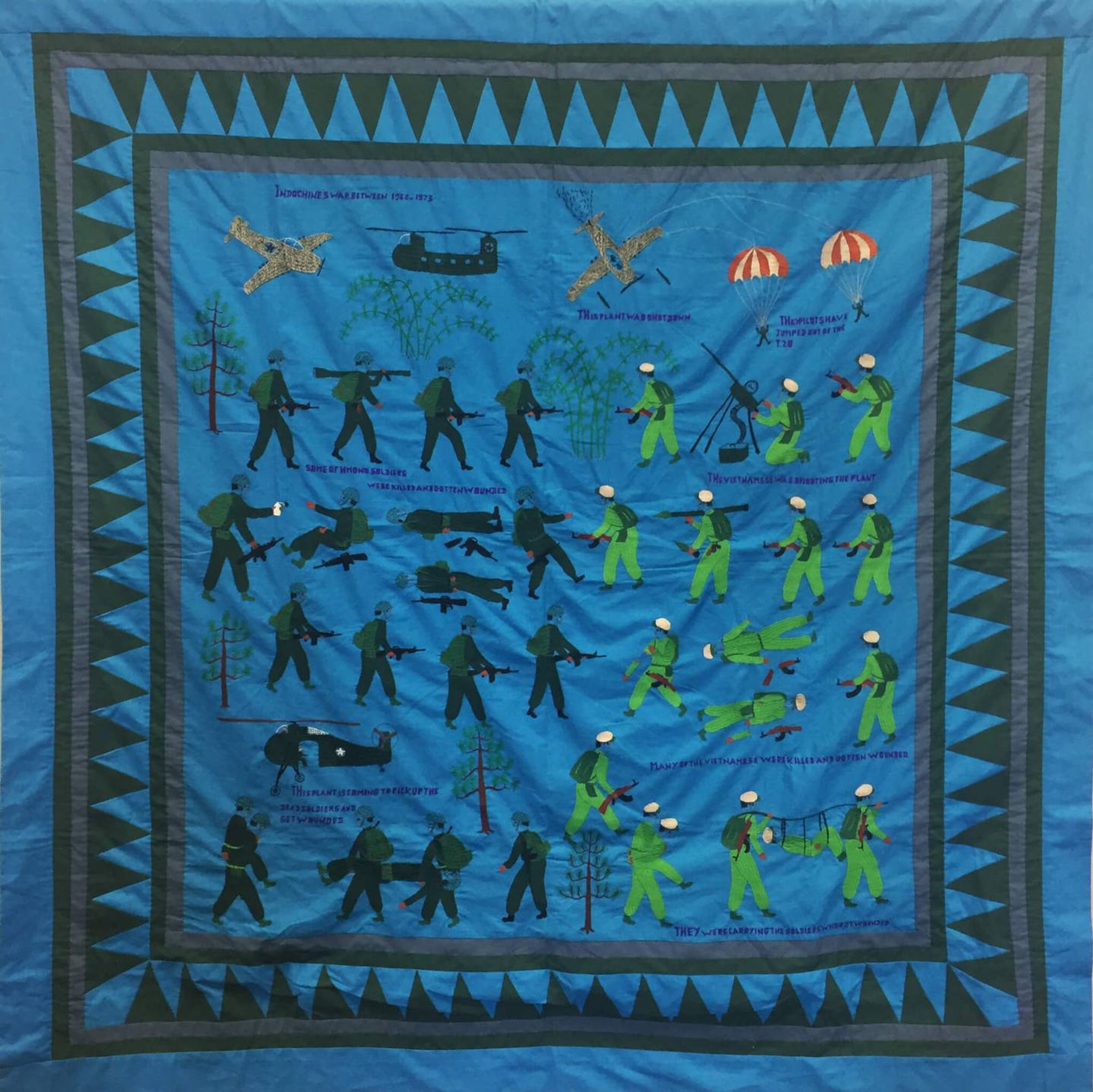

In the shadows of the Vietnam War, the CIA conducted a secret war in Laos that relied on Hmong soldiers to disrupt supply lines on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and prevent the threat of communism from spreading deeper into Southeast Asia. Tens of thousands died, both in the fight and in the escape.

During the war, a few dozen ethnic minority men from Laos were trained in Udorn, Thailand by the US Air Force and CIA to become pilots. Beginning in 1964, this clandestine operation known as Operation Waterpump, skirted Lao neutrality in order to bolster the Royal Lao Air Force and their own war efforts.

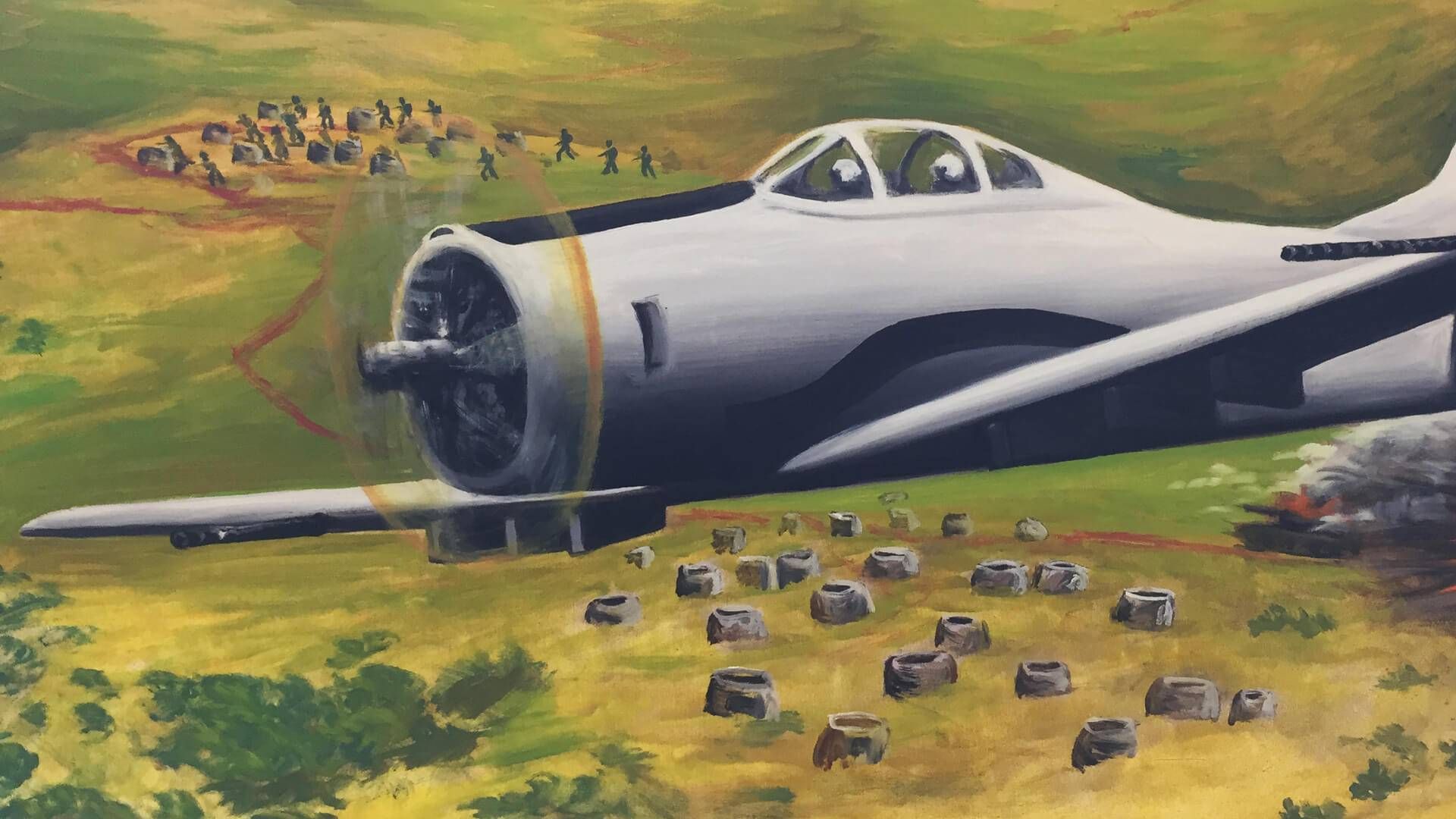

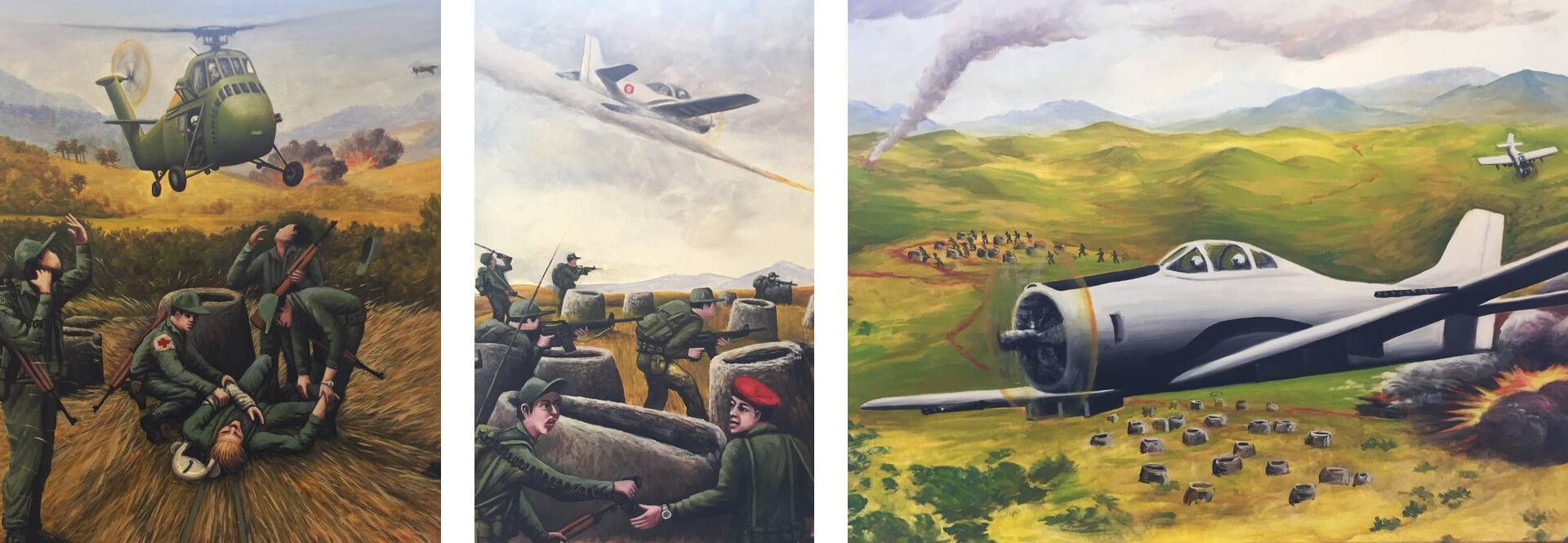

The small group of pilots flew T-28 military aircraft from Long Tieng against the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese positions. They were part of the regular Royal Lao Air Force, but took orders directly from General Vang Pao, a champion and hero of the Hmong people.

Their stories were a secret for 40 years. Until now.

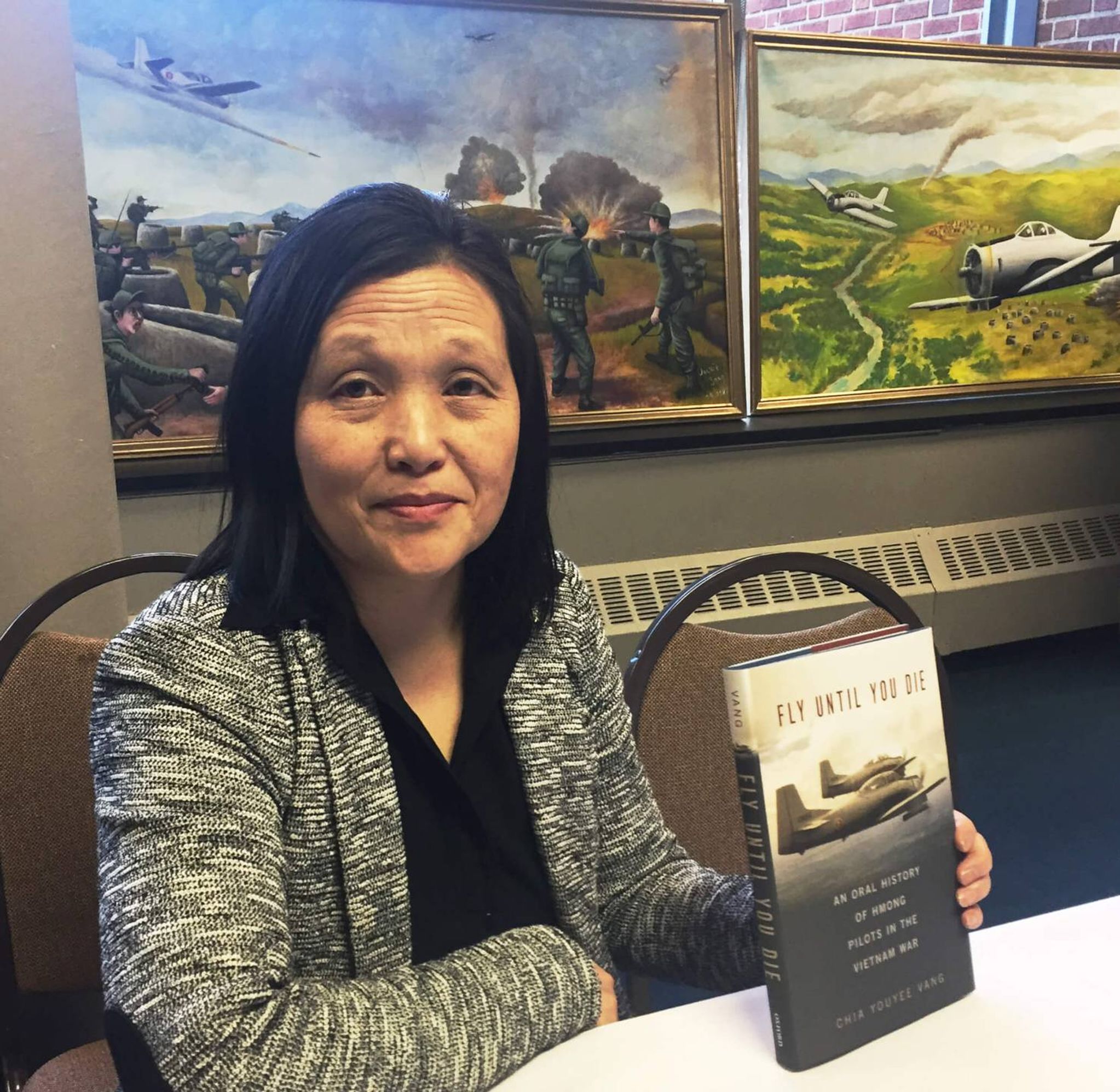

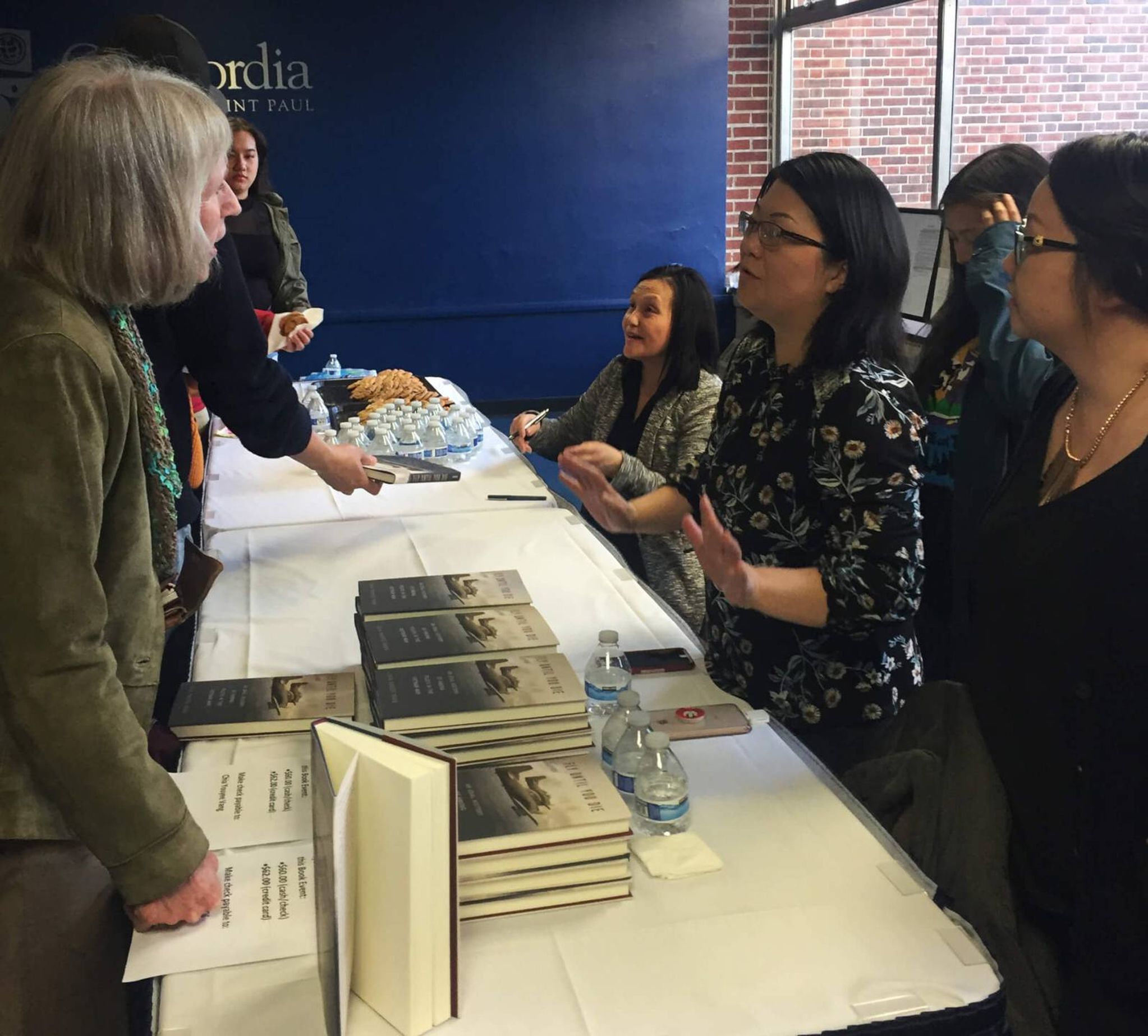

In 2012, a group of some of those Hmong pilots attended a reunion in the U.S. They realized that they were getting older and they didn’t want their stories to be forgotten and die with them. They decided to reach out to author and historian Dr. Chia Youyee Vang. The result? A new collection of their stories, 6 years in the making. Vang traveled the country and conducted hundreds of hours of research in order to capture and preserve their stories in her new book, "Fly Until You Die: An Oral History of Hmong Pilots in the Vietnam War." This book not only shares the stories of the Hmong T-28 pilots, but shares them in their own words.

On April 18th, 2019 at Concordia University in St. Paul, Vang was joined by some of the T-28 pilots, their children and military leaders for a Vietnam War Roundtable discussion. Hosted by Lee Pao Xiong, Director of the Center for Hmong Studies at Concordia University, the roundtable was enlightening and offered deeper perspective on this turbulent history.

Their stories, their words

Tou Fong Vang, eldest son of legendary pilot Vang Sue, shared, “These stories would be lost without her work. The stories were so secret that we need this [the book] to look into it and shine a light.”

Vang said, “It’s a gift that they have given to me, to tell their stories. This book is not my book. The stories are their stories. I just happened to be blessed with the pilots’ trust in me to tell their stories.”

"It’s about war, memory and healing as well."

Tong Vang, president of the Hmong SGU, shared, “This is the first time that we get to write our own history with the help of a Hmong author. For 40 years we haven’t shared these stories because the government prevented us from talking because it was a secret.”

The story is about the pilots, but is also about the widows, families, and parents left behind. For Chia Vang, it’s also personal. “It’s about war, memory and healing as well. This is emotional for me, too. I was a small child during that time, but I share in their [pilots’] migration story, their refugee story. We have that in common.”

Her hope is that in sharing these stories, she can help to shatter stereotype that Hmong were illiterate, uneducated, buffalo herders. “In fact, the pilots were the most elite of our time. They learned how to fly,” she said.

During the presentation, Vang played a video clip from her interview with Bill Lair, an influential Central Intelligence Agency paramilitary officer, before he passed away. He shared, “I could tell they [Hmong] were intelligent. It doesn’t have to do with education. You need intelligence before you can get educated and do big things.”

During the Vietnam War, 36 Hmong men earned their wings as T-28 fighter pilots. Several others became helicopter pilots and transport carrier pilots.

Tong Vang shared:

“Cherish and remember Hmong pilots because if it weren’t for them, many many more would have died.”

“People on the ground relied so much on the T-28 pilots and their support. When people heard the sound of a T-28, it gave them hope even though they knew that the enemy was close,” Vang said.

They flew hard, they fought hard

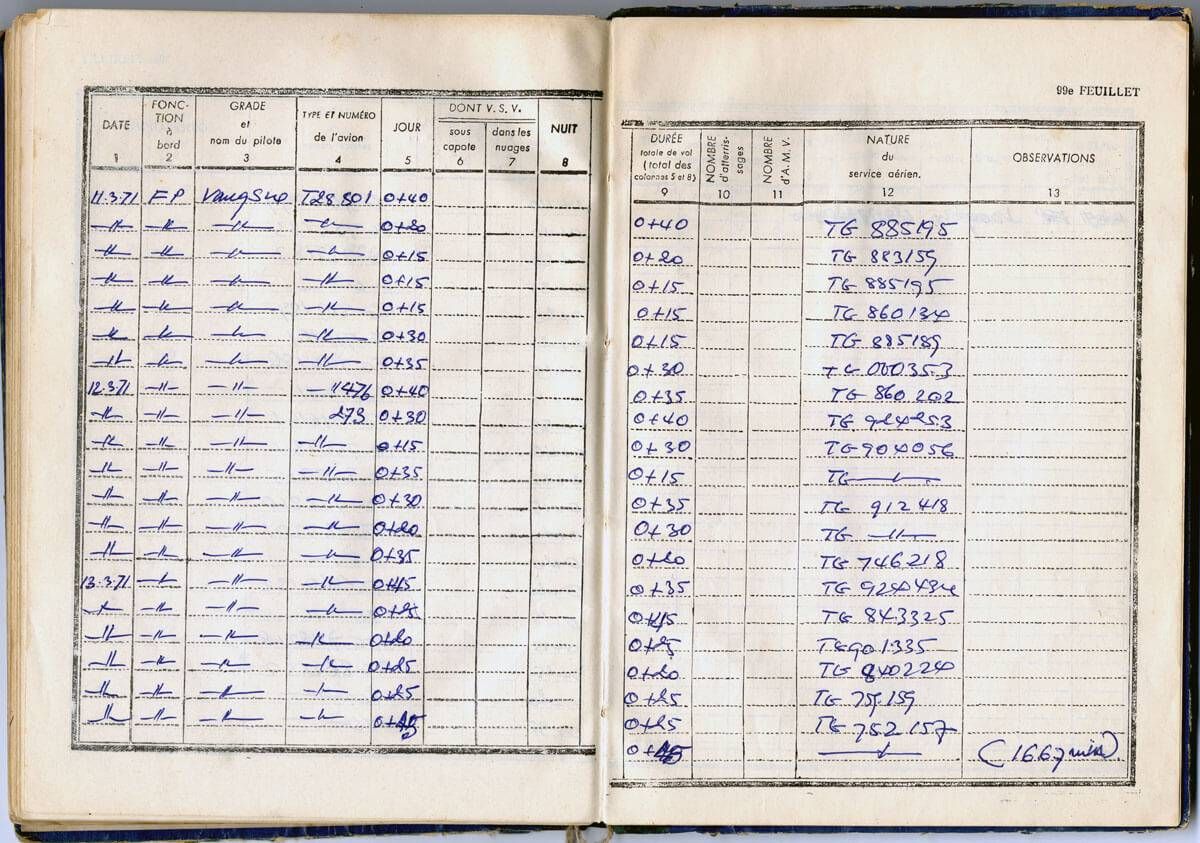

Toufong Vang discovered his father’s flight logs and was astonished at what he found. 1,600 missions were recorded in his flight log.

“He averaged 14-15 flights per day. Each time he was up there, he was exposed to gunfire. And he flew for 14 days straight, with 14 missions a day. He’d have a day break then do it again,” he said of his father’s service with emotion in his voice. “They flew hard, they fought hard. The Hmong T-28 pilots were the most experienced of their time. Their expertise was widely revered by veterans who knew them.”

Being a pilot was extremely dangerous, with a 50% casualty rate due to weather, equipment, lack of training, gunfire and rugged terrain. Because the pilots were key in supporting ground troops, they flew dangerously close to the ground. U.S. pilots said in a video interview clip, “We’d look down from where we were flying and they were flying T-28’s on the treetops!”

This extreme level of service, dedication and sacrifice inspired Vang to give the book its title. “For Hmong pilots, there was no exit strategy. They fly until they die or are injured. There is no plan to come home after serving a year. No R and R. The pilots who are here today are only here because they were injured.“

T-28 pilot Lee Ya shared, “I am proud of this book. It tells the ugly, bad, and good about we the Hmong pilots. This book, Fly Until You Die, means exactly what the title says.”

Pain and loss

The Secret War in Laos is oftentimes a story that is misunderstood and separated from the broader story of the Vietnam War. Vang hopes that these stories of the pilots can play a role in helping to reclaim the narrative and build deeper understanding about the crucial role of the Hmong in the war and the great sacrifices that were made on behalf of the U.S.

For Vang, the process of gathering these stories hasn’t always been easy. “For four decades, they [the pilots] were trying to forget. And now I am asking. The pain is there like it was yesterday.”

Lieutenant Colonel Tonfu Vang served as Genral Vang Pao’s Secretary during the war. He shared, “The loss and sacrifice was very heavy for pilots and families. I experienced this myself when my cousin crashed on a solo flight in the mountains above Long Tieng. The pilots deserve the name of this book.”

And for those on the ground? Between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. conducted 580,000 bombing missions, dropping more than two million tons of explosives on Laos making it the most heavily bombed country per capita in history. Vang said:

“I cannot believe that people survived that kind of bombing.”

Since the bombing ceased, over 20,000 people in Laos have been killed or maimed by unexploded ordnance (UXO).

Sharing now for future generations

Maj. Vang Seu was the last of the Hmong T-28 pilots to be killed in action. “This is the start of a conversation about ‘Who is this man?’,” said his son, Toufong Vang. "Hmong people will remember the contributions of the pilots. The pilots that were killed have a legacy.”

T-28 pilot Yang Phong shared, “The book is very important in telling our story and preserving it for younger generations. This book was very healing for me.”

Little recognition for heroes

Those pilots who did survive mostly sought refuge in the United States after the war.

Although Vang captured many of their stories she shared, “There are still a lot of unanswered questions. But this book will ignite conversation, and deeper appreciation for the sacrifice of the Hmong during the Vietnam War.” She hopes that it will validate their experiences and contributions, saying:

“We paid for our presence here in the U.S. with blood that was shed during the war.”

“35,000 Hmong died. We served this country [U.S.] for 15 years before we were allowed to come here. Many in the U.S. didn’t serve for that long,” said Tong Vang.

“I want recognition for our pilots,” said Toufong Vang. “For the last 40-plus years, I have been carrying the Distinguished Flying Cross that my father received. I met a veteran who remembered how that honor was given to him, and it was not official. This un-thoughtful treatment of the Hmong over the years is a big injustice.”

During a question and answer during the event, Dave Mandt, one of the founders of the Hmong American Veteran Alliance, shared, “I have always had so much respect for these guys. So many people don’t understand or appreciate the full story. I just want to say to you- Thank you for your service.”

“All of you that are here need to praise these two pilots. If it weren’t for them, many more would have died. They are great heroes,” Tong Vang said.

A wife of one of the pilots in the audience shared:

“This book is a cry from the grave. It’s a cry for formal recognition, and for dignity."

She concluded the evening by saying, "I can feel the pain today from the lack of recognition. This is our truth. Sharing these stories is a healing process that will help to close decades-long wounds.”

The Vietnam War Roundtable is partially funded by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota. This article is funded by the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation.

Learn more

The Vietnam War Roundtable is a partnership of TPT, the Minnesota Military Museum and Concordia University.

Share your own story at the Minnesota Remembers Vietnam Story Wall

Watch America’s Secret War online

Purchase Dr. Vang's book on Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/Fly-Until-You-Die-History/dp/0190622148