Explore the Schmidt Brewery, a Castle of Lagers and Legacies

Many of us learn about U.S. history through the lenses of war and politics, but there are so many other ways to understand the impact of local, national and global events. Art, for example. Or music.

But what about beer?

One Saint Paul brewery location, with multiple owners and more than 160 years of stories, provides a fascinating look at the impact of history on a single location.

German Roots

The local beer industry is rooted in German immigration, which reached its peak in the 1850s. In the 1840s, Germany suffered a severe economic depression, which halted industrialization and sparked a crisis in the growth of urban jobs. Coupled with crop failures in a region from Ireland to Poland, the depression in Germany led to hunger riots and acts of violent rebellion. Many of those immigrating to Minnesota had been part of what ultimately became a revolution against the autocracy of their homeland. When this 1848 revolution failed, many of those involved were forced into exile to escape political persecution - and many of them came to Minnesota.

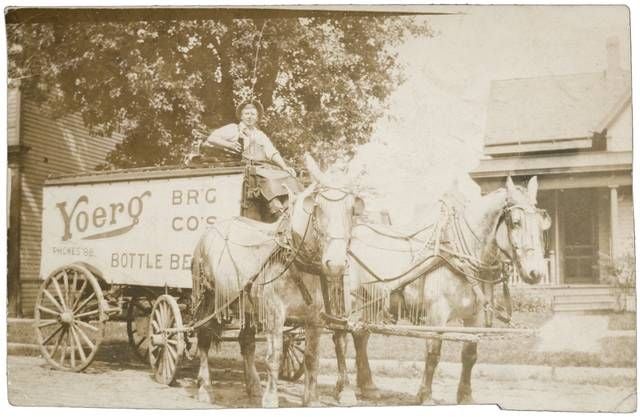

Minnesota proved to be fertile ground for brewing beer - for many of the same reasons it was a great home for Native Americans for thousands of years prior to the colonization of the Americas. Minnesota had productive soil, plentiful fresh water, a farming friendly climate and cool natural sandstone caves, which brewers would later excavate to make lagering cellars. Add to these elements the sudden influx of thirsty Germans, and it's no wonder that brewing got a strong early foothold in Minnesota. In fact, the state's very first brewery, Yoerg Brewing Company, was founded in 1849. That's nearly ten years before Minnesota was granted statehood.

But this tale follows the story of a different brewery. Or rather, a different location.

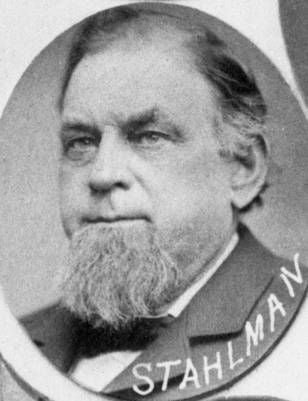

Christopher Stahlmann & the Cave Brewery

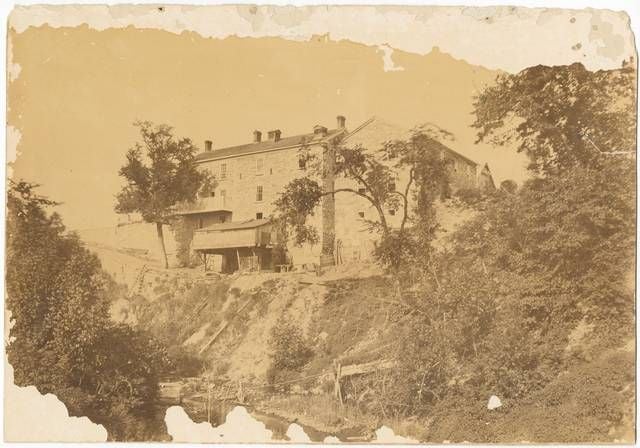

Our story has to do with one location, in what is now Saint Paul's West 7th neighborhood. Founded in 1855, "Cave Brewery" saw early success. Propelled by the power of the Mississippi River, which allowed the brewery to ship beer to ports as far south as Memphis, the Saint Paul operation swiftly became the state's largest by 1860. But the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 put a quick end to the flow of German beer to the South.

By 1883, Cave Brewery nearly faced a premature end when the owner, Bavarian-born Christopher Stahlmann, and all three of his sons died from tuberculosis within 10 years of one another. Just a year prior to the death of the family patriarch, Prussian physician Robert Koch made public his finding that, contrary to popular belief at the time, the disease was not genetic. Despite his discovery that TB was contagious through airborne pathogens, an effective treatment would not come for another 50 years.

Following the death of the Stahlmann men, the oldest brother Henry's widow, Anna, married a man named Frank Nocolin, who took over the company in 1898. The renamed St. Paul Brewing Company struggled for less than three years before being sold to Jacob Schmidt in 1900.

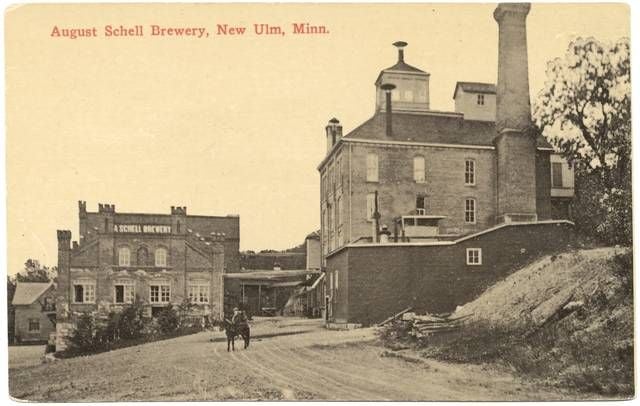

From Schell's to North Star: Jacob Schmidt

Bavarian-born Jacob Schmidt immigrated to America at the age of 20, and after spending a few years working for breweries in New York and Milwaukee, he relocated to Minnesota to work for the August Schell Brewing Company in New Ulm, one of the settlements at the center of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Eventually, he ventured to Saint Paul to take on the role of brewmaster at the operation owned by his friend, Theodore Hamm, who had inherited the business from a gold-seeking associate who died in California. But Schmidt wanted a brewery of his own, and in 1884, he purchased a half interest in the burgeoning North Star Brewing Company.

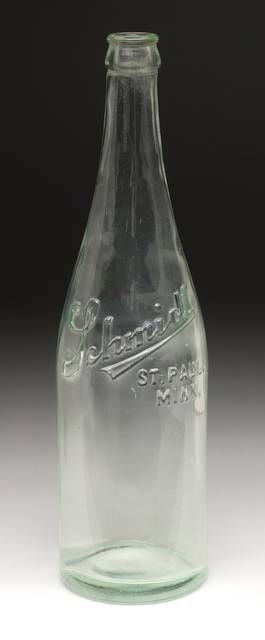

Schmidt's skill as a brewmaster led North Star to become the second-largest brewery west of Chicago, making it a direct competitor of Hamm's. In 1899, he transferred partial ownership of North Star to a new corporation headed by his son-in-law Adolph Bremer and Adolph's brother, Otto. The brothers would later go on to found Bremer Bank. That same year, Schmidt replaced the North Star sign with one that bore his own name, the Jacob Schmidt Brewing Company, but just one year later, the entire complex burned to the ground (though the remains of the aging cellars can still be seen at the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary). Undaunted, the firm purchased The Cave Brewery / St. Paul Brewing Company in the West 7th neighborhood in 1900.

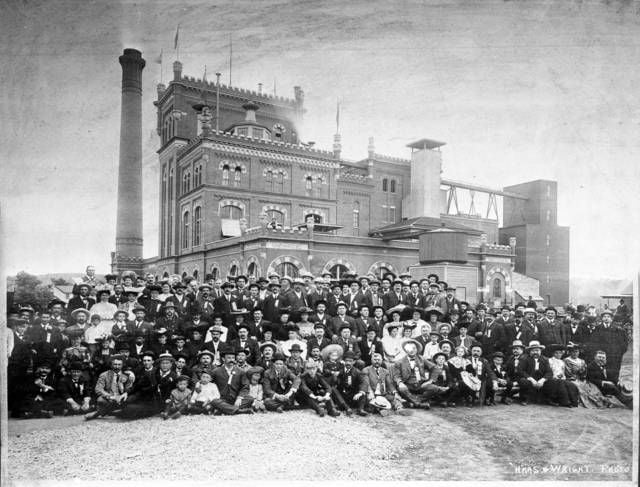

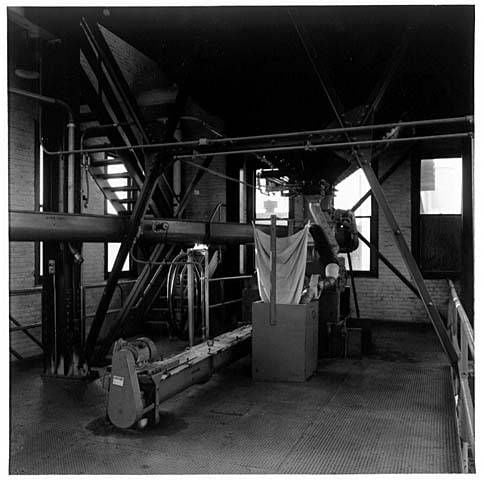

Finding the Stahlmann brewery in a woeful state, Schmidt and the Bremer brothers opted to rebuild the complex with the help of rising Chicago architect Bernard Barthel. The brief was simple enough: Construct a medieval castle on the outside and a modern, streamlined brewery on the inside.

Life was not always foam and fun for Germans in Minnesota. Learn about Minnesota's Commission of Public Safety, the watchful and dangerous eye that Germans found themselves under during World War II.

Growth, Prohibition, WWI and Kidnappings

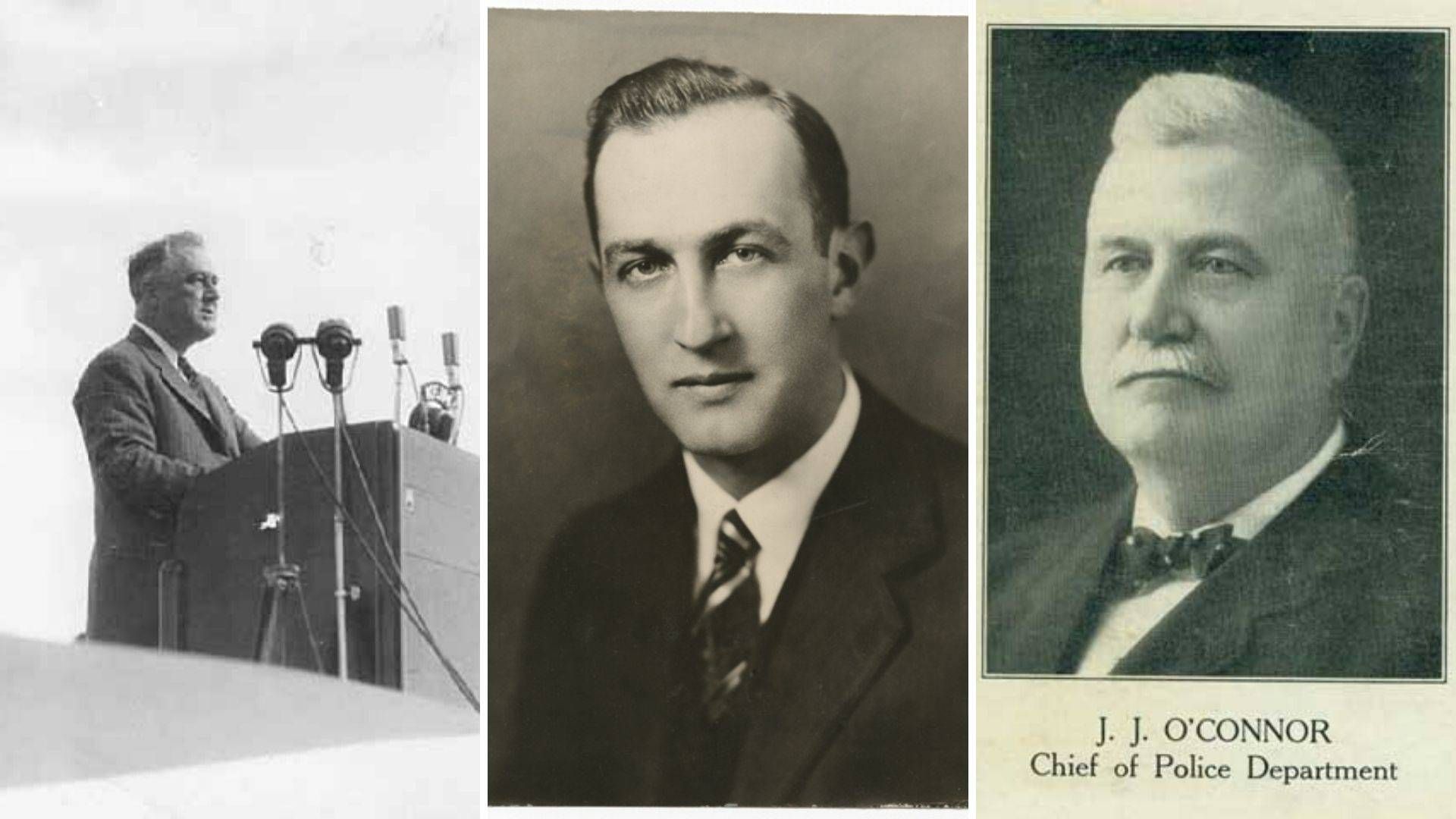

Following Jacob Schmidt's death in 1911, the Bremers took full control of Schmidt brewery, which continued to grow, becoming the country's seventh-largest by 1936. Production even marched on during Prohibition by making nonalcoholic beverages and near beers. The brewery's ongoing success brought both benefits and bad luck to the Bremer family. A close relationship with Franklin Delano Roosevelt led to a fortuitous government contract to supply beer to soldiers during WWI. But this relationship also came into play with a high-profile kidnapping.

In June 1933, the infamous Barker-Karpis gang kidnapped William Hamm, Jr., heir to and president of Theodore Hamm's Brewery. The kidnapping was on the front page of newspapers across the country and broadly exposed Saint Paul's political corruption. A few days later, he was returned in exchange for $100,000. Corrupt Saint Paul Police executive Tom Brown received a quarter of the ransom for his help in the kidnapping.

Emboldened by their success, the Barker-Karpis gang went on to kidnap Edward Bremer, son of Schmidt owner Adolph, a mere six months later. But the Bremer's relationship with President Roosevelt meant that the full force of the government crashed down on the gang - and ultimately on the corruption in Saint Paul. FDR talked about the kidnapping in one of his fireside chats and unleashed the FBI on the Barker-Karpis gang. These two kidnappings were instrumental in the gang's demise - and to the toppling of the "O'Connor System" in Saint Paul, which allowed known criminals to live in the "Saintly City" as long as they obeyed the laws.

Learn more about the O'Connor System and why it made Saint Paul a "good place for bad guys."

The Shakeout: The Fall of the Little Guys

Beginning at the end of World War II, the brewing industry across the country saw a "shakeout" where large national beer companies began entering local markets, heavily investing in advertising and undercutting the prices of local brews. It was during the 1950s that Schmidt - along with many other regional breweries, including Grain Belt - was acquired by a couple of out-of-state companies: first by Pfeiffer Brewing Company, which went bankrupt after 18 years with the brand, and then by G. Heileman Brewing Company.

Though they saw some success, Heileman was the victim of a hostile takeover by the infamous Australian businessman Alan Bond in 1987. When Bond's empire crashed - in part due to the recession of the early 1990s that effected much of the world - Schmidt suffered from the fallout.

In 1990, production at the West 7th location ceased for the first time in 135 years.

A Last Gasp: The Minnesota Brewing Company

In 1991, a group of local investors reopened the Schmidt Brewery complex as "The Minnesota Brewing Company," replacing the iconic flashing "Schmidt" sign that connected the brewery to the grain silos with a non-lighted "Landmark" banner to commemorate their flagship brew. Landmark beer was a flop. The company's other beers - including Pig's Eye Pilsner and the revitalized Grain Belt - saw some success and, by the late 1990s, the operation even ran near capacity, producing 1.2 million barrels a year.

But the success did not last. Too small to focus on local craft brews and too large to produce on a national scale, The Minnesota Brewing Company officially closed in 2002.

Strange Change A-Brewing

The new millennium brought a confusing change - and a new kind of brew - to the Schmidt Brewery location. The Gopher State Ethanol Company moved in and began producing industrial-grade ethanol on the site. Not surprisingly, the noise and smell, among other factors, triggered an immediate, negative reaction to the company from its West 7th neighbors. In 2004, after many complaints and lawsuits, Gopher State Ethanol officials filed bankruptcy and liquidated its assets - including the brewery building.

Today

Like many of the Twin Cities' most historic buildings, the brewery's Gothic brewhouse and bottling house are home today to low- to moderate-income artists. The Schmidt Artist Lofts, revitalized by Plymouth-based developer Dominium, are made up of 260 apartments and townhouses. In 2018, the complex added a new attraction in a former Schmidt outbuilding: Keg and Case West 7th Market.

Perhaps a callback to the brewery's German roots, a full-scale replica of the iconic "Schmidt" sign was recreated and lit for the first time during "GermanFest" on June 21, 2014.

Next time you meander around Saint Paul, peer up at these illuminated red letters and remember that history is all around us. The steps we take today leave footprints for the historians of tomorrow, who will likely chronicle the next chapter in the Schmidt site's story.