Discover the Origins of Minnesota's Own Grand Racist Opera

Forbidden. Forgotten. For real?

This is the weirdest story you'll probably learn for a while. And yet it's all true.

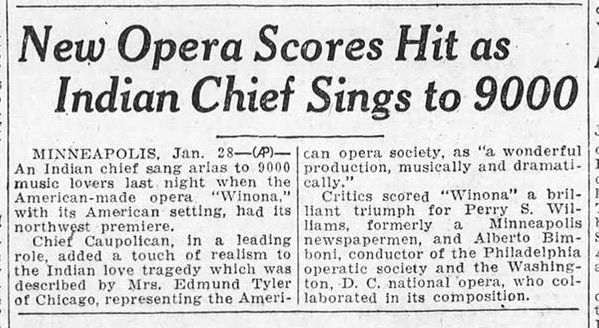

In 1928, Minnesota hosted an original opera performance attended by nearly 10,000 people in one night. The who's-who of Minnesota was in attendance - many of them had been even more involved through any of the countless opera committees formed across the state to help organize and promote the big event. It was such a spectacle that it disrupted railroad traffic, dominated local newspapers and even made it into Time Magazine. The composer was Italian by birth, but the librettist was a Minneapolis newspaperman, and a major player in Republican politics and civic life. The story was set in Minnesota, and the stage of the massive auditorium was transformed to look like the rocky bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River in the southern part of the state. By all accounts, Alberto Bimboni and Perry S. Williams' Winona was an absolutely epic performance.

So, what's the problem? Well, "Minnesota's own grand opera"—and the entire musical genre from which it sprang—is really, really problematic.

Watch this (it's a wild ride and well worth your time):

What? How?

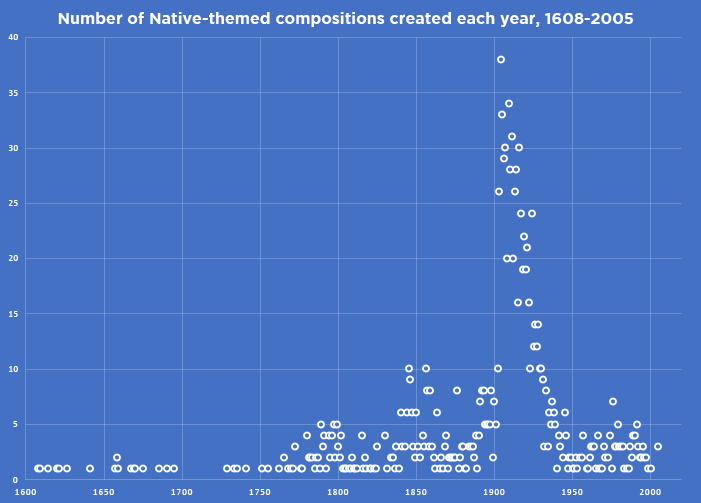

Musically, white composers had been evoking Native people for centuries, but that escalated drastically near the dawn of the 20th Century, as the chart below shows. A small but exuberant cluster of American composers—in an idealistic urge to create a uniquely American genre—sucked Native American musical elements out of their living cultural contexts (with the help of anthropologists and ethnologists) and wove them into "new" compositions as their own original work. While music of this "Indianist movement" was very publicly marketed as having Native origins, it was often presented with little-to-no context about the indigenous societies from which its influences sprang, or about the sacred or secular meaning it might have had for them.

Heretofore, white Americans had seen Native people as living communities, albeit as inconvenient obstacles to Manifest Destiny, at first wild and dangerous, and then eventually deserving of pity. By the late 1800s—as land theft, disease, wars and scarce resources diminished the threat they represented—Native societies were increasingly viewed as a quaint, noble, blessedly-past-tense entry in the history books of a nation on the move.

The Noble Savage myth came to life as white America hurried to bring the uncomfortable "Native chapter" of its own history to an end. Beginning perhaps with Longfellow's "Song of Hiawatha," white creators in arts and popular culture began to mythologize Native cultures in almost archetypal ways. The feathered headdress of the Plains tribes came to symbolize all things Indian, just as much as a toga indicated Greece or Rome, or a horned helmet evoked a Wagnerian Germanic or Viking scene. For these opportunistic makers and shakers, Native culture was ready for artistic commodification.

You can’t hurt history’s feelings. But you sure can hurt people.

Reservations moved Native populations out of the way of "progress" and out of the public consciousness. Railroads, telegraph, telephone, automobile, airplane: Every new invention shrank the vast American landscape, and further buried the idyl of Native pastoral and nomadic living squarely in the past. An aggressive assimilation program by the United States federal government ramped up this process through boarding schools, prohibition of sacred ceremonies and traditions, and a forceful move to eradicate indigenous languages. The nascent field of cultural anthropology roared to life just in time to apply white scientific principles to the documentation of Native cultural artifacts and activities before they disappeared forever. Indeed, American anthropology was utterly defined by white researchers having such ready access to Native societies as ethnographic subjects. It took only some well-intentioned music lovers—heeding Antonin Dvorak's call to find a uniquely American musical voice—to take that ethnography into the strange and problematic realm of this story.

This is a complex, nuanced story without many simple answers.

One dominant culture’s passing curiosity with the symbols of another oppressed culture makes for hollow art. Yet the work of ethnologists like Minnesotan Frances Densmore preserved Native cultural activities that would have otherwise been lost. Of course, preservation was only necessary because of centuries of brutal genocide and oppression, and yet preserve some they did. Culture is, of course, a vast resource for artistic influence, and an organic synergy can be exciting and innovative. It’s quite different when the "influencing" is performed so surgically, so methodically, so intentionally and so one-directionally.

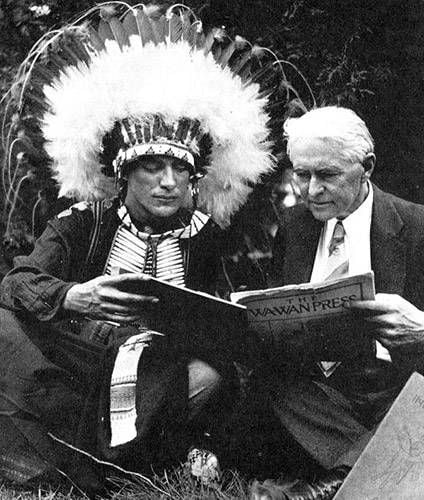

The lumping of Native cultural elements as meaningless, interchangeable parts is also problematic. For his Minnesota-set opera Winona, Alberto Bimboni blended elements from Dakota, Lakota, Ojibwe and other cultures without a second thought, dumping them in a bowl and stirring as if to make bread. Many Indianist composers were more interested in what sounded "Indian" than the indigenous cultures from which each element came from and what it meant. By contrast, Minnesotan composer Arthur Farwell was a purist in his devotion to authenticity, resisting the urge to compose music that sounded “Indian.” His goal was to liberate American music from the dominance of European influence, and he used Native American themes, African American spirituals, Mexican melodies and cowboy tunes to do it. As goals go, that actually sounds pretty…cool?

In modern context, this story's legacy remains unsettled. Choctaw ethnomusicologist Tara Browner critiques Indianist composers for treating Native culture as a naked raw material, though she says that Farwell was less guilty of this than most. Music critic Joe Horowitz sympathetically branded Farwell “America’s Forbidden Composer,” whose genuine musical genius is forever stained by the genre. Cherokee pianist Lisa Cheryl Thomas says she loves performing Indianist work, especially Farwell's, because it connects her with her ancestors’ music. Perhaps most significantly, some Native communities are using Densmore’s work to reclaim and relearn their sacred songs and rituals in the 21st Century.

Minnesota's fingerprints are all over this strange true story, a dangerous and complex cocktail of racism and romance, genocide and genius, encounter and erasure, preservation and pain. As Minnesota stories go, this might not be one we're particularly proud of. But it is definitely one worth knowing.

APPENDIX

Since not everything fit into the video or this article, here are some more rabbit holes in which to lose yourself:

Amazing resources from The International Center for American Music (from which vast amounts of information and images were derived for this video and article):

- Video performance of an excerpt from Winona

- Winona Conference Papers

- Gretchen Peters on Importance of Real Indians in Winona

- Academic paper on Bimboni, Winona, et al

Other resources:

- Chief Caupolican performing in Whoopee! (1930, colorized)

- A deeper story and chronology of Frances Densmore, via MPR

- A list of all Native-themed compositions (data source for chart at top)

- The amazing story of Native opera composer and trailblazer Zitkala-Sa, via PBS

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

Twin Cities Producer Kevin Dragseth has a keen interest in uncovering stories that "tangentially Minnesota" in nature. In a recent historical adventure, he wondered: Can Minnesota lay claim to both King Kong and Super Mario?

When Land O' Lakes decided earlier this year to remove the iconic Native American maiden from its packaging, many celebrated the move. After all, members of the public had called on the company for years to remove what they considered racially stereotypical and culturally appropriated. But Mia, as she is known, was given a refresh by Red Lake Ojibwe artist Patrick DesJarlait in 1954 - and his son, the artist and activist Robert DesJarlait, has mixed feelings about the company's decision. So we wondered: Is Mia a racist trope or a symbol of Native pride?

Discover how Minnesota-based brothers Micco and Samsoche Sampson are revitalizing another Native American tradition, the art of the hoop dance, with a dash of influence from hip hop.