Confused About the Saint Paul Winter Carnival's Mythology?

History sets the record straight.

In Minnesota, we willingly engage in verbal sparring matches when East Coast reporters get it wrong about our great state. Remember when Washington Post reporter Christopher Ingraham had the gall to proclaim Minnesota's Red Lake County "the absolute worst place to live in America"? Minnesotans rose up in defense: Clearly, he had never visited Red Lake. And when he did, he decided to move his family there.

East Coast reporters: +0. Minnesotans: +1.

Then there was #grapegate. A seemingly innocent effort by the New York Times to gather iconic recipes representing America's 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico resulted in raging backlash when grape salad was crowned the winning traditional recipe of Minnesota. Hot dish with cream of mushroom soup and tater tots, sure. But grape salad? Nope. Just nope.

East Coast reporters: +0. Minnesotans: +2.

But that fine tradition of Minnesotans setting "hoity-toity" East Coasters straight is also the reason why we have the Saint Paul Winter Carnival, the oldest wintertime festival in the U.S. As the story goes, in the fall of 1885, a gaggle of Eastern newspaper writers visited Minnesota, only to return home and write about the state as a carbon copy of Siberia: in other words, a wasteland unfit for human habitation. To set the record straight, a group of prominent business leaders gathered to hatch a plan to prove the Eastern newspapers wrong - and the concept for a festival celebrating the glories of Minnesota winters was born.

As with all things meant-to-be, the timing was just right. Canadian city, Montreal, already had a winter festival - but due to a small pox epidemic, city officials were forced to cancel the celebration, which freed up Montreal's ice palace architect extraordinaire, Alexander Hutchinson, to design Saint Paul's first winter monument. Stretching 106 feet into the thin, winter air, that first ice palace was the largest ever built.

But naturally a grand construction worthy of Minnesota's icy splendors also required a story to go with it. Tasked with filling an ambitious, month-long agenda of events, the original organizers had enough on their harried plates - so they passed along the assignment of fleshing out the Winter Carnival Legend to Delos Monfort, president of Saint Paul's 2nd National Bank. And he attacked his mission with imaginative aplomb.

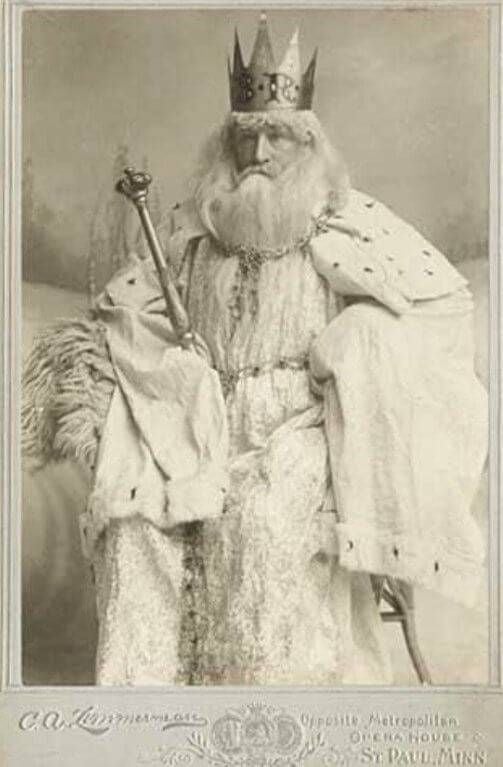

But still. With an Ice King, a Fire King, myriad queens and princesses, a massive Royal Court, along with someone named Klondike Kate, it's easy for modern Minnesotans to feel thoroughly confused. So without further, adieu, here's a rough sketch of the mythology that Monfort created and how it played out at the 1886 Winter Carnival.

Chapter One: Out of Thin Air, a Royalty is Born

In a time before time, Astraios, the god of Starlight, and Eos, the goddess of the Rosy Fingered Moon got married and had five mighty sons. Their eldest, Boreas, became King of the Winds - and with his new role, he assigned each of his brothers the special powers to control a particular wind. Good news for them (except for Euros, who was charged with the "irresponsible" East Wind). Because the five brothers were godly creatures filled with wanderlust, they traveled the world on the winds and took an inventory of the globe's most magnificent places.

But when Boreas first landed in the winter wonderland of Saint Paul, with its seven stunning hills, he was smitten. Remember: This was before the term "polar vortex" entered our cultural Minnesota lexicon.

Because there was no place on earth more fair than Saint Paul, Boreas decided to make our capitol city the seat of his exceptional domain. And because every newly formed kingdom needs a giant party, Boreas began his reign with a Winter Carnival celebration and gave the good people of Minnesota ample opportunity to feast and frolic, to play baseball on skates and to shoot striped-blanket-clad people high into the clouds on hand-held trampolines.

Chapter 2: The Enemy at the Ice Palace

But like most good kings, Boreas had a rival, a character given the truly horrible name of Vulcanus Rex, also known as the Fire King, who wanted nothing more than to defeat the new monarch of Saint Paul. Fun fact: During that Winter Carnival of 1886, legend creator Delos Monfort played the part of Vulcanus Rex.

This is the point in the story when we pause and question Monfort's aim: Can you really rally a population of people who complain about nine months of winter to turn against the king who promises the summer in favor of the other king who prefers endless winter? We'll leave that for you to decide.

Still, Vulcanus Rex posed a serious threat to Boreas' reign of merriment and toboggan races down Ramsey Hill. Before the Fire King had a Krewe (that term wasn't used until 1940), he had a crew of 2,000 soldiers, mostly plucked from toboggan and snowshoe clubs, that threatened to break through the icy walls of Boreas' glorious ice palace.

Chapter 3: Boreas Means Business

Before the Ice King and the Fire King face off, allow us to step back and describe, in the words of historian Patrick Hill, writing for the Pioneer Press, the astonishing fortress Montreal architect Hutchinson created to herald Saint Paul's King of Winter: "The palace grounds were ringed by a fence and hundreds of evergreens creating a defensive barrier. On the western edge a six-track toboggan slide descended Cedar Street, creating another hindrance for any potential attackers. The only practical entry to the compound was at the southern end, at the termination of Minnesota Street, through a massive 75-foot-wide ice arch flanked by two 40-foot ice towers that would be guarded by the King’s sentries when the Ice King arrived."

When Boreas arrived, it was by ice-encrusted train. Once he stepped onto the hallowed ground of his wintertime kingdom, he was ushered onto a sleigh, pulled by 12 white horses, that would take him to City Hall, where he swiftly demanded the keys to the city. The mayor acquiesced. Some Minnesotans in the crown booed. Some of us, after all, are truly fair weather fans.

A parade carried Boreas to his ice fortress, while some in the crowd set off fireworks as signals of distress to come.

Chapter 4: Peace and Parties? Boring.

Of course, a kingdom in a state of revelry, peace and splendor will soon face an epic battle that threatens its ethereal serenity - we learn this at a young age in fairytales and cartoons. And sure enough, that's precisely what happened to the Kingdom of Saint Paul. On February 4, 1886 - just two days after the arrival of Good King Boreas - Vulcanus Rex and his army carried out a plan to attack the Ice Palace.

With 100,000 spectators awaiting the battle, the Vulcanus Rex made a grand entrance on his Fire Chariot, a float bedecked with a throne and four pillars that shot flames like angry volcanoes. Upon Boreas' refusal to surrender, the Fire King sent his forces forward, armed with 15,000 Roman candles, and the spectacle that ensued would make modern crowds roar. Patrick Hill writes, "As the fireballs arched upward against and over the palace walls, the castle answered with mortars launching fireworks into the sky, while the walls of the shining palace flashed alternately between white, blue, crimson and emerald electric lights within. The shouts of the combatants and smoke from their weapons rent the air. Such an event had never been seen in America before."

After 30 minutes of fantastic showmanship, the Ice King and the Fire King reached an armistice, and good Minnesotans were discharged for a celebration downtown. Newspapers all over the country chronicled the crowning achievement of the Winter Carnival and heaped praise on the event as a truly unrivaled experience.

East Coast reporters: +0. Minnesotans: +3.

Chapter 5: A Reckoning

Still. Boreas had to be defeated, despite his grandeur, despite his love for the City of Saint Paul. Otherwise, continuous winter would envelop Minnesota in snow and ice - and the madness of spring would never again produce a riot of blooming and greening and awakening.

A week after that first battle, a second effort was in the works. This time, Winter Carnival organizers called on a group of soldiers that President Abraham Lincoln had dubbed "the mightiest force on earth": a group of Union Army soldiers scattered across the nation and the Great Plains who formed the Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans organization that made appearances at parades and civic events. Now they were called upon to defeat the Ice King.

On February 12, 1886, 2,000 soldiers and their sons gathered in Rice Park with their resplendent uniforms and muskets loaded with blanks, and began their march toward the Ice Palace. Vulcanus Rex's army already flanked the castle, and when the Grand Army of the Republic soldiers arrived, they swiftly parted to let them through. The crowd grew silent in anticipation of what would happen next.

The scene that followed must have thrilled and terrified the 100,000-strong crowd that showed up that day. Again, Patrick Hill writes, "The castle walls again flashed electric colored lights in defiance, joined by flashes from the turrets. The Emmet Artillery of the Minnesota National Guard joined the battle, launching fireworks above the castle. Special wires had been attached to the castle walls, and now fire bombs were launched along the cables timed to explode as they hit the ice blocks. The castle answered with fireworks of its own. The tremendous tumult of noise and light and smoke from the battle was joined by the enthusiastic throaty approval of more than 100,000 joyous onlookers."

Then a group of soldiers climbed the east wall of the palace, briefly taking the battle inside before the gates were flung open and a rush of additional soldiers charged inside. Only moments later, the crowd watched the Ice King's Polar Bear Flag drop in defeat from the highest turret of the palace. Boreas had lost the battle, but he and his Royal Court were granted pardons as long as they promised to leave fair Saint Paul.

With the soaring success of the first Winter Carnival in 1886, the 1887 and 1888 editions were equally popular, generating rave reviews and bringing an economic boon to Saint Paul, despite the arctic blasts of winter.

East Coast reporters: +0. Minnesotans: +4.

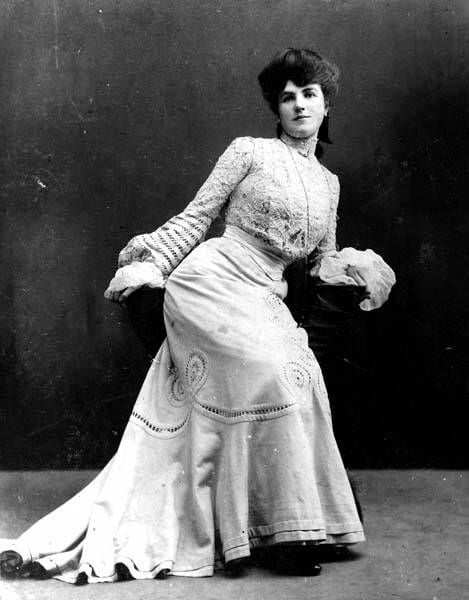

Chapter 6: Who in the World Is Klondike Kate?

The real Klondike Kate, a.k.a. Kathleen Eloise Rockwell, found fame as a dancer and vaudeville performer who took the Klondike Gold Rush circuit by storm. And her connection to the Winter Carnival is mercurial at best. Today's organizers write, "When the Saint Paul Winter Carnival began, Klondike Kate could easily have been the first to entertain at the Casino. Although it is not known exactly when Carnival began hiring entertainers, it is known that the last entertainer hired was in 1961, and she was known as 'Klondike Kate.'"

Did the real Klondike Kate ever venture north for the Winter Carnival or was it just her legend that traveled on her behalf?

We'll never know. But today, a new Klondike Kate is chosen every January, and she serves as the reigning queen of cabaret performances during the two weekends of the festival. A group of women who have played the part in past carnivals now form the Royal Order of Klondike Kates - and they make appearances throughout the year, singing on parade floats and championing a positive perception of Klondike Kate's legend.

It may be cold in Saint Paul. But we've found a way to cope with that. Coupled with the Winter Carnival's ice palaces and sculptures, toboggan races and parades, the event's winding mythology provides a warm balm to winters in the Bold North.

Discover more about The Legendary Saint Paul Winter Carnival by watching a documentary film produced by Twin Cities PBS.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.