We are stardust, we are golden

We are caught in the devils bargain

And we got to get ourselves back to the garden

- “Woodstock” by Joni Mitchell

You know, there was another place besides Woodstock in 1969 that was steeped in controversy, had 500,000 Americans, ever-present helicopters, tons of drugs and lots of mud.

Vietnam.

Much of the past 50 years has been spent widening the gap between these two different portrayals of America, pitting hippies against soldiers, peaceniks against patriots, the cowardly against the brave. But like so much about the 1960s, the Woodstock-Vietnam dialectic is a lot more nuanced, much more convoluted… A touch of grey if you will.

I say that for two main reasons. One, there were a helluva lot of Vietnam veterans at Woodstock, including several on stage; and two, there were plenty of guys like me who were in Vietnam after Woodstock and considered ourselves part of the Woodstock generation. I know this both from my own experience and from hundreds of interviews with Vietnam veterans about their music-based memories, which became the focus of We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, an award-winning book I co-wrote with my good friend Craig Werner. We discovered that the thread that weaves a tapestry of a more authentic 1960s America is music, the soundtrack that was shared by all of us who listened to the radio, purchased records and albums, went to concerts, strummed a guitar or simply had a song playing in our head.

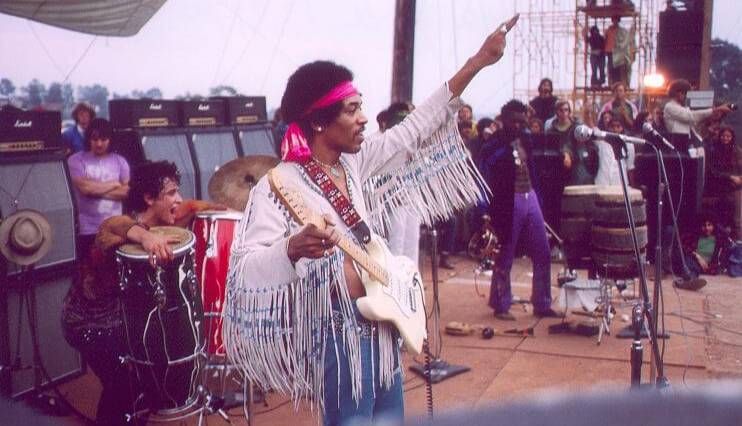

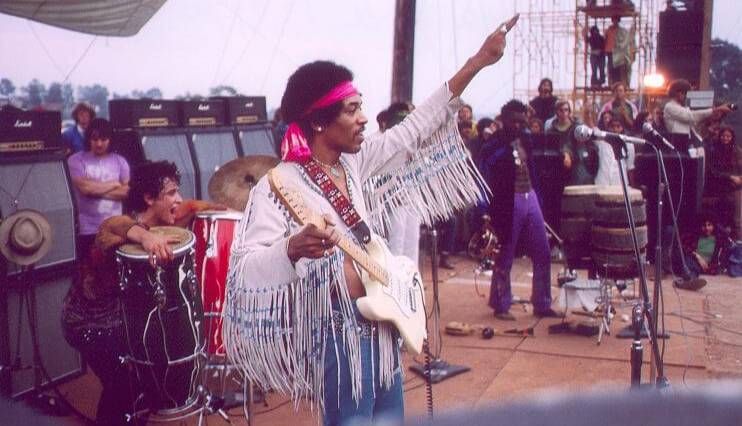

Regarding my first point, veteran performers at Woodstock included Country Joe McDonald - yes that Country Joe - John Fogerty and Doug Clifford of Creedence Clearwater Revival, and three members of the Gypsy Sun and Rainbows band - Billy Cox, Larry Lee and the one-and-only Jimi Hendrix. Lee, in fact, had just returned from Vietnam.

“Man, it was strange,” he recalled. “I’d only been back a few weeks and I’m on stage, and there are helicopters overhead, naked muddy people and Jimi’s guitar sounding like a chopper or an explosion. I had to shake my head to make sure I wasn’t back in ‘Nam.”

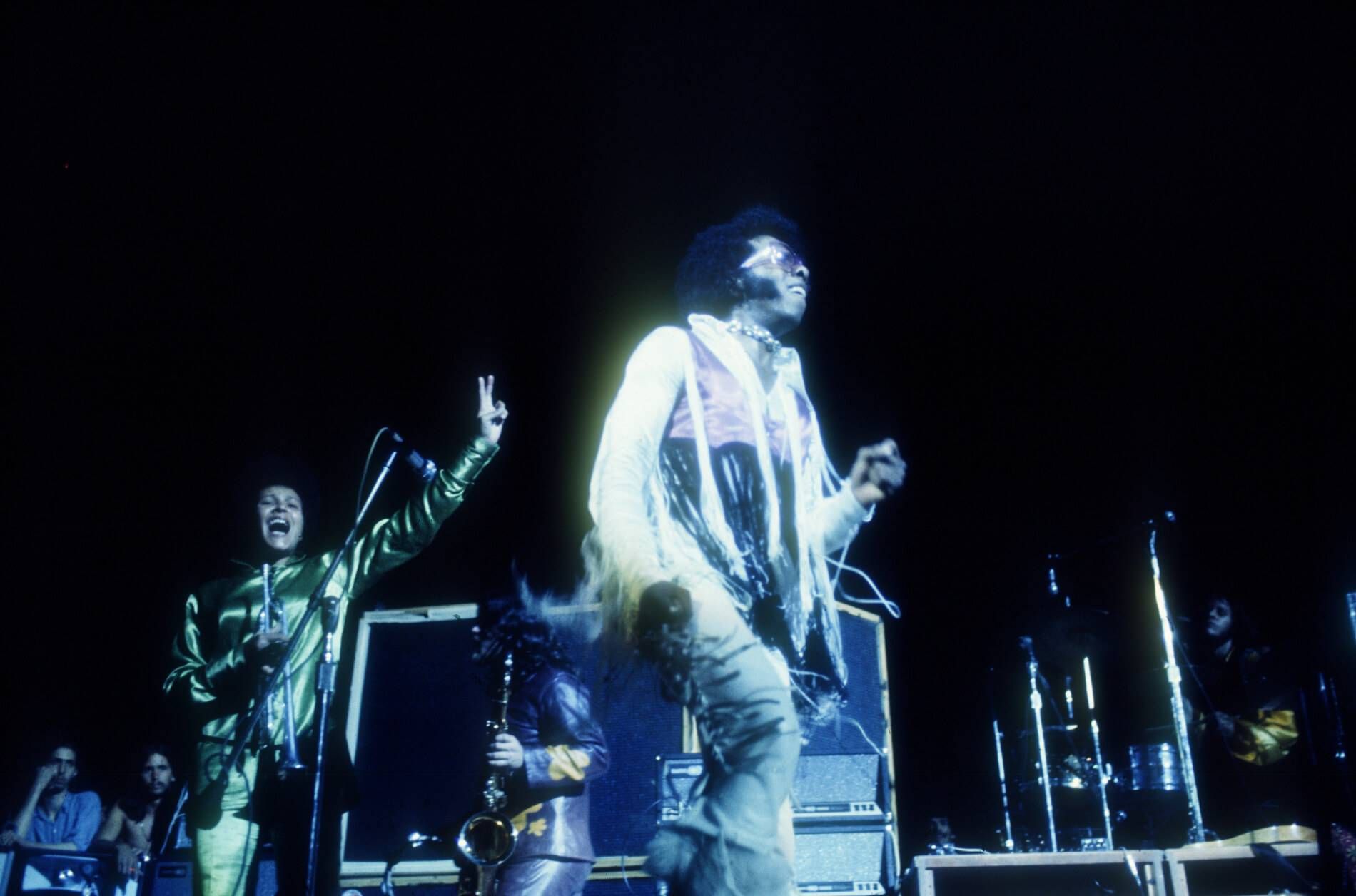

The highlight of the Hendrix performance, maybe of the entire four days of Woodstock, was Hendrix's sequence of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Purple Haze.” Wearing the white fringe jacket, bell bottom jeans and a red-orange headband that became emblematic of the festival, Jimi stepped forward to reclaim the national anthem for the members of his generation who had set out to construct an alternative vision of what a community could be. From the opening notes, Hendrix let loose with a radically innovative interpretation, asking his listeners to really hear a song they’d been exposed to thousands of times. And then, having established the familiar melody, he took the anthem to places it had never been before. A virtuoso of feedback and amplification, Hendrix unleashed a barrage of combat sounds - echoes of the trumpet call to arms and the Navy’s all-stations, evocations of helicopter blades, explosions, machine guns. Chaos that put the listener waist-deep in Vietnam. Hendrix’s Star-Spangled Banner is at once a tribute to the soldiers in Vietnam, living in the midst of those sounds, and a razor-sharp comment on the contrast between America’s ideals and the realities of the war.

There’s no way of estimating how many veterans were in the Woodstock audience, but we talked to a few. Jurgen “Mike” Lang had just returned from his tour as an anti-tank gunner with the 9th Infantry and “was just sitting around when a couple of friends said, ‘Hey, we’re going to New York.’ I said okay, and I ended up at Woodstock. I wound up working at the hot dog stand… It was an interesting place to be.”

New York City native Anthony Borra, who served with the 463rd Tactical Wing in Saigon and Cam Ranh Bay, told us that Jimi’s guitar “put me right back there [Vietnam]. It’s like ‘Beam me up, Scotty boy’ and that song sure beams me right back.”

And the 1st Air Cavalry’s George Gersaba, Jr. offered one of the best summations of the veterans’ affectionately bemused response to Woodstock. “We Cav troopers were laughing at the announcer in the Woodstock movie congratulating the crowd for surviving three days in the field,” he smiled.

Meanwhile, Dennis DeMarco, who was in Vietnam at the time, found a “high-ly” unlikely way of connecting with the spirit of the event. “After pining in misery for a few days,” DeMarco recollected about missing Woodstock, “I sent some of the best marijuana I’d ever smoked to my friends, and they could take it to Woodstock. A part of me would be there for all to enjoy.”

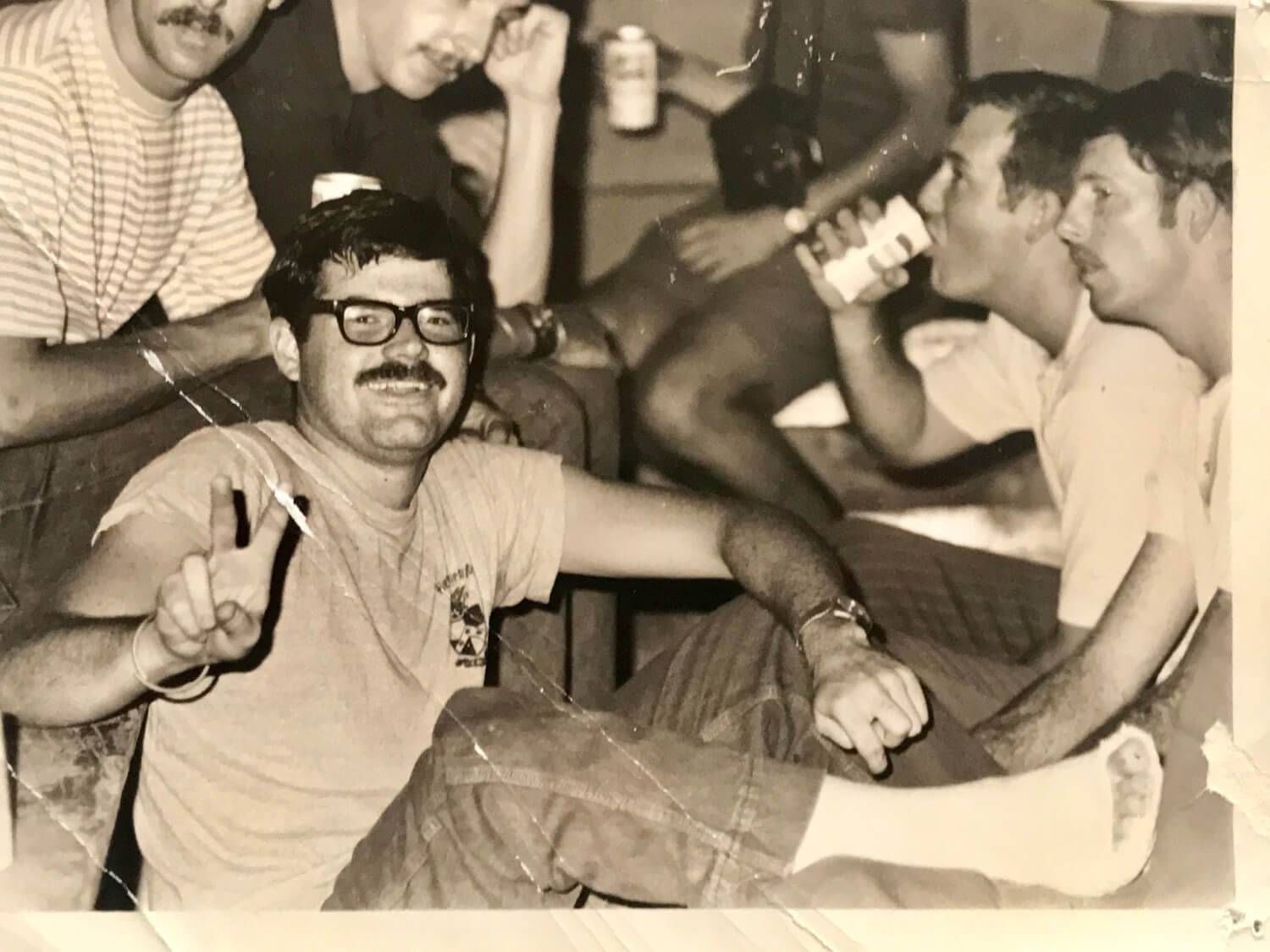

Of course, not all soldiers, or veterans, were as inclined to feel a cosmic connection with the crowd at Woodstock. Again, that’s the complicated nature of the time - veterans were there, they performed, they listened, they sang, they danced. At the same time, many Vietnam veterans and soldiers detested what was going on. Or, like me and Gordon Smith, took our post-Woodstock ambiance to Vietnam.

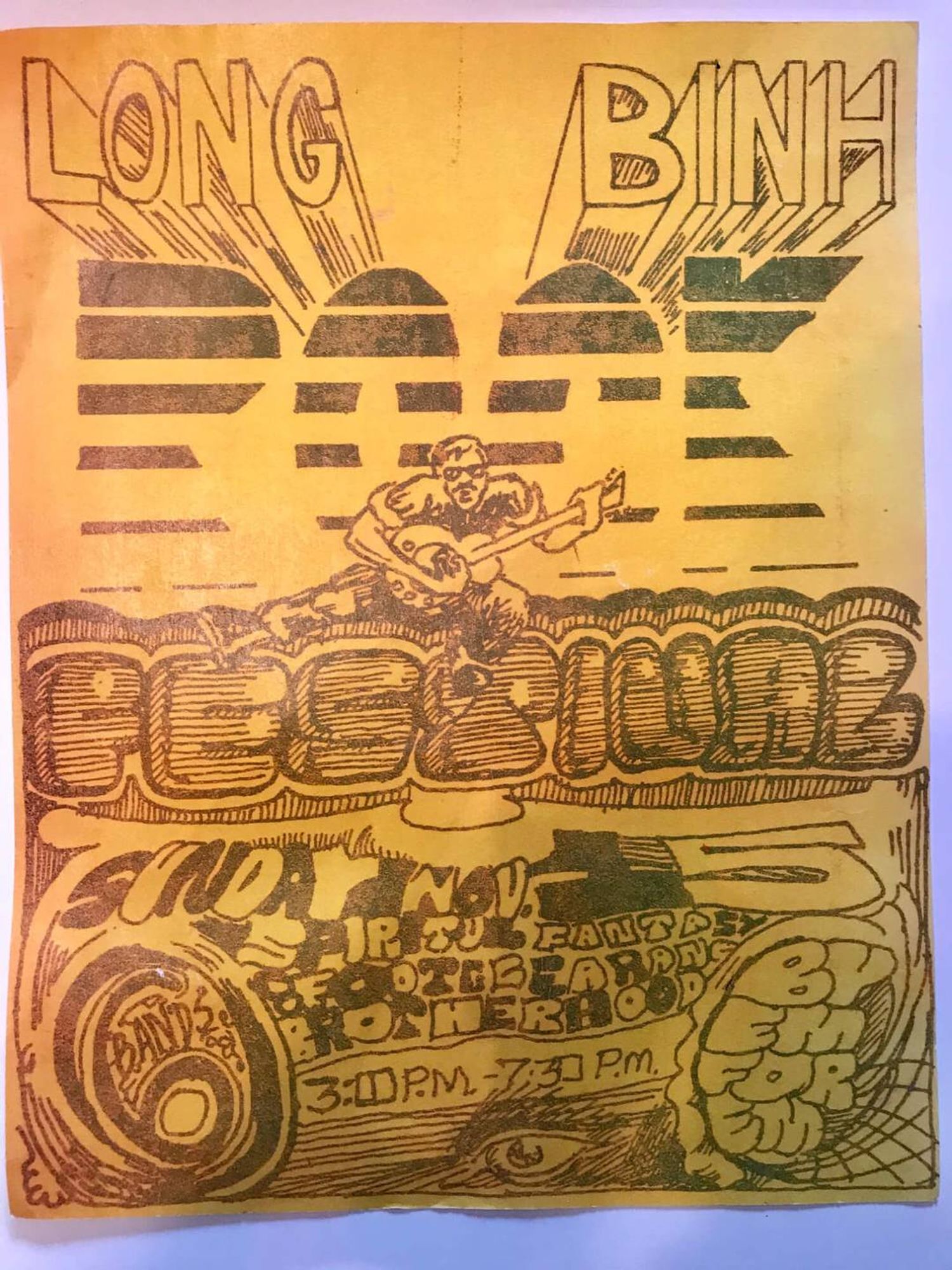

Smith served as a mission coordinator with the 834th Air Division at Bien Hoa in 1970-71. Armed with tapes of albums by Ten Years After, Blind Faith, and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Smith caught wind of an event designed to bring the spirit of Woodstock to Vietnam. “I’d gotten there in August,” said Smith, as he handed us copies of a poster for the “Long Binh Rock Festival” scheduled for November 15, 1970. “I got one of these posters and showed it to the Army guys and said, ‘let’s go.’ I couldn’t go with the Air Force guys ’cause if they told people I was smoking dope, I’d be up a creek.

“So that morning we got up real early,” Smith continued, “brought along some dope and drove to Long Binh. We get to this huge amphitheater, and there are only 20 or 30 guys sitting around. ‘What happened?’ we ask them, and they say, ‘The commander cancelled the concert because he was worried there’d be too many drugs there.’

“Of course, there would be,” Smith smiled.

I arrived at Long Binh a few days before the aborted “Long Binh Rock Festival.” But bless their hearts, the Army would give us Woodstock after all - the movie, that is. I saw it a bunch of times in Vietnam, usually stoned, and enjoyed the hell out of it. It was as if, for a few hours, we were all there, Woodstock, and not here, Vietnam. By far the most memorable showing came one night at a nice indoor theater on the nearby Bien Hoa airbase. A bunch of us were there, zonked, standing on our chairs when Sly and the Family Stone agreed to take us “higher.” It was electric and it was loud. So loud that we couldn’t hear the sirens warning us of an enemy mortar attack. A group of MPs entered the theater and ordered us out. But Sly was still proclaiming, “I want to take you higher/baby, baby, baby, light my fire.” We didn’t want to leave.

But we did after the MPs had the projector turned off. They gave us hell, but let us return to Long Binh. All but one of us, that is, a Spec. 4 named Jackson, who, for all I know, is still standing on his chair at whatever is Bien Hoa airbase, screaming “Higher!”

Woodstock and Vietnam. In the end, we were all caught in the devil’s bargain.

This story is part of the collection The Call to Serve: Stories of Sacrifice, War and the Way Home, which was funded by the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation.