All You Ever Wanted to Know About Forest Bathing

...or if that headline is too bougie for you, how about, 'The benefits of a slow walk in the woods.'

During what promises to be a difficult COVID winter, I'm living with a new mantra: Always be up for new outdoor adventures. Let me preface this by saying that I’m up for new outdoor adventures that don’t require a lot of skill, risk or money.

I'm 45 years old. If I haven't yet learned to climb rocks, do parkour or ride really fast on a bike down a wooded path, it's safe to assume it's not going to happen. Though I firmly believe this is a time when I should be getting outside and into some wide open spaces more often, I also believe this is definitely a time where I shouldn’t be taking up valuable medical space or attention nursing a broken ankle, snapped ACL or concussion. I’m not a risk-taker. Never have been, never will be. I like to keep things slow and steady.

YOU CAN TAKE A FINN OUT OF A SAUNA, BUT YOU CANNOT TAKE THE SAUNA OUT OF THE FINN

In an effort to get out of my home office and away from my computer, I starting looking for something new I could do at an area park. Something safe, cheap and with a low entry point when it comes to skill. I stumbled across an NPR article from 2018. The headline read, "Suffering from Nature Deficit Disorder? Try Forest Bathing." The headline caught my attention for the wrong reason, and that reason revolves around outdoor bathing.

I'm a Finn. My grandparents and father claimed to be 100% Finnish. Were they? I don't know, yet I'm not about to do a DNA test to prove them wrong. I've grown up thinking I'm 50% Finnish and 50% German. As a Finn I've grown up taking saunas. If you just read the word as 'saw-na' go back and ready it correctly, it's pronounced 'sow-na'. There aren't too many ways to make a Finn's skin crawl, but butchering this word is one of them.

What's the best part of taking a sauna? Building and stoking the fire in the sauna stove is good. So is feeling that first, sharp blast of steam as you pour some water on the rocks - but jumping into a lake for a post-sauna rinse, listening to your heartbeat in your ears as your 180-degree body is met with 65-degree water is the best. How do you know you're alive? No need to bungee jump or skydive. Take proper sauna. You'll feel it.

Some might call it skinny-dipping. In Purple Rain, Prince calls it "purifying yourself in the waters of Lake Minnetonka." Finns grow up knowing it's just what you do after you take a sauna. So, when I read about "forest bathing," you best believe I was caught dreaming about a new way to cleanse outdoors. I was a little disheartened to learn slapping myself with cedar boughs while rolling around in the snow was not a part of this type of bathing. And yet, forest bathing ticked the three important boxes of being easy to do, safe to do and cheap to do. So, forest bathing it was.

Now one more time for good measure, it's 'sow-na', not 'saw-na'.

AN IDEA BORN IN JAPAN OUT OF NECESSITY

Forest bathing is an idea born in Japan, which is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, yet one that boasts some very rugged, uninhabited landscapes, varied climates and plenty of access to outdoor space. One just needs to work a bit to get to those landscapes.

There's a good chance if you are in Minnesota right now, you can peer out a window and see some trees. I've never been to Japan, but one can assume that cities like Tokyo and Osaka - like many large cities in America - aren't exactly abundant in natural spaces, a key component to forest bathing.

Shinrin-yoku (shinrin = forest, yoku = bathing) is an ancient tradition that tries to balance the benefits of living in an urban population with the benefits of being exposed to trees. It's a practice that requires people to spend vast quantities of time with trees to gain health benefits from them. To put it another way, forest bathing attempts to explain why people tend to feel better after they've taken a walk through the woods. With the fresh air, dappled sunlight, the sounds of birds, the smell of the trees, the crunch of leaves or softness of pine needles underfoot, the forest can awaken senses that lay dormant while we are in our furnace-heated homes, typing on our laptops, listening to podcasts and living under artificial lights.

Shinrin-yoku also states that, to gain the full benefits of bathing in everything the forest has to offer, one must walk slowly. They must NOT run. I like this. I tend to only run if I'm being chased, and I haven't been chased since I was a kid.

I'm not sure if Dr. Qing Li is the foremost authority on forest bathing but he has written a book on the topic and is quoted in a couple of articles, so let's say he is: “It is important not to hurry on a forest walk. It is not a hike,” Dr. Li writes in his book.

“Walking slowly will help you to keep your senses open, to notice things and smell the forest air.”

I can do this. I can improve my mental and physical health by walking slowly in a forest. Yes, I do realize I'm over simplifying Dr. Li's life work, but for the sake of this article, I'm going to head out into a forest and make note of what I sense and how I feel before, during and after my time among the trees.

THERE IS MORE GOING ON WHILE FOREST BATHING THAN THERE WOULD APPEAR TO BE

Looking back at this video, I simply look like a very old man walking, nay, "gahoofering," through the woods. Don't let this deceive you. Though my pace was sleepy, and my uncoordinated gait was "gahooferish" - as we Heikkilas tend to be - I was fully aware of the sounds and smells around me. The smell of the pines, the scent of decaying leaves, the crunch of the snow and the call of the crows were omnipresent. Being slow allowed me the time to breathe in my surroundings and created an experience that made me feel awake inside.

IF FOREST BATHING CLOSE TO HOME, WILL ANY FOREST DO?

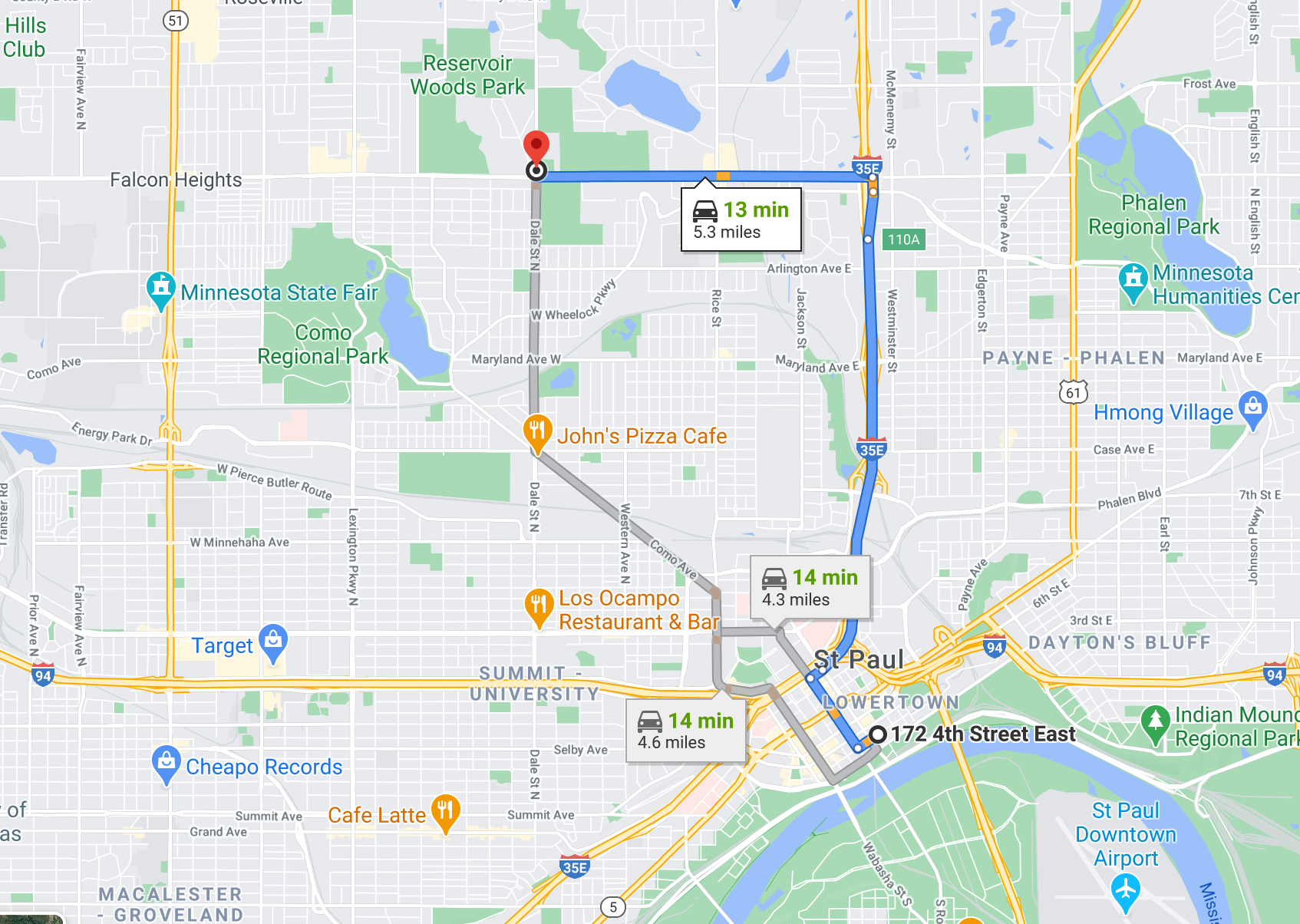

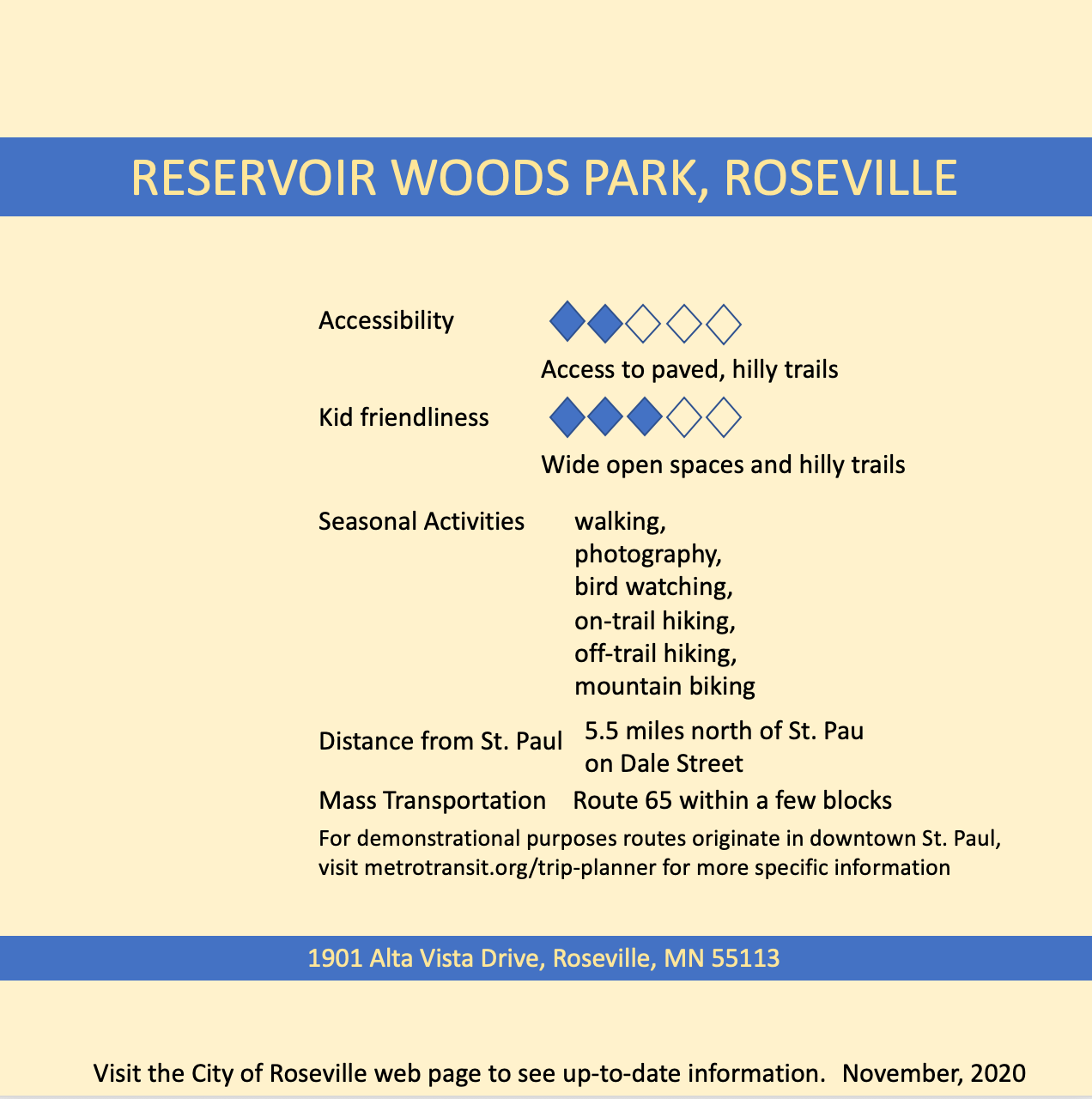

The first forest I stopped at was not a traditional forest in the Appalachian Trail sense of the word; it's a little on the small side. My favorite stand of pines is in Reservoir Woods, a park in Roseville, Minn., so I started there. Dr. Li would agree that this forest is too small. Forest size does matter. Larger forests have, logically, more trees, and the more trees equate to a higher density of phytoncides. If you, like me, did not major in, horticulture or new-age plant science, let me define phytoncides as "antimicrobial allelochemic volatile organic compounds derived from plants." Whatever that means. Let's just go with, "being in the woods is good for you."

While researching the topic, I learned that, aside from being in a forest that is not too small, forest bathing is best done in temperate climates. As it turns out, being cold limits the amount of energy I can spend focusing on the natural world around me. And, if I were moving a bit faster, I would generate some body heat. To this point, let me say: I get it, but, come on now, just layer up and you'll be fine. I wore fleece-lined pants, a long-sleeved t-shirt, a hooded sweatshirt, a wind jacket, stocking hat and my favorite pair of leather choppers with woolen mitts. If you have comparable clothing, the temperature is in the 20s and there is barely a breath of wind, you'll be fine forest bathing in the winter. As a Minnesotan, if I stand around waiting for the perfect weather to do pretty much anything, I'll be waiting a mighty long time.

But, I will head out to find a larger forest.

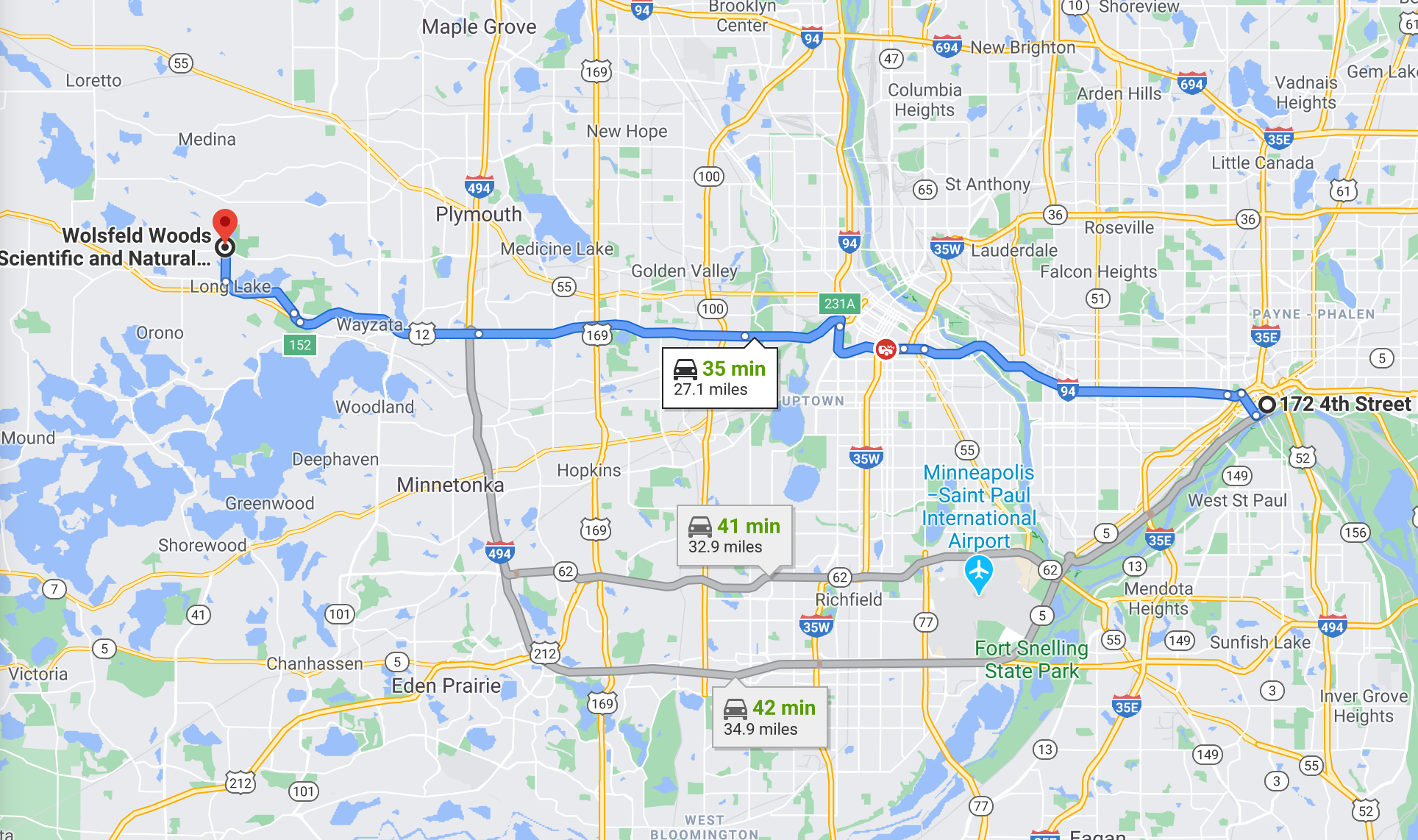

AN OLD-GROWTH FOREST JUST MILES OUTSIDE OF MINNEAPOLIS

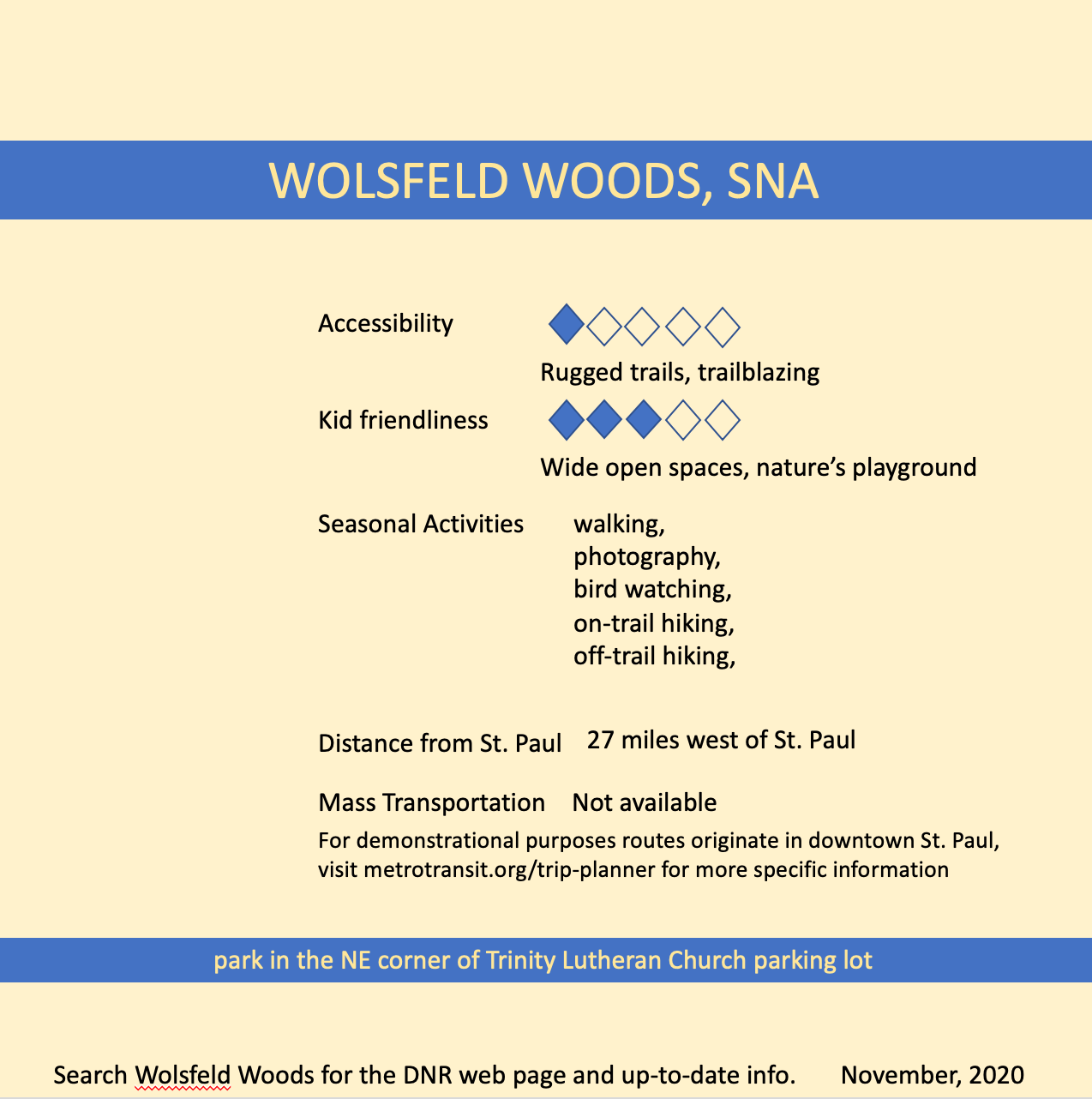

Wolsfeld Woods Science and Natural Area (SNA) is a 220-acre old-growth forest situated just 30 minutes by car west of Saint Paul in the town of Orono. There are a limited number of old-growth forests in Minnesota, in part because the land in many areas was fertile enough for European immigrants to begin farming as soon as they laid claim to their plot. The topography of Wolsfeld Woods is just hilly enough to make it unsuitable for early Europeans to cut the threes, till the soil and plant crops. Instead they used the sugar maple stands to harvest syrup. It's noted that some of the maple trees in the forest are over 200 years old.

However old the trees are doesn't matter too much to me; I'm more impressed with the tree-to-people ratio. I saw two people while surrounded by thousands of trees.

Walking the trailhead into the Wolsfeld Woods was akin to walking through a nave in a large cathedral. The path was narrow under a canopy of trees overhead, but soon the trail opened up to an endless series of small hills, gullies and trees. With no discernible path, I was presented with a choose-your-own-adventure type of walk. The act of looking for a way through the thicket allowed me no choice but to slow down and feel like I was a part of Wolsfeld Woods.

TAKING THE TIME TO BE WHILE BEING OUTSIDE

Taking time to commune with nature is empowering. I felt good as I sat and looked out through the trees. I didn't see much. Aside from two others at Wolsfeld Woods and three others at Reservoir Woods, I only saw one bird - a woodpecker. This is fine. I wasn't setting out to find birds. Aside from not dropping a camera or forgetting a tripod in the snow, I didn't have any goals in mind, except to be outside and away from people while giving my wary eyes something new - something distant - to focus on.

Honestly, forest bathing, or if you prefer the less-bougie 'taking a slow walk in the woods,' is a fantastic way to take care of yourself.

Find a new space, or revisit an old favorite. See it from a different perspective. Bring a chair. Why not a thermos of coffee? If it's public land, it's your land to use responsibly. Go out, have a slow-paced adventure and, when you get home, tell a friend. There are a lot of things we can do to keep ourselves healthy in mind, body and spirit during what promises to be the darkest winter of our lives.

8 TIPS TO SUCCESSFULLY BATHE IN A FOREST

1) Leave the electronics at home, or at least turn off your notifications. No dings. No buzzes. No distractions.

2) Find some outdoor space. Don't worry if your woods doesn't look like the rainforests of Oregon or have towering Redwoods of California - just find some trees. Any trees will do.

3) Walk slowly. If it's a paved trail, that's fine. If you're comfortable going off-trail, that's fine, too. You're not in a race. Calm yourself, be slow.

4) Breathe it all in. Be over the top about it. Breathe deeply.

5) Focus on your surroundings. What do your footsteps feel like? What does the bark of a tree feel like? What does the light feel like?

6) Dress accordingly, and bring a snack and some water.

7) Do not set a time limit Be out as long as you'd like to - this isn't an endurance challenge.

8) And finally: Yes, I'm a large man, and I've never had to worry about being secluded in the woods. If being alone in the woods doesn't seem like a good idea for you, consider forest bathing with friends. Stay within eyesight of each other, but have your own experiences. Move freely and at your own pace. Keep conversation to a minimum.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.

On a pristine day in October, Twin Cities Producer Luke Heikkila wandered down to Fort Snelling State Park for a few hours of skipping rocks across the Mississippi River. Both the rocks – and the time – flew by. He recounts his experience in this personal essay.

Twin Cities Producer Luke Heikkila also took in the rare experience of witnessing the October 2020 drawdown of the Mississippi River, a sight that got his imagination turning.

Let’s keep rolling, shall we? Luke Heikkila is no stranger to taking in the sights of Minnesota’s famous waterways. In recent history, he ventured north to take in the experience of an angry Lake Superior swept up in a powerful gale that blew in 86-mile-an-hour gusts and sent waves upwards of 20 feet. He even captured video of the occasion.