A Vietnam War Diary Brings a Fallen Soldier and Father Back to Life

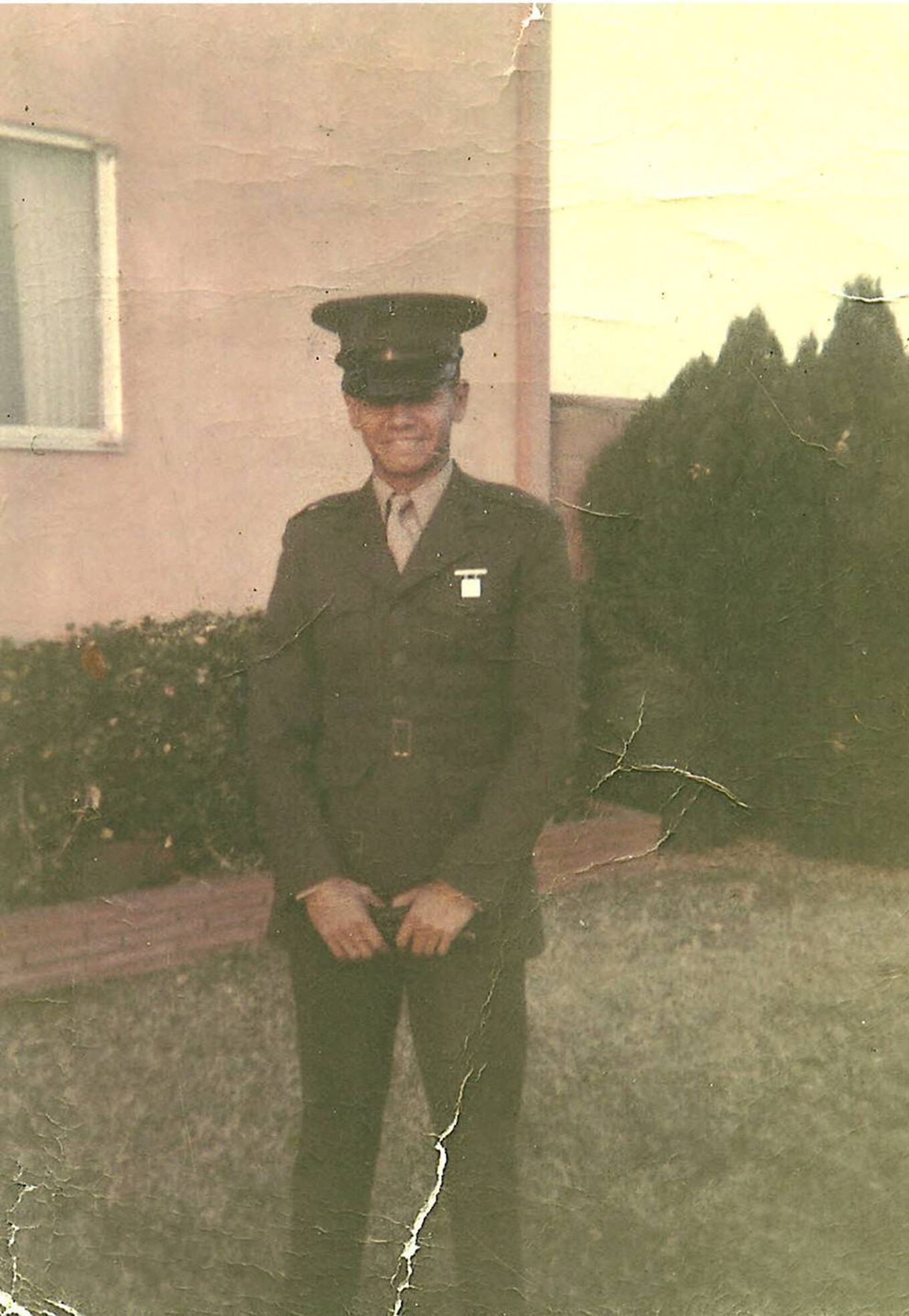

Sitting at my desk one Thursday afternoon, I was knocked off balance when the Billy Joel song "Goodnight Saigon" suddenly came on the podcast I was listening to. If you've ever heard the song, you know those lyrics are harsh: "We came in spastic, like tameless horses. We left in plastic, like numbered corpses." To be completely honest, it never takes much to start my tears flowing. A news story of a deployed serviceman returning to surprise his daughter at school. The actor Raymond Cruz getting shot on an episode of The Closer, because I imagine that's who my father would have grown to resemble as he aged. Hearing "Taps" on Memorial Day, Veterans Day, any day. But I'm okay with all of that because I've lived 52 years without having my father, Cpl. Thomas Soliz, USMC, to dry those, or any, tears.

I was 3 months old when my father was killed in Vietnam, saving the lives of those in his platoon who would go on to be police officers and doctors, fathers and grandfathers. Men who would go on to dry many tears, mine included. I have been told, once while standing alone at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C., that, by dying in Vietnam, he was spared the difficulties facing vets returning from 'that war.' Perhaps he was. But it's an existential question that I'll never have an answer to because I'll never know the man he would become, or at least I thought I wouldn't.

Until I was gifted something so miraculous, that is; something so extraordinary that it's hard to put into words. On Sunday, May 27, 2012, I traveled to Kansas City, Mo., to retrieve the diary my father kept in Vietnam, a diary that travel 8,473 miles to sit on a stranger's bookshelf for nearly five decades. In a small café on that warm Sunday in May, I heard my father's voice for the very first time. And the tears flowed with abandon.

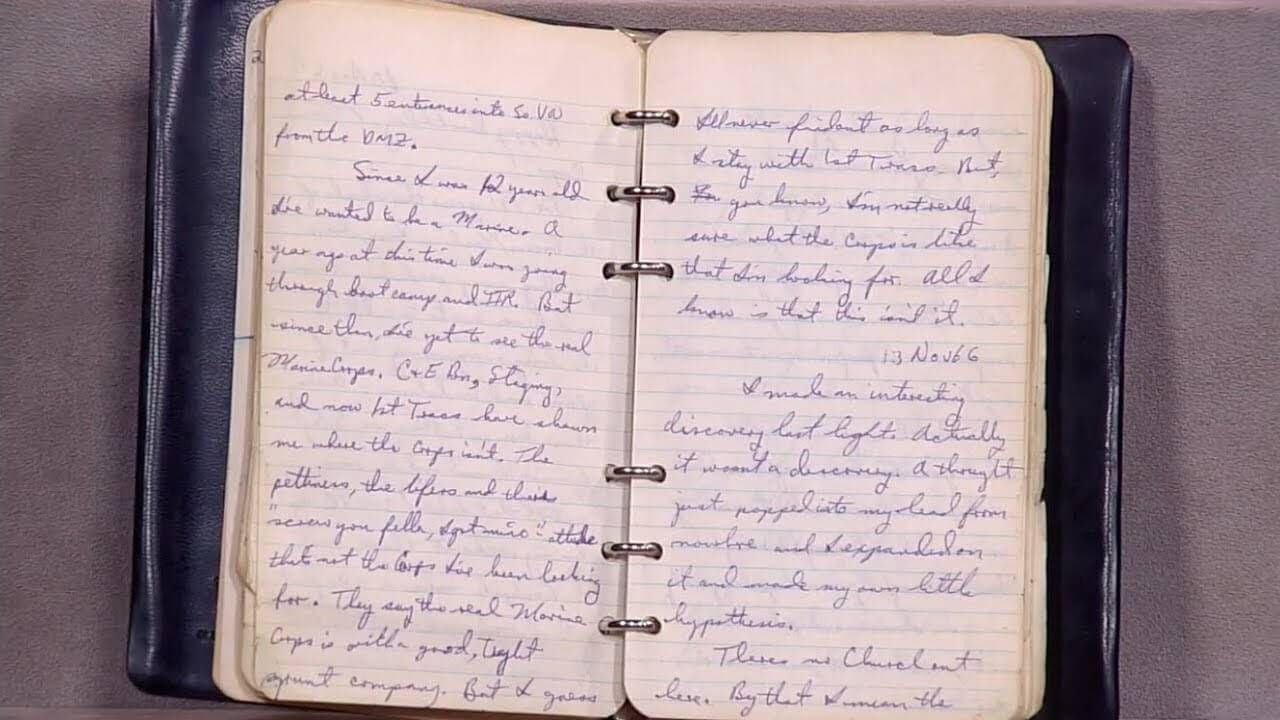

The diary is a small, black, three-ring notebook filled with insight and pain and loneliness. To give context to who Cpl. Thomas Soliz was, the entry from November 24, 1966 pretty much sums him up: "I'm nineteen years old today. Looking back, I don't see too much of any great importance that I can be remembered for. I've always considered myself emotionally more mature than others my age. I was 18 when I got married; 17 when I enlisted. And here I am, 19 years old, a corporal and a radio tech in the Marine Corp service in Viet Nam. I can't believe how incredibly lonely I am."

A look at a 1966 calendar shows that November 24th was Thanksgiving. This would not have been his first birthday or Thanksgiving away from home, but Vietnam was much farther from Bakersfield, Calif., than San Diego was. And in 1965, he had his girlfriend – his soon-to-be wife - to spend the day with. I can only assume that the loneliness from that day, from being away from my mother, and his mother, led to a very drunken, expletive-filled entry the next day that closed with "…facing the Viet Cong is nothing compared to the hell of being lonely. All the VC can do is kill you, but the loneliness can drive you insane."

At times, loneliness is replaced by disillusion, both in his corps and in the war. "I'm slowly learning what I came here to learn," he writes. "I know what it's like to be cold, and hungry, sleep on a hard deck, be so filthy I can hardly stand the smell of myself. And I'm learning the price I'm paying with the promises to God I've made. I'm paying it with boredom, as well as pain, disillusionment, as well as discomfort. But mostly disillusionment. I said in the first entry that no effort in Viet Nam was wasted. God, how wrong I was! There is so much petty crap and wasted energy and talent, I can hardly believe it."

Later he considers the journey to that place of disillusion: "I wonder if I could go back seven years to when I was twelve, when I was all gung ho to the Marine Corps and to military life in general, when I was all for the spit-and-polish, the shine, and the precision and glory. I wonder what my reaction would be if I was twelve and I saw the way I would be at nineteen, in Vietnam, with 14 ½ months in the Corps. I don't think I'd believe what I saw. I'm sure when I was twelve, even when I was in boot camp, I didn't expect so much disillusionment and disappointment."

Nearly every entry is also peppered with some measure of self-reflection, but none more the entry on April 19, 1967: "What I didn't have the guts to say was that I'm just a kid. I don't have enough maturity to face my responsibilities directly. True, I've taken out five patrols and am going out tonight; 5 times I've been in control of several men's lives. Taking patrols out is not my main job. I'm a radio tech, not a grunt. Is accepting the responsibility of men's lives more important than facing up to one's designated responsibilities? Or do they both go hand in hand? Am I a full man or just half a man? Or am I still a kid. God, please give me the strength to find out within the next six months."

There are times as I read these entries that I am struck hard by the fact that this writer, this kid, is my dad. The intelligence, the introspection, the raw emotion that comes through each entry leaves me feeling sad and proud, but mostly blessed that, although I don't have him, I have his thoughts.

Perhaps my favorite demonstration of everything he was in Vietnam comes through in the entry on April 20, 1967. It is a single running paragraph of insight that belies his age: "I walk through the cool breeze, feeling the night around me, welcoming its anonymity. I am pelted by the night's noises. The sounds with which nature identifies the night. I hear and I feel, I do not see. Occasionally the noises of humankind shatter the night, the noise man identifies War with. The roaring crescendo of a jet engine. The thunderclap of an artillery piece, the staccato of a machine gun, or the single crack of a rifle. Through the night and the noises, I walk alone, carrying about me an envelope of loneliness from which the only escape is an active mind. Among 427,000 men, I am alone in Viet Nam. I have been alone now for 6 ½ months and will remain alone that much longer. What is Viet Nam? To some it's rice paddies and heat, to some it's mines and snipers, to some it's booby traps and hidden VC. To me, it's loneliness."

The last entry on August 27, 1967 harkens back to the one on April 19, 1967, and speaks more to the fear he felt as an individual, as a guy who just wanted to go home to kiss his wife and hold his baby daughter. "I'm scared. Dear God, how I'm scared. We go north again tomorrow. I've had so many close calls and not one scratch. When will my luck run out? How many more bloody Marines will I see? How many more people will go insane? How many more of us will die? When will people realize that the shattering of a body or a mind in such a horrible and senseless thing as a war is the greatest sin against the most beautiful creation in the universe, a human being? I've seen too much blood, too many dead, and too many irreparably twisted and shattered minds. I expect no answers to my questions because a blind man cannot describe beauty, and an idiot cannot discern right or wrong. I can only await the inevitable and ask: when will it be me?"

And then it was him. On September 6, 1967. Without thought of personal safety or survival, he acted with "extraordinary heroism…climbing aboard an amphibian tractor to man a machine gun…he proceeded to place a heavy volume of well-aimed fire on the enemy, which enabled the platoon to gain fire superiority, deploy to better defensive positions and evacuate several seriously wounded Marines. As he was delivering this devastating fire into the enemy, he was severely wounded by enemy fire which rendered him unconscious. Before assistance could arrive, Corporal Soliz was hit again and mortally wounded." This text is from the citation for the Navy Cross, given to him for his actions on that day. And it is perhaps the last sentence that takes everything he wrote and punctuates it with more sadness: "Corporal Soliz's concern for the other members of his platoon, coupled with his keen professional skill and unfaltering dedication to duty, were in keeping with the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country."

In the end, when it mattered most, he set aside everything he thought he was and became exactly what he was meant to be: a hero. And I am so proud.

This story is part of the collection The Call to Serve: Stories of Sacrifice, War and the Way Home, which was funded by the Fred C. and Katherine B. Andersen Foundation.