A Short History of African Americans at the Minnesota State Fair

For a number of years there have been protests by Black Lives Matter activists at the Minnesota State Fair. Protestors have used the State Fair as a backdrop to air concerns about the criminal justice system. They have also raised questions about the Minnesota State Fair's commitment to diversity in terms of fair vendors and activities. The debate is not new.

Diner Tradition

It turns out that African Americans have had a presence at our State Fair for well over a century. A small note in the Western Appeal newspaper in 1887 proclaimed the presence of a fair food tent sponsored by the St. James A.M.E. church. St. James was our state's first black church having been founded in Minneapolis during the Civil War. The state fair church diner tradition apparently goes back a long way. The State Fair of 1889 featured an "Emancipation Day." One of the speakers that day was Minneapolis' first African-American attorney William R. Morris who had arrived in town just months earlier.

Fair Awards

It may surprise many that state fair ribbons of color were awarded to Minnesotans of color in the 19th century. Newspaper accounts show that at the fair of 1890 a black painter by the name of John R. White was awarded a blue ribbon. And in 1891 pioneering St. Paul African-American photographer Harry Shepherd won the first of two state fair blue ribbons for his photo work. For years afterwards Shepherd proudly displayed his Minnesota State Fair ribbon in all of his advertising.

History of Discrimination

Unfortunately a good portion of the history of African Americans at the Minnesota State Fair involves struggle with being treated fairly within the fairground gates. Starting about the time of the First World War, the local black press is filled with accounts of state fair bias. For example, in September of 1913 Mrs. James Darby was racially insulted in the Midway by a vendor from Georgia. What the vendor probably didn’t know is that Minnesota had a statewide civil rights law since the 19 century. The Georgia vendor was fined five dollars for his racist act. While that doesn't seem like a lot of money, it would be the equivalent of a $125 dollar fine today.

In the autumn of 1914 the Twin City Star newspaper ran an editorial saying that if any of its readers faced discrimination at the fair that they were to report it to fair officials. The newspaper goes on to write: "The State Fair Board will tolerate no discrimination by prejudiced concessionaires. Remember this is Minnesota."

Fair Vendors

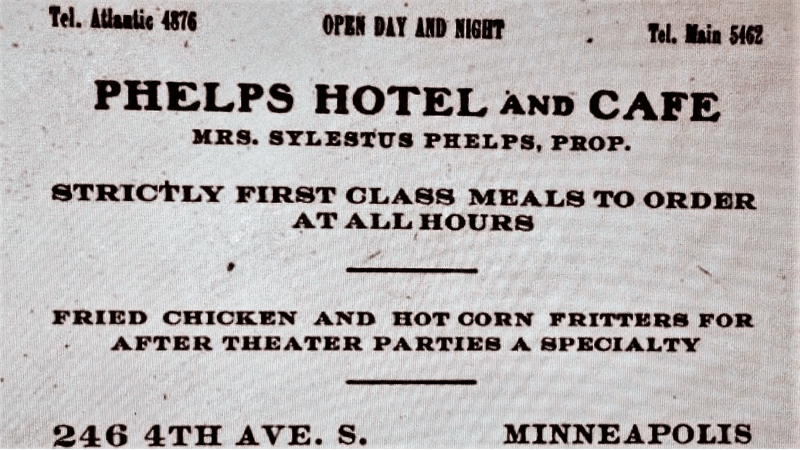

At the same time that fair racism increased there was a growing presence of black-operated lunch counters and concessionaires at the fair. The pioneer here was restaurateur Sylestus Phelps of Minneapolis. Her "Oh Boy Chicken Shack" first surfaced on the fairgrounds in 1919. But Phelps soon had competition. In 1922 fellow African American Floyd McKensie established his "Old Kentucky Kitchen Chicken" counter. A decade later F. B. Sheldon operated the Dixieland Plantation Barbecue across from the Hippodrome.

But the Great Depression wasn't kind to black fair vendors. By 1938 Phelps was the only black concessionaire at the fair. And something besides bad economics was at play. The Minneapolis Spokesman noted that signs proclaiming "Colored trade not solicited" were popping up around the fairgrounds and that blacks were being denied admittance to some Midway shows.

In 1940 Reverend C. F. Stewart was told his five cent state fair soda would cost him one buck and twenty five cents. The vendor picked on the wrong guy. Reverend Stewart just so happened to be the president of the Minneapolis branch of the NAACP. Stewart and pioneering African-American attorney Lena Smith and Minneapolis Spokesman newspaper editor Cecil Newman worked together to fight state fair racism. Their efforts paid off. In a September 1941 edition of the Spokesman Newman proudly editorialized that there were no bias problems at the fair that year.

"Out of the Shadow"

Further change was coming. In 1943 Cecil Newman suggested to Minnesota's new governor --Republican Ed Thye-- that a statewide inter-racial commission was needed. Thye was up to the challenge and formed the group. In 1944 the newly appointed governor's commission created an exhibit on racial tolerance and set it up at the State Fair.

In 1948 Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey –a friend and ally of Cecil Newman-- made waves nationally with an electrifying speech at the Democratic National Convention challenging his party to "get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights."

Later that summer the Governor’s Inter-racial Commission again took its message of tolerance to the fair. The Minneapolis Tribune published a photo of a billboard that made an appearance at the fair that year. The billboard depicted an interracial group of children. The young children look out from the billboard and ask the reader: "Prejudice in our Town. What's That?" The slogan on the bottom of the billboard said simply "Keep our Children Free from Racial and Religious Hate."

And more than a half-century later that is still the challenge facing all of us.

Brendan Henehan is passionate about Minnesota history. He has compiled an index of more than a dozen historic African American newspapers in Minnesota and he's never happier than when the index is used to uncover lost history.

This story is made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund and the citizens of Minnesota.