A Movement or a Moment? A Look at Political Activism After George Floyd.

John Thompson remembers the day his friend was shot and killed by police like it was yesterday. On July 7, 2016, Thompson started the day by turning on the news. He didn’t realize what happened the day before until the name “Philando Castile” commanded the bottom of his screen.

“I woke up everybody in the house, ‘They killed Phil!’” Thompson remembers telling family. “I couldn’t even go into work that day. As a matter of fact, they called me and said I could come in and speak to the crisis counselor. But I just stayed home.”

Castile’s death sparked protests in Minnesota and calls for justice across the nation. It also motivated people to take political action to ensure laws would prevent another unnecessary death while interacting with police.

A comparable surge of minority voices has responded to the police killing of George Floyd. In the weeks since Floyd uttered, "I can't breathe," as ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pressed down on his neck, a new collective of individuals is taking action by running for office, engaging in politics and stirring change among youth - and Thompson is among them. The momentum is part of a historical cycle that is unsustainable, but could lay the groundwork for substantive change.

A Promise

The day before Castile died, Thompson and his friend agreed that nothing would happen to officers who killed Alton Sterling, who was fatally shot by police in July 2016 while he was selling CDs outside of a Baton Rouge, La., market. Thompson was a machinist, doing contract work for schools across Minnesota. In that time, he learned a lot about Castile, a school cafeteria supervisor. He discovered that Castile liked to play video games, enjoyed chess and once took money from his pocket to help a student pay for lunch - an act that could have gotten Castile fired.

But Thompson remembers news media painting Castile in a different light, highlighting the smell of marijuana that the officer who shot him, Jeronimo Yanez, said he smelled in the car, as well as speculation around a robber Castile was said to look like. Media coverage of the police who killed Floyd remind Thompson of that time, and of a promise he made soon after.

“I promised my mother and my friend that I would make them proud of the work that I’ve done,” Thompson said. “And I’ve never been more passionate about any work I’ve done in my life.”

As a first-time candidate for state representative this year, Thompson lists Castille’s death as a primary motivator to pursue political office. And Thomspon has similar company. Dozens of Black women are running for office this year, and groups like Black Lives Matter and the University of Minnesota's Black Student Action Committee have mobilized in response to George Floyd’s death in order to stir political change.

A Movement, Or a Moment?

Alberder Gillespie has involved herself in politics for nearly 20 years, but she said this year is different. Gillespie helped create the Black Women Rising movement and is running to represent Minnesota in the U.S. Congress, and she says the pandemic has exposed pre-existing disparities.

“We all saw Philando Castile get murdered four years ago. That’s not new. People dying from chokeholds in police custody isn’t new, but these were not priority issues,” Gillespie said. “Philando Castile turned out [to be] a moment. Trayvon Martin - a moment. We have had many moments, but we do need a movement.”

Gillespie said people must elect legislators and officials who will prioritize such matters. But that may be easier said than done.

Michael Minta, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota, studies how minority representation affects policy. Minta said there have been moments of increased political activism similar to this, and the death of George Floyd has moved people into action - but that does not mean people will support solutions to these issues.

Minta said combining grass-roots activism with politics would spur real change, but activists need the money and motivation to be relentless with their work.

“A lot of protesters and a lot of grassroots organizations, they have limited resources and funds to really keep this sustained effort going,” Minta said. “Those types of groups that get change, they just keep coming back. They keep running candidates, they keep the pressure on, they give money, they make donations, until policy eventually changes.”

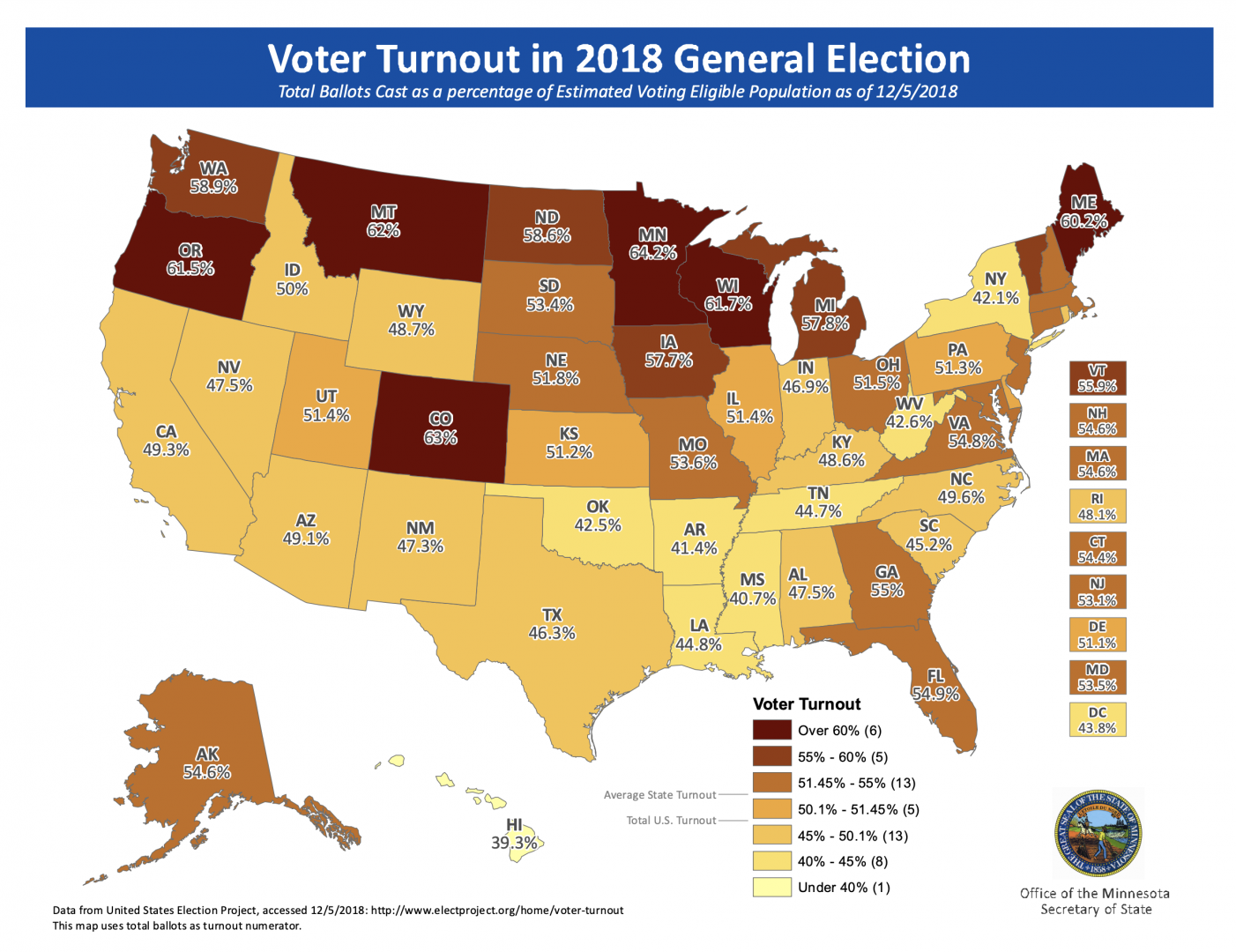

You also need a politically engaged audience, but Minnesota outranks many other states on that front. A survey by WalletHub, a website that offers financial advice, found that Minnesota ranked first in the nation for political engagement among African Americans. The Secretary of State’s office does not collect data of registered voters’ race, but a map shows that Minnesota reported the highest voter turnout percentage in the nation for the 2018 general election.

Even when a new politician lands in office, though, work to promote change in Minnesota can be difficult.

“A Disconnect”

As executive director of the Council for Minnesotans of African Heritage (CMAH), Justin Terrell brings personal experience with racial disparity to the table. Terrell grew up in South Minneapolis, experiencing homelssness with his family and working from the age of seven. Those experiences motivated him to serve the community and to advise legislators on needs among people of African heritage in Minnesota.

Terrell noted that this is not the first uprising the nation has witnessed. There were similar calls for change after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and after the acquittal of the police officers who were filmed beating Rodney King during a traffic stop. But Terrell said Minnesota is unique in that the state’s racial disparities have been caused by policy makers’ decisions. He said Minnesota must build a greater understanding of others as it moves forward.

“The fact the city has to burn in order for lawmakers to really take swift action tells you how far we really have to go. There’s a disconnect,” Terrell said. “These issues are not ‘Black people issues’ in the state … we’re all in this boat together. And we’re going to sink or we’re going to keep it afloat and do something that the nation needs us to do.”

Terrell said that activists drive many issues that policy makers look into, and the state needs more Black leadership. After two years at the helm of CMAH, his last day in that leadership role will be August 21, opening up an opportunity for someone else to impact change.

He declined to share what nonprofit he will work at next, but Terrell plans to continue serving the community while opening up his outgoing role to a new young leader.

A Future

In step with Terrell, John Thompson also wants to motivate youth, like his own children, to step into those kinds of roles.

Thompson never imagined running for office. He worked as a machinist for 11 years, and did not engage in politics then. Now he is motivated by that promise to his mother and to Castile, as well as by his children. Thompson said his 11-year-old son is watching him move through the campaign trail; and his 15-year-old daughter marveled at his chance to speak with NAACP Minneapolis Vice President Anika Bowie, whom she sees as a celebrity.

Thompson said that youth must be shown that they can do this, too - and that this surge in political engagement is the new activism.

“If you’re a legislator, you ought to be shaking in your boots right now. Because those La-Z-Boy chairs that we furnished for you [with] our tax dollars, we’re coming for those seats. We’re coming for those offices,” Thompson said. “We don’t need another rapper, we don’t need another NBA superstar. We need some lawyers, we need some prosecutors, we need some legislators … and if we don’t raise them, then we don’t get them.”

Editor's notes: A previous version of the article incorrectly stated Alberder Gillespie is running for state Legislature. She is running for U.S. Congress.

After the August 11th Primary, Alberder Gillespie did not make it to the November ballot, but John Thompson did. On August 15th, Thompson's name was in the headlines after he made some explicit comments about the city of Hugo at a demonstration in front of Minneapolis Police Union Chief Bob Kroll’s home. Thompson has since apologized.

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

Thousands of other Minnesotans are struggling with the possibility of being evicted later this year due to COVID-19-triggered economic issues. Many of those in danger of eviction are among the state’s more vulnerable individuals, and they could be homeless before 2020 comes to a close. Almanac data reporter Kyeland Jackson takes a close look at the toll a pandemic is having on residents, landlords and advocates, alike.

George Floyd’s police killing has inspired countless artists across the globe to create murals in his honor, works that also call for justice and anti-racism reform. And that’s left a lot of people wondering what will happen to the works of art – many created on temporary surfaces such as plywood panels – when communities start to rebuild. Students and professors at the University of Minnesota have created an online database that aims to catalog these expressions so they can be studied for years to come.

Saint Paul’s neighborhoods of color have a disproportionate number of vacant buildings than areas primarily occupied by white residents. That fact has a direct impact on crime rates, public-health risks and quality of life. Data reporter Kyeland Jackson examines the links between vacant properties and the city’s racial disparities.