A Black Mother Contemplates What It Means to Defund the Police

...and for the future she envisions for her son.

I remember once, many years ago, watching a boyfriend run down a dimly lit street in downtown Minneapolis, a small package under his arm for the FedEx office on the next block. I sat in the car watching and waiting for him, unprepared for the sudden rigidity of my spine, the hole in my stomach. My eyes peered anxiously at the passersby he raced past, waiting for someone - a white woman in a suit and heels, a cop coming out of the corner store - to grab him or knock him down suddenly, unhinged by the spectacle of his freely moving body.

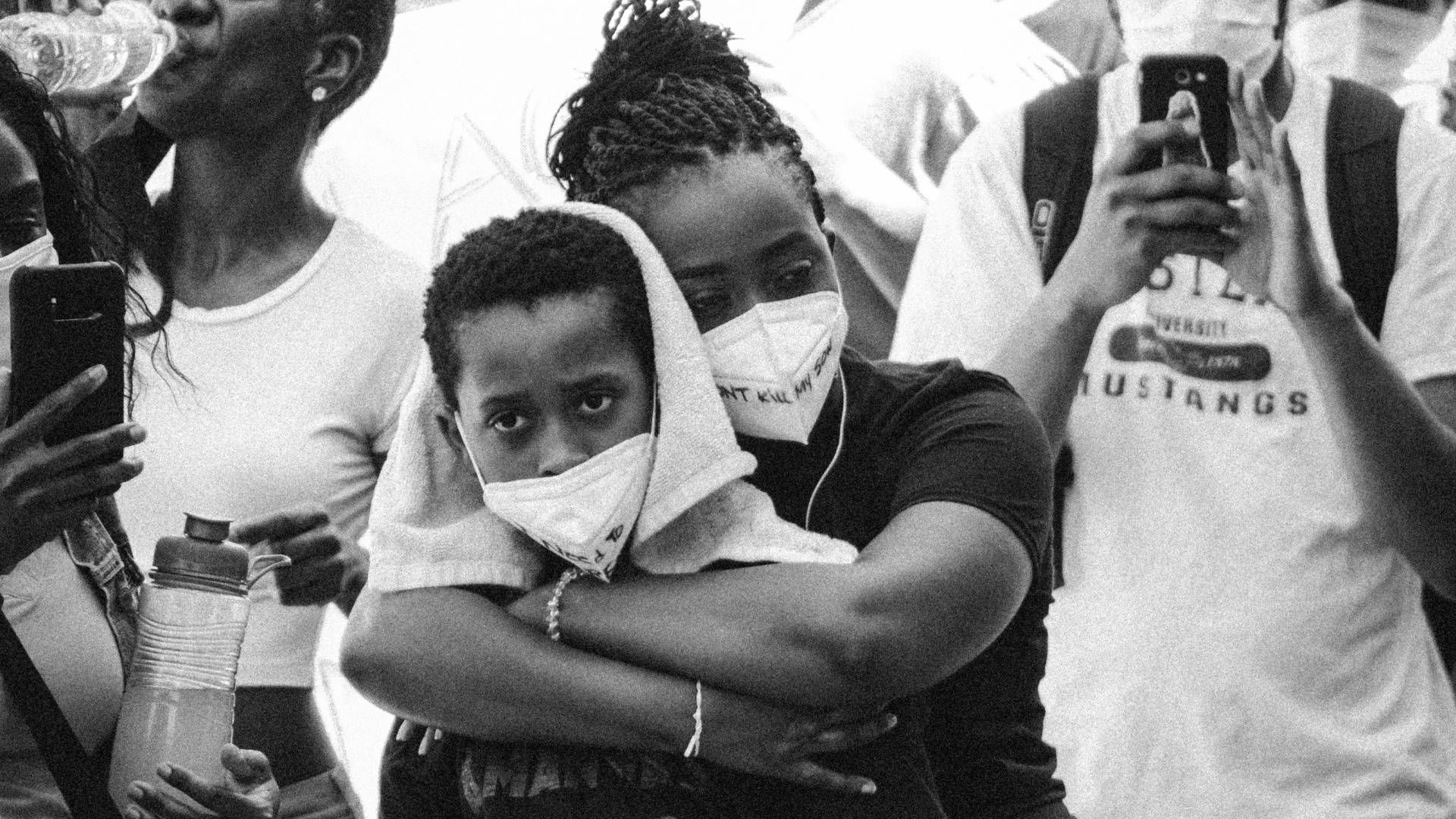

I hadn’t known until that exact moment what it meant to love a body that the politic built a nation around controlling and, in fact, destroying. These days, loving my Black tween son, I have a new and constant intimacy with the experience.

As we settle into the era of post-George Floyd, post-protest, hundreds of institutional commitments to “anti-racist” initiatives, defunding the police movements and their inevitable backlash, rising crime rates, and incremental policy change to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD), I look at my son, an affectionate, funny, caring, deeply engaged 10 year old, and I wonder what his choices will be to push toward change.

Of course, I also wonder about the costs.

Boisey wants to be involved; I have raised him that way and that is who he is anyway. But as an adult, a student of history and a Black citizen myself, I know all too well how white people and white institutions so often plant the burden of social change on the backs of the most vulnerable. You push for the change that everyone says must happen, that everyone says they want, and in doing so, you become “The Problem” in the organization, the school, the community. Having been “The Problem” my whole life, I want more for Boisey. And yet, I know that nothing changes unless people change it. And the people who usually have to make it happen are those who are most at risk from the system. It’s a conundrum I haven’t worked out in my mind or heart. No Black parent has.

And yet, here we are.

The Minneapolis City Council recently voted to cut the MPD budget for the first time in 20 years. This $8 million will fund a new mobile mental health team, community-based violence prevention programs, and move property damage and parking calls into other City departments. But it was a battle, even for these small victories. The number of police officers was not cut, despite pressure, and the establishment mayor threatened to veto the whole budget. The MPD still has a $171 total budget, and little-to-no accountability measures in place.

This is the pace of institutional change in a city that is still majority white - liberal, but not liberal enough to alter the racial power dynamics in any significant way. This is the culture of a place with some of the worst racial disparities in income, homeownership and housing access, incarceration, employment, education, and health care in the nation.

This is, for all intents and purposes, the place I have chosen to call home. It is the place I am raising my family. The place whose opportunities and contradictions I struggle with every day. And as my son grows more and more into the Black man he is destined to become, he will, too.

The thing that depresses me about this inevitably long fight is not even the exhaustingly slow pace of bureaucratic change, but the distance between the racial reality of some of my white friends and neighbors, and mine. Though they may only say it privately to other white folks and City employees as they contemplate an increase in shootings, car-jackings, drug use and petty crime in our neighborhoods during a pandemic, many of them really do feel safer in their bodies with more police, continued police funding, and little accountability. This is something so far away from my daily lived experience in my own body, and caretaking my son’s, that it is almost unfathomable. The durability of racist practices within institutions, even and especially those that identify as “anti-racist” is depressing, as well.

What is hopeful, though, is that the term “defunding the police” is now firmly ensconced in the American lexicon - something I could not have dreamed of even a year ago. Many people don’t agree with the concept of defunding the police, but they nevertheless have to consider it as a possible strategy to ending police violence in the wider public discourse. We can’t bring anything into being that we can’t imagine, and we can’t deeply imagine what we can’t articulate. Words matter.

What gives me the most hope, however, is my son. We live about 13 blocks from where George Floyd was killed, and when I suggested that he and his sister and I go down to the memorial at 38th and Chicago this summer to pay our respects and be with the people, he was initially reluctant. And I understood: Why would you want to go to the spot where a man was killed in cold blood? But we went, and he marveled at the murals and artwork of all kinds on the streets and buildings, approached two men drumming to discover how they were doing it, kibitzed with some kids in the street.

“Nothing will happen to those cops who killed him,” Boisey told me after he learned of the murder. My first thought was that I was raising him right. My second thought was that I have to keep on showing and exploring all the various ways of fighting.

And that sometimes, loving and fighting are the same thing.

Shannon Gibney authored the essay “Fear of a Black Mother,” which begins the best-selling anthology A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2016; Sun Yung Shin, ed.). She is a writer, educator, activist, and the author of See No Color (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), and Dream Country (Dutton, 2018) young adult novels that won Minnesota Book Awards in 2016 and 2019. Gibney is faculty in English at Minneapolis College, where she teaches writing. A Bush Artist and McKnight Writing Fellow, her new novel, Botched, explores themes of transracial adoption through speculative memoir (Dutton, 2022).

This story is part of the digital storytelling project Racism Unveiled, which is funded by a grant from the Otto Bremer Trust.

Along with other urban centers across the country, the Twin Cities have a history of racially discriminatory housing covenants that prevented people of color from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. That history ripples in the present-day affordable housing crisis: By limiting opportunities for home ownership, people of color were stripped of one key way to build equity over time. Discover more in “Mapping the Roots of Housing Disparities in Minneapolis.”

A surge of minority voices has responded to the police killing of George Floyd. In the weeks since Floyd uttered, “I can’t breathe,” as ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin pressed down on his neck, a new collective of individuals is taking action by running for office, engaging in politics and stirring change among youth. But is the momentum a movement or a moment?

Vanessa B. Agnes could not stand idly by as the city of Minneapolis grieved George Floyd’s police killing. So, in a 10-day period of time, she curated “the Uprising Vol. I.” This June 2020 event brought immense healing to the hundreds of Twin Cities residents, who gathered in a church parking lot to experience stories, spoken word poetry, dance, and song. Now, her new performing arts collective, Dark Muse Performing Arts, is flourishing and spreading hope throughout the Twin Cities.