6 Facts About Saint Paul's Historic Ford Plant

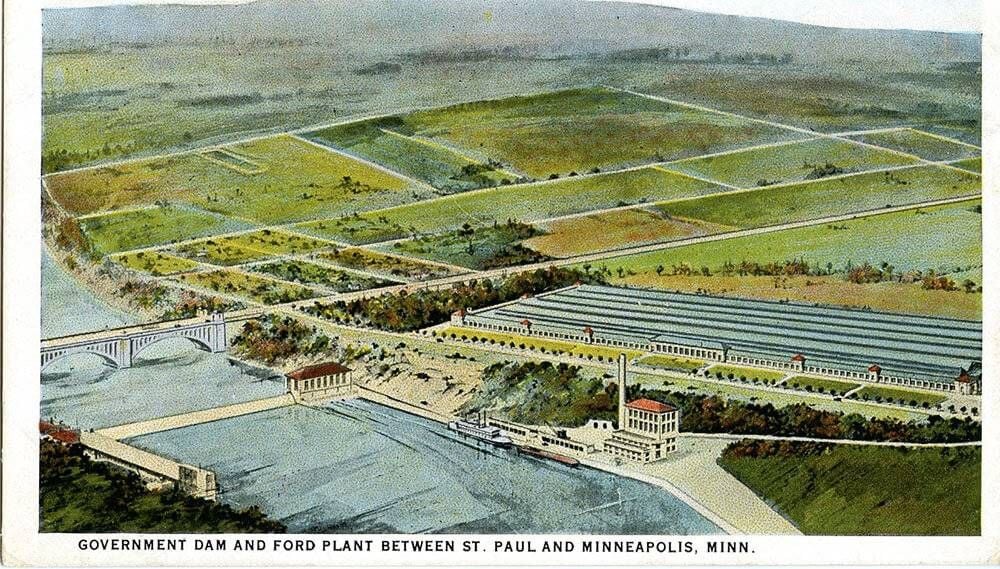

Pioneer of American car manufacturing. Inventor of the assembly line. One of the world's first "green industrialists." While Henry Ford may not have invented the automobile - that credit usually goes to Germany's Karl Benz for his 1886 "Motorwagen" - he did put the United States on the global car manufacturing map. Completed in 1925, Ford's Twin Cities Assembly Plant high on the banks of the Mississippi River in Saint Paul was a sterling achievement.

But it wasn't the first Ford facility built in the Twin Towns. In 1914, the Ford Centre opened in Minneapolis, the largest car manufacturing plant in the world at the time. But the facility, which still stands at 420 N. 5th Street, was short-lived. While construction unfolded, Ford was already experimenting with assembly line prototyping, and his system was perfected before the Minneapolis plant started making Model Ts - a system that allowed cars to be assembled in a record 93 minutes, rather than twelve-and-a-half hours.

By about 1920, Ford already needed sprawling acreage to accommodate the assembly line, room for growth and construction, and ample parking space. So the Saint Paul facility sprung into being after two years of construction. Today, the former buildings of the Twin Cities Assembly Plant have been bulldozed into rubble, leaving behind a desert of dirt, weeds and chainlink. Many people who call the Twin Cities home, only familiar with the debates about what to do with the empty site, may not know much about Ford's topsy-turvy history in Minnesota.

So without further adieu, here's a small glance at 6 details about the plant - and about Henry Ford - that may surprise you:

The plant was also a glass mine.

The concept of harnessing the power - and the cost savings - of raw materials was critical to Ford's vision of a modern manufacturing facility. To take advantage of the rich amount of silica sand on the site, tunnels and a mine were constructed directly below the plant. Shoveled into a glass furnace, the sand became the windows installed in Model Ts and other models of Ford cars.

The Mississippi powered the plant.

Some people marvel at the Mississippi for its collection of bald eagles and its billion-year geological history. But Henry Ford saw a cheap source of power. Built on the site of one of the river's oldest dams, the Twin Cities Assembly Plant required a more robust dam in order to produce enough hydropower for the operation - and a more powerful version was completed in 1932. Now operated by Brookfield Renewable Power, the reconstructed dam generates enough energy to power 14,400 homes for a year.

Henry Ford had some opinions.

And many of those opinions would make many of us cringe today. During Ford's childhood, the numbers of Jewish men, women and children immigrating to America from Europe reached an all-time high - which led to a wildfire of anti-semitism. Throughout his life, Ford wrote and published a battery of anti-semitic articles in The Dearborn Independent, the hometown newspaper he later purchased: "Ford published articles that would refer to Jews in every possible context as at the root of America and the world's ills. Strikes: It was the Jews. Any kind of financial scandal? The Jews. Agricultural depression? The Jews. So 'the Jew,' in a way, became the symbol of a world that was being manipulated and controlled." For more on Ford's anti-semitism, check out this piece from American Experience.

The Ford plant followed history.

American families and business, alike, faced devastating losses after the stock market crash of 1929. The Twin Cities Assembly Plant was no exception. With far less demand for vehicles, the facility closed for two years during the peak of the Great Depression. But as the U.S. entered World War II, many home-front industries shifted their manufacturing capabilities to make products aimed at supporting the war effort. Between 1942 and 1945, the Ford plant in Saint Paul heeded the call, making small armored cars and components for aircraft.

Who's the fairest plant of them all?

Well, this one, of course. Designed by celebrated architect Albert Kahn, with a lot of influence from Henry Ford, the plant was situated high above the mighty Mississippi, with ample green space surrounding it and classical-inspired buildings covered in red shingles. Naturally, the facility earned a reputation as "the most beautiful industrial plant in the world."

Ford struggles with the United Auto Workers.

In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt's allies in Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act - also known as a the Wagner Act - which gave workers collective bargaining rights and protected them from heavy-handed, unfair practices on the job. By 1937, both Chrysler and General Motors struck up deals with the United Auto Workers after strikes stalled production. After riots and bloodshed threatened to close his River Rouge plant - and after his wife threatened to leave him if he did not put an end to the violence - Ford, who despised unions, finally came to an agreement with UAW in 1941. But in an unexpected twist, he also agreed to match the highest wages in the industry and to deduct union dues from workers' salaries - an accord that beat the deals UAW struck with both Chrysler and GM.

Dive into the history of the Twin Cities Assembly Plant and explore the stories of the people who worked there in "Made in St. Paul: Stories from the Ford Plant" on Minnesota Experience.