100 Years After the Duluth lynching, Another Face Is Added to the 'Mob' of Systemic Racism

Twin Cities PBS Senior Producer Daniel Bergin offers a perspective on Minnesota's history of racism.

Editor's Note: The video and some photos in this article reveal some disturbing imagery that we believe is important to understanding the history of systemic racism in Minnesota.

Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie killed by a white mob in Duluth in 1920. George Floyd killed by Minneapolis police in 2020.

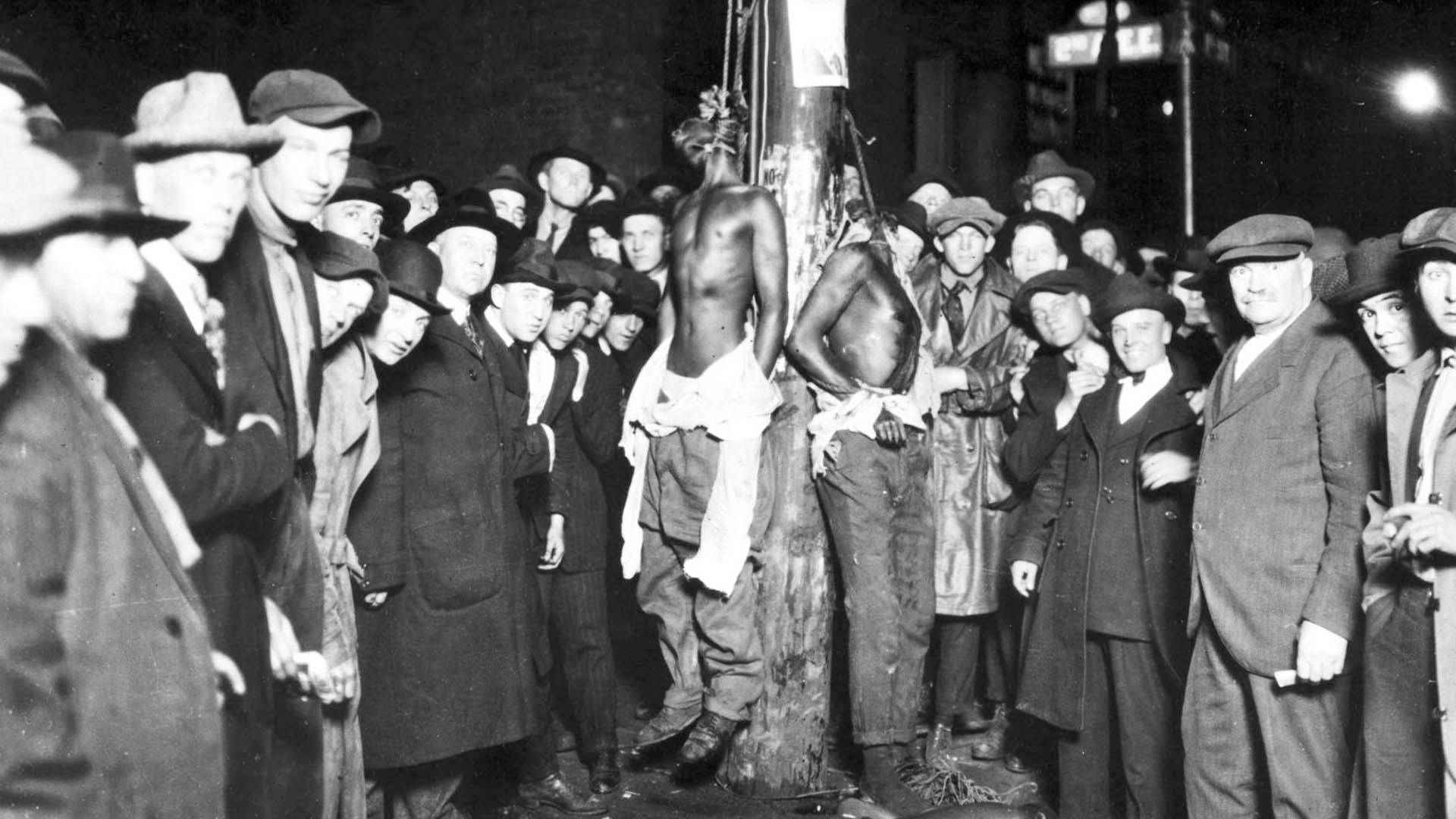

Views of both deadly scenes, taken 100 years apart, are hard to look at. But both must be seen. As we remember Clayton, Jackson and McGhie at the centennial of their terrible lynching on June 15, 1920, we are also mourning George Floyd’s police killing under the knee of systemic racism. We are experiencing - in literal, figurative and visceral ways - the presence of the past in present tense.

The images are interchangeable across the century that separates them. One was taken to make eternal a bloody tableau to affirm and extend the lethality of Willie Lynch and Jim Crow. The other, a video captured on a mobile phone by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier, was taken in a resolute attempt to counter that type of terror 100 years later.

The visual link across time is the face.

Eerily, Derek Chauvin’s face could easily be transposed to the mob of murderers from 100 years ago. Not because of racial features of a white man cheaply applied in a "they-all-look-alike" manner. That’s not fair or appropriate. It is, rather, his expression and cold countenance that could place him among the faces from 1920. The face of white supremacy unleashed. Not frothing at the mouth and contorted in fiery Dixie rage, but calm, emboldened by bias and brutal systemic racism that too often kills Black people with impunity.

Sadly, Officer Tou Thao’s face from Darnella’s video also fits into the menacing menagerie of faces from 1920. Some might defend his look as that of "professionalism" in the face of challenges from the increasingly panicked onlookers. But a more fitting description is that Thao’s gaze is one of detached, uncaring antagonism. An expression shaped in part by working in an institution where "warrior training" has been more welcome than diversity, equity and inclusion training.

So both images were developed in a fixing bath deeply rooted in race hegemony that’s as old as America. But the sharing of these two images, at opposite ends of a century, are also at opposite poles of purpose.

The distribution and impact of these two views present the existential struggle of our nation between justice and injustice, right and wrong. The lynching photo is a totem of the reign of terror in America, especially in the past. The Floyd video, it seems, might force a real reckoning with that past for a more just American future.

There were hundreds of confirmed lynchings in America from Reconstruction to World War II. There are many photos of these atrocities, each grislier than the next. James Allen’s Without Sanctuary (exhibit and book) was a landmark gathering of these images and stories that, for most of the 20 Century, occupied a hushed space in American history, culture and identity. Another important documentation of this shadow history is the book A Time of Terror, James Cameron’s account of surviving a lynching in Marion, Ind., that saw the "demonic" murder of his two compatriots. As the last of the three was dragged to his would-be doom, Cameron described the mob:

“The crowd cheered wildly, jumping up and down in an insane and intense excitement as Tommy feebly writhed at the end of the rope. For all of 20 minutes, they pushed and shoved among themselves to get a closer look at the ‘dead nigger.’ The spectacle whetted their murderous appetite. They began chanting for ‘another nigger.’ Many uniformed policemen of the Marion Police Department helped the mob to clear a path through the swarming thousands of people so they could get me all the way up to the tree where Tommy and Abe were hanging in shredded clothing.”

Miraculously, Cameron, rope burning at his neck, was spared at the last minute - "miracle" being his answer for how it happened. He drew from his faith because he seemed to be at a loss in understanding how the hateful energy dissipated from the crowd before they could pull him up among the "strange fruit" that were his former friends.

That picture - featuring a man pointing proudly to the lifeless forms hanging high from a "death tree" - is among the more familiar photos of this grim genre. It would be a ghoulish fool’s errand to rate these photos on a scale of horror. But Minnesota’s place in this macabre pantheon is secure with the photo of the lynching of three young African Americans in Duluth on June 15, 1920. The story was courageously collected and compellingly written into one of Minnesota’s most important historical accounts, Michael Fedo’s book The Lynchings in Duluth.

Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie were touring the northland as roustabouts with a circus that made a stop in Duluth, just up from the Lake Superior harbor. A false claim of the rape of a white woman led to their brief imprisonment, followed by a terrifying siege on the jailhouse. In a bit of irony, the police in the besieged Duluth jailhouse made some attempt to stop the lynching: 100 years later, they were the perpetrators in Minneapolis. The police in 1920 tried, that is, until the commissioner of public safety was said to have pulled them back with the order, “I don’t want to see the blood of a single white man shed for these niggers.”

Designer Denise Fick created a foreboding animation for TPT's North Star.

A handful of whites tried to stop what was coming, but they were no match for the thousands who roared their approval. And the grisly beating, mutilation and lynching of the three young men was played out under the glare of street lights in downtown Duluth 100 years ago this June.

That lynching image is now an American grotesque: a crime captured in a photo as horrific as it is clear, well composed and well exposed. It is an image that leaves a viewer confounded at how there can be both smiling faces and lifeless faces bent from distended necks within just feet of each other. Captured in the manner of a hunting photo, the focus seems to be as much about the killers as it is their prey. But the young, torn bodies of Elias, Elmer and Isaac strike me as profoundly sad, not scary. The fear from this photo comes from looking at the white faces and those expressions that range from apathy to glee to set-jawed hate. And know that this composition is a close-up of the mob: Multiply these faces by the thousands.

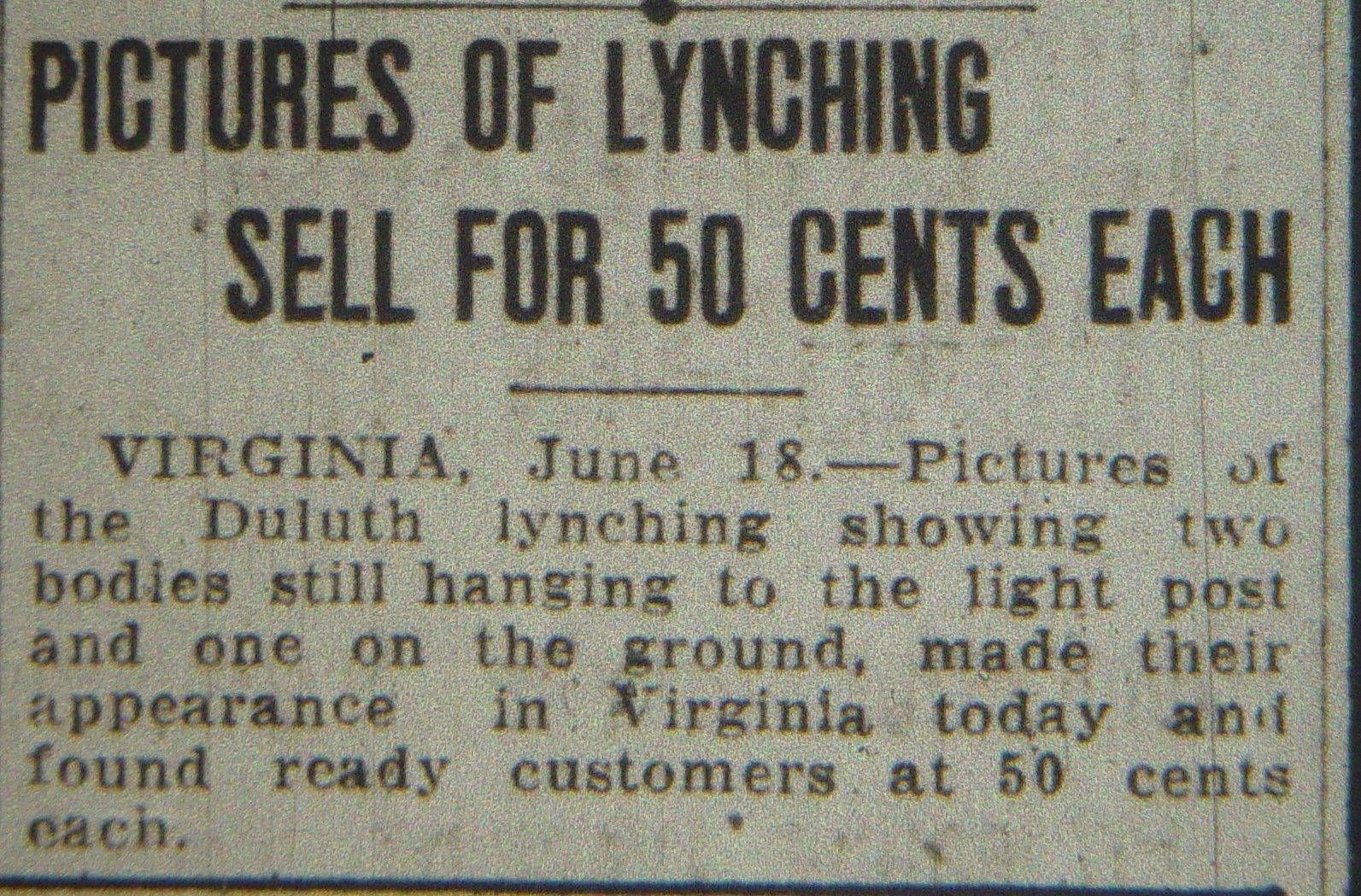

In the grim social network of its day, the photo of the Duluth lynching was bought, sold and saved by many. This was common in the American lynching ethos because body parts - an even greater prize - were harder to come by.

The reprinted photos from 1920 spread between white hands, were kept in dresser drawers and whispered about down the generations in the Zenith City. In the ongoing use of the Duluth lynching photo, even here, there is a risk of disrespecting, dishonoring and revictimizing Elias, Elmer and Isaac. Some might caution that the photo’s use is offensive. Of course the photo is offensive, as was their murder.

So look at it.

And if you haven’t, look at Darnella Frazier’s heartbreaking, heart-stopping, unflinching footage of George Floyd’s police killing a century later. The unwavering bystander's video spread through social media and mainstream media, alike, and it was the key factor in the historic, rapid firing and filing of charges for the four cops involved in George Floyd's death.

In the 1990s, a multicultural group of activists who took the name of the victims of the lynching launched a gradual redemption movement. The Clayton Jackson McGhie Committee began to raise awareness of the history and to build community - and all the while they had to fight against the ongoing racism and resistance to the painful truth of the city’s past. The ambitious idea of a grand memorial became their focus. The drive to remember the three men and offer a place of reconciliation in the place of darkness drove CJM Committee co-founder Heidi Bakk-Hansen who asserted, "I wanna take back that corner" for the three victims and for the city.

In 2003, after years of this reconciliation and engagement work, the CJM committee and a righteous mob of thousands dedicated the stunning memorial to the victims in the same location as the lynching. The downtown spot was an intersection of white supremacist violence and dehumanization; now it has become a crossroads of memory, humanity, ongoing struggle and hope.

The three life-sized reliefs representing the young men breathe life back into them and take energy away from the lynching photo's eternal savagery of their bodies.

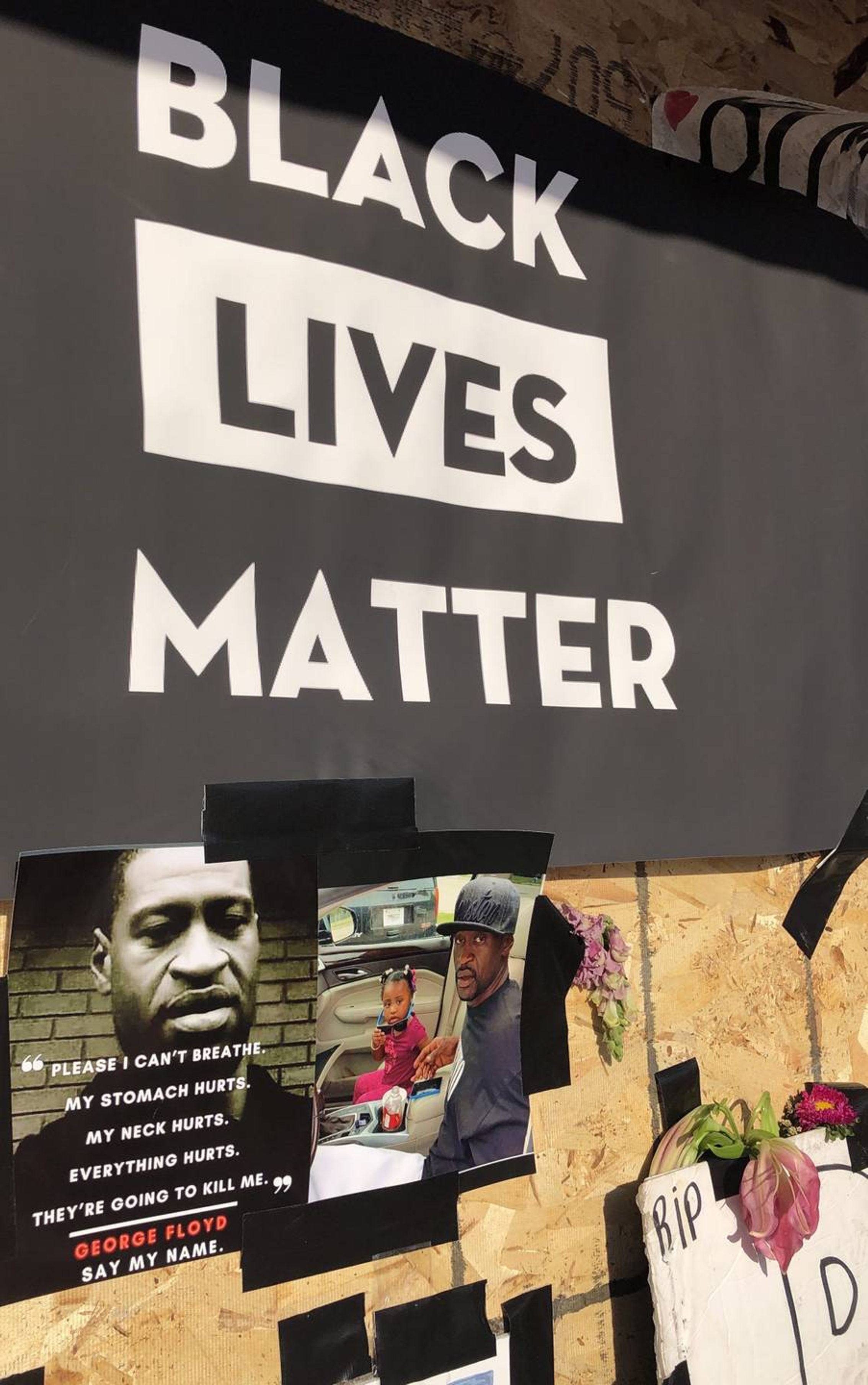

One hundred years after the lynching, Duluthians are gathering at the memorial to mourn George Floyd under the eternal gaze of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie. One hundred and twenty miles south of the historic north-shore intersection, an organic multimedia memorial is growing out of the South Minneapolis intersection where George Floyd was killed by police.

The historic Black district’s artistic, faith-based, entrepreneurial and activist roots are part of why the craggy pavement and surrounding structures are morphing into sacred space, a gathering place and common ground.

The outpouring of art, extemporaneous portraits and protest, and communion have channeled love, fear and outrage. It’s bittersweet that, unlike the word-embossed walls of concrete and life-sized sculptures of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie in Duluth, the flowers, chalk art, teddy bears, giant dream catcher, bus stop decor and other ethereal expressions in the space are not going to last as long as the ageless bronze reliefs up north. There is the semi-permanent mural on the side of Cup Foods - and perhaps there will be a permanent memorial to George Floyd on that spot. Maybe, as some have called for, Chicago Avenue might take his name in memory. Most hopefully – and largely due to the video captured and shared around the world - his ultimate memorial will be real, lasting and just change to a broken, brutal system seen in these images that bookend a century.

Study Civil War-era history for any length of time and you start to realize that it’s seldom as straightforward as some textbooks might have you believe. In North Star: Minnesota’s Black Pioneers, two contradictions exist side-by-side – in the same film, the same state, at roughly the same time: one is a document believed to be the first essay penned by a Black pioneer during the state's territorial days, while the other is a confederate battle flag.

Along with other urban centers across the country, the Twin Cities have a history of racially discriminatory housing covenants that prevented people of color from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. That history ripples in the present-day affordable housing crisis: By limiting opportunities for home ownership, people of color were stripped of one key way to build equity over time. Discover more in “Mapping the Roots of Housing Disparities in Minneapolis.”

Following the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014, Rose McGie was inspired to bake 30 sweet potato pies, which she drove from Minnesota to Missouri in an effort to comfort the community. When George Floyd was killed over Memorial Day weekend in 2020, she took her pies to a reeling community a little closer to home. Find out what has inspired her to bake thousands of pies since 2014.